Republicans have a net-zero goal they can finally get behind: not for carbon emissions but for immigration. And they may achieve it as soon as this year. In a July white paper, three economists projected that, in a remarkable departure from decades-long patterns, more foreign-born people will likely leave the United States in 2025 than will enter. In the three months since, the Trump administration’s aggressive actions have driven net migration even lower than expected, one of the authors, Wendy Edelberg of the Brookings Institution, told me. Student-visa numbers are lower than previously anticipated. In September, the Department of Homeland Security boasted that since President Donald Trump’s return to office, it had deported 400,000 people, more than triple the pace of deportations under the Biden administration; it has billions more to spend on further enforcement efforts, courtesy of Congress and the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. An unknown number of people have voluntarily left the country rather than be forced out.

We will not know with certainty for some time whether America has hit net zero, but the White House is already claiming victory. “Promises Made. Promises Kept. NEGATIVE NET MIGRATION for the First Time in 50 Years!” Trump declared on Truth Social in August. Prompted by a CNN report, that claim could, if anything, prove to be too restrained. If the United States experiences negative migration in 2025 and, as seems likely, 2026, it will probably be the first net outflow in nearly a century.

To “America First” true believers, the recent trend heralds a return to a halcyon era. “Finically [sic], culturally, militarily—immigration was net negative. All population growth was from family formation,” Stephen Miller, Trump’s deputy chief of staff, wrote on X in August. The best data we have, derived from the decennial census, suggest that Miller was incorrect. In the buoyant decades after World War II, net migration was low compared with the Ellis Island era of the early 20th century, but still positive. According to census data, the only decade in American history when migration was net negative was the 1930s—during the Great Depression.

For the past decade, nativism has proved politically potent enough to carry Trump to the Oval Office twice. It may be powerful enough to bring net migration down to zero, perhaps for some time. If that happens, the America that emerges will be reduced, not just by lower economic growth but also by a shrinking population. The notion that this would at least leave native-born Americans better off is also far-fetched. We know because the United States has tried it before.

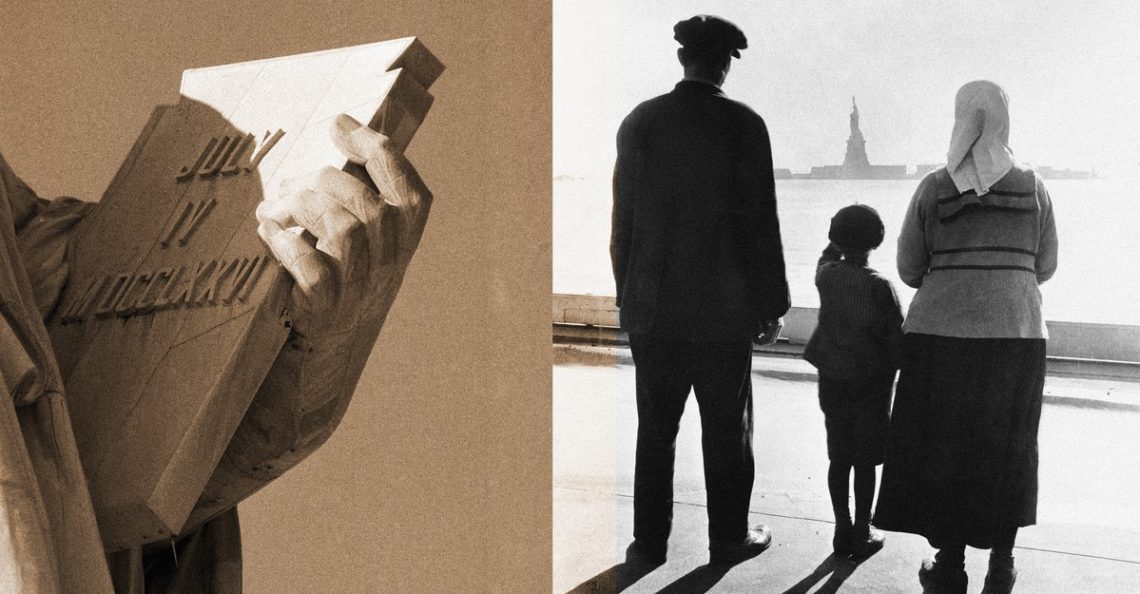

American history has featured prior bouts of nativism. Many of the animating grievances are unchanged. In 1921, Calvin Coolidge, the vice president–elect, wrote an article in Good Housekeeping titled “Whose Country Is This?” At the time, the share of Americans born overseas was 13 percent, close to the historical maximum. There was intense worry about the scourge of migrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. “Our country must cease to be regarded as a dumping ground,” Coolidge wrote. He warned not just of moral and cultural degradation but also of economic peril: “The unassimilated alien child menaces our children, as the alien industrial worker, who has destruction rather than production in mind, menaces our industry.” Subtract the explicit eugenics and simplify the diction, and Coolidge’s arguments resemble Trump’s warnings.

When Warren Harding died of a heart attack, in 1923, Coolidge ascended to the presidency. “America must be kept American,” he said in his first address to Congress. The following year, he signed the Johnson-Reed Act, which ended the country’s open-immigration era. Strict quotas were imposed. Northern European countries were given priority, and migrants from Asia and Africa were effectively banned. These harsh limits remained in effect for 40 years.

Hostility toward immigration in American history follows a rough cycle: It increases in proportion to the foreign-born share of the population and the sense of economic precarity among the native-born. Then it relaxes as restrictions come into effect, some migrants return to their home countries, and the descendants of those who remain assimilate into the body politic.

This historical cycle doesn’t just offer an abstract guide to the future; it also gives empirical evidence for whether native workers have really benefited from reductions in migration. During the Great Depression, Mexican workers, who filled undesirable jobs on farms, in meatpacking plants, and on railroads, were blamed for immiserating hard-strapped American citizens. Officials took action: More than 400,000 workers of Mexican descent (some of them American citizens) were removed or cajoled into self-deporting. But when the economists Jongkwan Lee, Giovanni Peri, and Vasil Yasenov examined the lingering consequences, they found that places with higher rates of Mexican repatriation had worse outcomes for left-behind natives—who had both slightly lower rates of employment and lower wages. In the 1960s, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations phased out the Bracero Program, which had allowed millions of seasonal Mexican workers to enter the United States to work on farms. An influential study of the policy’s effects published in the American Economic Review similarly found that the program’s demise did not meaningfully increase wages and employment for native workers. Farms instead reacted by adopting mechanized techniques where they could.

Studies also find similar effects for past drives to remove undocumented immigrants—the aim of the current administration. In 2008, the Department of Homeland Security launched a program known as Secure Communities, which aimed to check the immigration status of everyone arrested in the country. The program went into effect gradually over the course of four years, allowing economists to discern what happened to local labor markets because of deportations. A study in the Journal of Labor Economics, published in 2023, found that the number of undocumented workers had decreased, as intended by policy makers. But the employment effects were the opposite of desirable: The program led to a slight increase in joblessness rates for male citizens and no improvement in wages. Another study of the Secure Communities program found that the removal of undocumented workers led to a long-lasting decline in construction employment. The result was less home building and, according to the authors, higher house prices.

These findings might seem paradoxical. When you remove laborers, wages ought to rise as employers compete for remaining workers, if other things remain equal. But other things do not remain equal. “There’s a cartoon economy in the minds of several people in the White House in which business activity in the United States remains constant even when 1 million people per year are forcibly removed from that economy,” Michael Clemens, an economist at George Mason University, told me. In farming, manufacturing, and many other capital-intensive industries, employers can invest in equipment instead of hiring more native-born workers. When wages rise, some prospective entrepreneurs are deterred by increased costs and choose not to start new businesses.

These disruptions will ripple through the broader economy. Low-skilled workers are complementary to better-remunerated high-skilled workers. Think of how a sudden reduction in the supply of nannies would affect white-collar work, or what a dearth of home health aides would do for family finances. By one estimate, the U.S. has 8.3 million undocumented workers. One calculation from the Peterson Institute for International Economics found that if Trump does manage to deport all of them during his second term, he will also zero out all of the economic growth that has been previously projected. For that reason—not to mention the exorbitant cost of such a deportation drive—Trump is unlikely to do so.

The wage effects of the current deportation drive might be the opposite of what immigration restrictionists hope for, but they are also not so negative that Trump and his allies would bear immediate political costs. And even if the overall economic effects are negative, some of the benefits would accrue to one politically important group: working-class, native-born men. (In this way, the policy mirrors the logic of the president’s trade restrictions, which leave the overall economy worse off but benefit narrow favored constituencies.) Native-born men, the theory goes, will be simultaneously pulled into the labor force due to shortages and pushed into it as less generous welfare policies—such as the recently passed work requirements for Medicaid—come into effect. “I always point out: The Japanese eat, right? They pick their crops, and they don’t have millions of low-wage agricultural workers,” Simon Hankinson of the Heritage Foundation told me. “You can say the same with Hungary. It is possible to function as a developed economy without unlimited cheap labor. It’s just harder.”

The example of immigration-averse economies such as Hungary and Japan may be apt in another way: Both are losing population. So will America if migration remains near zero for the next five years. The underlying math is stark. The average fertility rate for U.S.-born women is currently about 1.5 births, well below the replacement rate of 2.1 births per woman. Little evidence suggests that this rate will rise anytime soon. (Foreign-born women in America have a higher birth rate of about 1.8, but even this would lead to population decline over time.) Last month, the Congressional Budget Office released an analysis showing that without migration, the U.S. population will begin shrinking as soon as 2031.

Some think that this impending demographic decline can be reversed through government incentive—Trump has called himself the “fertilization president”—but experiments in natalist policy in other countries have been uniformly disappointing. For years, South Korea has tried to boost its fertility rate by instituting baby bonuses, generous parental leave, and even preferential mortgage rates for families with kids. But the fertility rate, currently at 0.75 births per woman, has remained well below replacement level.

But suppose that America were exceptional enough to develop a natalist policy that works. Even so, it would be at least 16 years before the children of that hypothetical baby boom entered the labor market. The interlude would be painful. The number of native-born American workers in prime age has been stuck since 2013, and it is not expected to start growing.

The United States has always been a nation of expansion: It has never before experienced population shrinkage year after year. If it does, it will be less rich in terms of GDP, because the economy simply shrinks when there are fewer people. Over the long term, there will be less technological and biomedical progress, particularly if the Trump administration successfully limits legal, skilled immigration and browbeats American universities into submission by starving them of science-research funding.

Other problems with a shrinking population would arrive quickly as the finances of entitlement programs become even shakier. The country currently has only 2.7 workers for every Social Security beneficiary, down from 3.4 in 1990. This decline already means that the program is on the path to insolvency. Because benefits exceed the payroll contributions of current workers, the trust fund that covers the shortfall is being depleted. The Social Security Administration estimates that—even with annual net immigration of at least 1.2 million a year—its trust fund will be exhausted by 2033, at which point benefits will be immediately reduced by about 23 percent. With even fewer workers, the day that the U.S. welfare state starts to teeter will move closer.

As much as economists might think that immigration is beneficial, its politics remain treacherous. The Trump administration’s dreams of “America’s next golden age,” wherein lower migration raises wages, lowers unemployment, and reduces crime, seem secondary to concerns about the cultural threat of migration. The paramount issue is the same as it was for Coolidge: “America must be kept American.”

Similar sentiments are observable internationally. Plenty of countries, among them Japan and South Korea, would rather shrink economically and demographically than allow large flows of permanent migrants. A primary motivator for the narrow majority who voted to take the United Kingdom out of the European Union in 2016 was anxiety about migration, especially from new EU member states in the east. Polls from around the time show that many Leave voters saw Brexit as “the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders.”

After Brexit, the Conservative Party tried explicitly to keep net migration, including unauthorized arrivals of people on small boats, below certain numerical targets. Its failure to do so has led to its precipitous unraveling. A rival party on the right, the Reform Party, headed by Nigel Farage, is much more hard-line—it wants to abolish the permanent-legal-residency system (akin to the U.S. ending the green-card program). It is also far ahead of its rivals in the national polls. Almost a decade after Brexit (and its attendant economic harms), polarizing battles over immigration are still not resolved.

There is a real risk that America will become mired in such a lengthy campaign for immigration restriction as well. A small fringe has even imported European-style “blood and soil” arguments to claim that the United States is rightfully reserved for “heritage Americans” or for people of European descent.

Yet what has poisoned the politics of migration for ordinary U.S. citizens, polls indicate, is the suspicion that it has become uncontrolled. On this key point, Trump is correct: The Biden administration oversaw, wittingly or not, an extreme surge in migration. From 2021 to 2024, the number of migrants in the country grew by 6.8 million, mostly unauthorized, accounting for 85 percent of population growth. For scale, this is close to the peak rates of migration to the United States, such as those experienced in the 1840s, when the Irish Potato Famine and European revolutions brought in huge swaths of Irish and German Americans.

The recent influx has pushed the share of foreign-born Americans to 15.8 percent—higher than the levels that preceded Coolidge signing the Johnson-Reed Act, in 1924. In fact, it is the highest level ever recorded in American history. These changes are the result not of deliberate policy debate in Congress but of an inability to cope with millions of migrants claiming asylum as it became clear that this was a path to being released into the interior of the country.

Since the change in administration, though, illegal migration at the southern border has basically stopped. In the six months from February to August of this year, the Border Patrol reported 73,667 migrant encounters on the southern border, just 7 percent of the more than 1 million encounters over the same period in 2024. The Darién Gap, the treacherous rainforest passage between Colombia and Panama once traversed by hundreds of thousands of Central American migrants on their way to the United States, is now seldom traveled.

Although the U.S. economy absorbed the additional unauthorized workers of the Biden years rather well (it may even explain the higher growth rates compared with Europe’s), the border mismanagement was a knockout blow to Kamala Harris. Future Democratic candidates may need to repudiate the Biden-Harris record if they hope to win a general election, but the internal pressures within the party may not allow that. During a 2019 presidential-primary debate for the party’s nomination, the 10 candidates onstage were asked to raise their hand if they’d provide government-run health care to undocumented immigrants. All 10 raised their hands. Such images are not easily forgotten.

Yet the United States needs credible advocates for orderly, controlled migration. If America experiences sustained outflows of migration, it will be in deep trouble. Eliminating current workers does not even present a trade-off between growth and inflation—it is worse for both. The Trump administration’s efforts to narrow paths for legal, higher-skilled migration—by, for example, adding a $100,000 surcharge on the H-1B–visa program—show that its ideal immigration regime is one not of selection but of shrinkage. An optimist might hope that, once some recent migrants leave and others are assimilated into society, the U.S electorate will go back to its welcoming attitude toward immigrants. Perhaps voters will recoil at Trump’s harsh tactics, and the politics of immigration will become more placid. A pessimistic student of history, though, might fret that this is the beginning of another 40-year period—beginning with this presidential term and continuing through a J. D. Vance presidency—in which America’s gates are all but pulled shut.

The post The Year With Net-Zero Immigration appeared first on The Atlantic.