Federal workers are lining up outside food banks. Disappearing SNAP benefits could cause millions of their neighbors to go hungry, too. 22 states—including MAGA-friendly Iowa, Mississippi, and West Virginia—may already be in a recession. Hiring is down. Inflation is up. Groceries keep getting more expensive.

Americans, in other words, are struggling. And where is President America First?

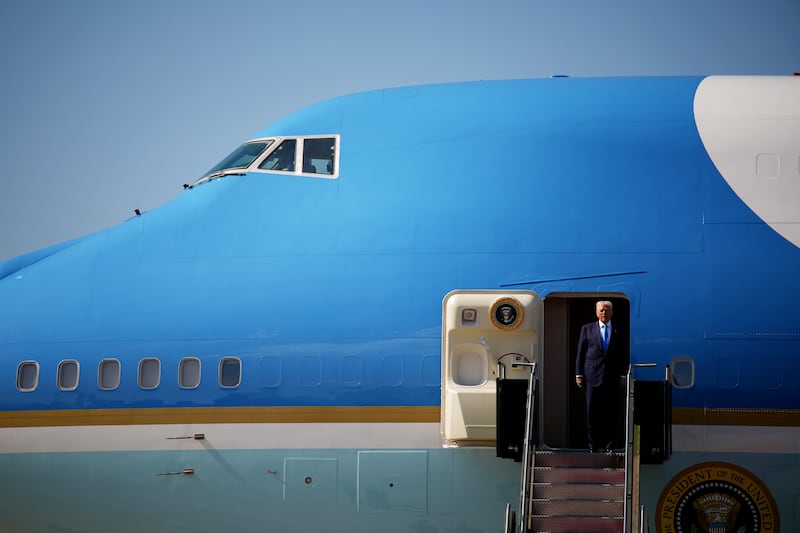

In Asia, of course.

Now, President Trump hasn’t entirely ignored domestic policy over the past several weeks. Someone has to be there to say yes to Stephen Miller, and besides, the East Wing wasn’t going to demolish itself. But to an extent almost no one would have guessed a year ago, Trump, his ratings sagging at home, appears obsessed with winning the world’s approval.

Trump is bringing his signature no-one-tell-Grandpa-what-it-looks-like-he’s-doing dance to Malaysia. He’s calling for everyone to buy Japanese Toyotas, touting a $10 billion investment from the auto company into U.S. plants that is, in reality, far less than meets the eye. He’s bailing out right-wing allies in Argentina with taxpayer dollars. He’s flying to Egypt to negotiate a real estate deal on the sidelines of his ceasefire celebration. Through it all—and even as he gears up for a regime-change war in Venezuela—he’s angling for a Nobel Peace Prize with a PR blitz that puts even the thirstiest Oscar campaign to shame.

It’s a twist neither the president’s MAGA-iest allies or staunchest opponents saw coming. In his dotage, Donald Trump has become a globalist.

To be clear: I’m not an international relations expert. But neither are the vast majority of American voters. And we didn’t need to be experts to know that, for most of his decade-long political career, Trump has been the most prominent isolationist in modern history.

This “America First” rhetoric was the subject of bipartisan scorn in foreign-policy circles. But it was better politics than the establishment realized. According to one pre-election survey, support for America playing an active role in world affairs hit a record low last year. 57 percent of Republicans, and 54 percent of independents, believed the United States should pull back from commitments abroad and focus more resources at home instead. Only 17 percent of Americans agreed that the United States had a responsibility to lead internationally.

Trump wasn’t among them. From the beginning, he offered a dog-eat-dog view of the world, and of America’s role within it. He didn’t promise to stop conducting foreign policy altogether. But where previous administrations, of both parties, believed in forging lasting alliances rooted in shared interests and values, Trump told us the goal was squeezing the maximum amount of short-term benefit for Americans out of every international interaction.

In Trump’s first term, America pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Paris Climate Accords, the World Health Organization, UNESCO and the Iran Nuclear Deal—and that’s just a partial list. In his second, Trump axed USAID and its lifesaving work, stopped calling out countries with rigged elections and turned many of America’s closest allies into counterparties, eschewing shared values in favor of maximum dealmaking leverage.

But in between threatening to invade Denmark, planning military strikes inside Mexico, and enraging millions of Canadians once thought to be un-enrageable with talk of “the 51st state,” Trump has, late in life, become a citizen of the world.

Most presidents start to think about their global legacies after winning a second term. Surprisingly, given his lack of respect for most other norms, Trump is no exception. While it’s hard to keep count of the number of wars he claims to have ended, one thing is clear: the quickest way to curry favor with the United States is by staging a peace accord with its president. In other cases, such as trade with China, Trump seems to be instigating a crisis, then claiming credit when things go back to the way they were before he messed them up.

Even more surprising, given his lifelong relationship history, is Trump’s sudden interest in alliances. The allies are different. The shared values are different. But the principle—that America should stand by its friends even when it’s not in Americans’ short-term interest—will be familiar to anyone who’s ever heard MAGA criticize it.

This new globalism was on full display last Tuesday, when the president welcomed Argentina’s president, Javier Milei, and announced a $20 billion economic bailout financed with American taxpayer dollars. Trump has clear affection for Milei, a conservative firebrand he called “MAGA all the way.” But when asked how offering a giant loan to Argentina would benefit the American people, Trump confirmed that it wouldn’t.

“We don’t have to do it,” he told reporters. “It’s not going to make a difference for our country.”

While the answer was impressively candid, it was hard to describe the logic as “America First.” Ditto the administration’s 50 percent tariff on Brazil, imposed because the country refused to drop criminal charges against a Trump political ally, which raises prices for American consumers. Or JD Vance’s decision to play MAGA Johnny Appleseed, meeting with leaders of right-wing minority parties from Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom—in some cases while snubbing those countries’ actual leaders.

American taxpayers are, both directly and indirectly, funding Trumpism’s global push.

In other cases, Trump is benefiting personally from his choice of allies. The United Arab Emirates invested $2 billion in his crypto company. Not long after, and despite serious national-security concerns, the White House allowed the UAE to buy American-made AI chips. Just two weeks ago, Pentagon Secretary Pete Hegseth announced that Qatar will be allowed to build a military facility in Idaho. Is this because they’re a good ally? Because they helped negotiate an Israel-Gaza ceasefire? Or because they gave our president a $400 million plane for his private use?

It’s impossible to say—and that’s probably the point.

To most voters, these things probably look like corruption. But Trump himself might not see it that way. His policymaking is often described as “transactional.” If a CEO closes a deal, he can expect a big bonus. Why, he seems to be suggesting, should things be any different for presidents?

In other words, Trumpism doesn’t mean the end of a rules-based international order. It’s the beginning, rather, of a new order based on a new set of rules: first, that the American people will readily sacrifice their own prosperity and security to help their president’s friends; and second, that when America gets a win on the world stage, the president and his family should personally benefit.

It’s always possible that the commander-in-chief will sell Trump Globalism more successfully than he sold, say, Trump steaks or Trump vodka. But I wouldn’t bet on it. More likely, in overreaching, he will give his opponents a second chance to reclaim the mantle of national interest.

They should take that chance. Not just to defend old institutions, but to tell a new story about America’s place in the world. Not too long ago, the political establishment failed to convincingly make this point, using language untethered from Americans’ well-being and appearing out of touch with day-to-day concerns.

Trump taught them, the hard way, how risky it is to allow your opponents to claim they’re putting Americans first while you ignore them.

That’s a lesson Trump himself may be about to learn.

The post Opinion: Does Trump, 79, Even Realize He’s a Big Ol’ Globalist These Days? appeared first on The Daily Beast.