In Iowa, a retired math teacher clicked a link in a text message and donated $35. A school secretary in Las Vegas pitched in $50. An interior designer in Pennsylvania, an insurance agent in Chicago and a ski instructor in New Hampshire each gave $100.

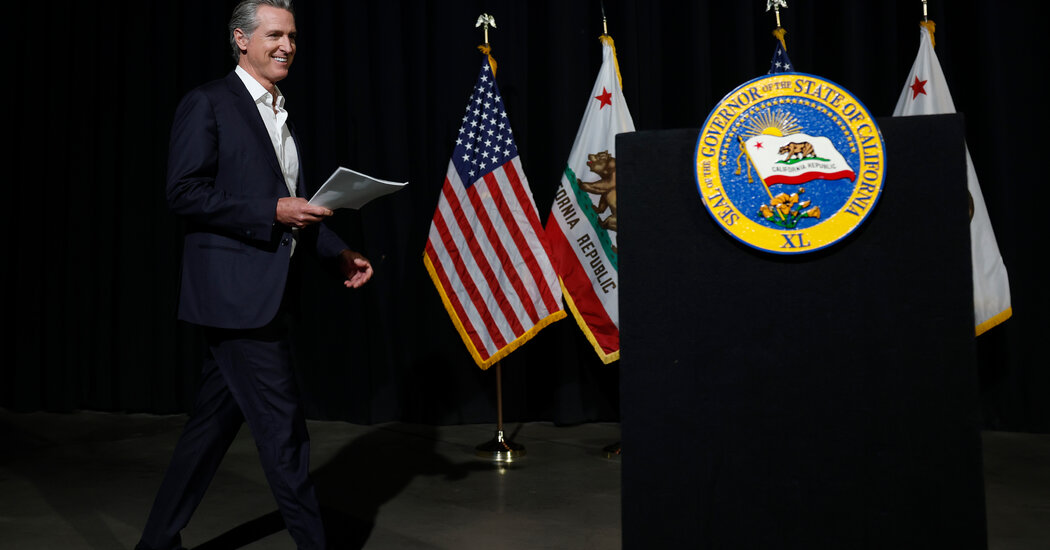

Their small donations all went to California to help Gov. Gavin Newsom try to flip five congressional seats for Democrats.

“I’m so disenchanted with the direction of this country today that I have to support the people that are standing up for democracy,” said Amy Kaufman, the ski instructor. “And Gavin Newsom is one of them.”

Responding to email and text message appeals, small donors from across the country gave Mr. Newsom a combined $38 million for a ballot measure intended to stop President Trump and Republicans from retaining complete control of the federal government in 2026.

Nearly half of donors who cumulatively gave at least $100 came from outside of California. In multiple interviews, these donors said they gave to Mr. Newsom because they saw him as one of the few Democrats fighting Republicans on their own terms. After President Trump asked leaders in Texas and other red states to pursue rare, mid-decade gerrymandering to offset potential midterm losses for Republicans, California is the closest of any Democrat-led state to striking back so far.

Polls suggest that California voters are very likely to pass Mr. Newsom’s redistricting measure on Tuesday, a win that could serve as the ultimate foundation for a 2028 presidential run that he is considering. If he runs, he could tell voters that he directly fought back against Mr. Trump in the midterms.

And he would emerge with a national list of donors and supporters that few other Democratic hopefuls have at the moment.

The list began more than 25 years ago, when Mr. Newsom was a wine entrepreneur just getting his footing as a politician. Mr. Newsom said in an interview that he started building an email list of donors when he was on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and wanted to gather support for a bond measure to fund parks.

“I started going, ‘Oh, emails, that’s interesting and novel,” he recalled. “‘I should use these.’”

From there, he took a methodical approach to building his list, gathering more names and emails every time he ran for another office or put an initiative on the ballot. The list includes names that Mr. Newsom has collected organically, as well as those in databases he has purchased.

The project accelerated in 2021 when Republicans tried to recall Mr. Newsom and he reached out to Democrats across the country for support. Then, in 2023, Mr. Newsom created a political action committee to support Democrats in Republican-controlled states — giving him a reason to collect more names and emails from beyond California.

Building the list had become a discipline. Mr. Newsom called the list “huge” but declined to say an exact number. He now calls the list “the most valuable asset” of his political career.

“It’s a very deliberative investment,” Mr. Newsom said. “It’s a lot of resources. It’s a lot of time and a lot of iteration.”

Along the way, Mr. Newsom picked up contact info for Steven Lamansky, a retired high school math teacher in Ankeny, Iowa, just north of Des Moines. Mr. Lamansky sent his first $35 donation to the Proposition 50 campaign on Aug. 10 after receiving a text message pitch from Mr. Newsom’s campaign. Two weeks later, he sent another $35. The next month, $35 more.

Mr. Lamansky, 77, said he donated because he wanted to counter gerrymandering in Republican-led states and help Democrats to take back the House next year. But he also pitched in specifically to boost Mr. Newsom.

“I find him a very dynamic person,” Mr. Lamansky said. “Every time I’ve heard him on different shows, he’s really got his ducks in a row. He knows his facts. I really like him, and I’d like to see him run for president.”

Mr. Newsom has curated his national image, just as he has his supporter list. He has gone on Fox News to attack Republicans, including a face-off with Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida in 2023 that was billed as “The Great Red vs. Blue State Debate.” He started the podcast “This Is Gavin Newsom” this year, turning heads when he asked conservatives like Charlie Kirk and Steve Bannon why the Democrats failed in 2024.

After Mr. Trump sent National Guard troops to Southern California in June during immigration raids and protests, Mr. Newsom returned to his place as a chief antagonist of the Republican president. One night, with troops in Los Angeles, he gave a speech on national television warning Americans that “democracy is under assault right before our eyes.”

This summer, Mr. Newsom used a more experimental communication strategy. With help from his young staff, Mr. Newsom adopted an aggressively satirical voice mocking Mr. Trump on social media. And he began appearing on platforms that cater to young, male audiences — a cohort that Democrats lost ground with in last year’s election.

Between banter about sports and video games, the governor has slipped in pleas for his redistricting measure into the “All the Smoke” podcast, which is hosted by two retired N.B.A. players, and a livestreamed game of Fortnite with a Twitch streamer known as ConnorEatsPants.

Republicans have struggled to counter Mr. Newsom on Proposition 50, in part because of the governor’s fund-raising prowess, but also because he was so effective in making the race a referendum on Mr. Trump in a Democratic state. They lacked a central figure or message around which to build a groundswell of opposition.

Representative Kevin Kiley, a California Republican who would become immediately vulnerable if Proposition 50 passes, has spent years challenging Mr. Newsom, including during the 2023 recall when he ran as a candidate for governor.

Mr. Kiley has been a lonely voice in Washington calling for a national prohibition on mid-decade redistricting. He said the ballot measure seemed to be serving as a “launching pad” for Mr. Newsom’s 2028 aspirations.

“His entire governorship,” Mr. Kiley said, “he has treated as a warm-up to running for president.”

Mr. Newsom’s efforts have resonated with Democratic voters beyond California, as he has climbed to the top of several Democratic presidential primary polls in the months since he began the redistricting campaign.

It is, of course, too early to anoint any contender, let alone Mr. Newsom. The California governor could struggle in many states to overcome his reputation as a liberal coastal elite, an image that Democrats are desperately trying to shed at the moment.

Though Mr. Newsom is getting a lot of traction with the Democratic activist base, it does not mean he will win a primary three years from now, said Mike Murphy, a former adviser to Republican presidential candidates who supported Joseph R. Biden Jr. in 2020 and Kamala Harris last year instead of Mr. Trump.

“He’s got a flashy thing of the moment,” Mr. Murphy said. “In the 100 steps to the nomination, it doesn’t hurt him. I just think you can overrate it.”

Matt Bennett, a Democratic strategist who worked on campaigns for former President Bill Clinton, said that Mr. Newsom may also have a hard time running a presidential campaign because of a perception nationally that California is a troubled state.

“What he can do is run on his aggressive efforts to take on Trump and MAGA in various ways,” Mr. Bennett said, adding that the redistricting measure would be “the most important and prominent of them.”

Steven Rich contributed data analysis, and Shane Goldmacher contributed reporting.

Laurel Rosenhall is a Sacramento-based reporter covering California politics and government for The Times.

The post Newsom Turns a California Election Into a National Platform appeared first on New York Times.