The devil and his minions have haunted me all my life.

As far back as I can remember, I’ve been visited by the unquiet dead, the hungry ghosts, and even Old Scratch himself in my dreams. Perhaps these nighttime visitations were spiritual attacks, perhaps they were the predictable manifestation of the violence and instability of my upbringing.

Like Piper Laurie in ‘Carrie,’ my mother forced me to kneel while she stood above me bellowing. ‘Humble yourself before me!’ she shrieked. ‘GodDAMN you, humble yourself!’

Maybe they were both; maybe the kind of moral derangement that afflicted my parents was a kind of demonic possession.

The devil I know

I’m not sure I believe in God, but I’m getting closer to believing in the devil. That’s a confused position, admittedly, but that’s what you get from a guy who believed as a child until it was punished out of him and then spent too many years as an obnoxious “new atheist” adult.

Whatever the answer may be, I’ve been terrified and fascinated by the supernatural, the uncanny, and the grotesque all my life. The kinds of spooky stories that gripped me were the type you find in Victorian English ghost story anthologies. Authors like E.F. Benson, M.R. James, and Elizabeth Gaskell.

If you like these too, no one reads them better than English podcaster Tony Walker. His “Classic Ghost Stories Podcast” is one of the few I find so good that I voluntarily pay for it. This is no amateur sideshow; Walker’s narration is professional grade. Why he’s not rich reading books for Audible, I’ll never know.

Weeping and wailing women in veils who glide down hallways. Rain-bedraggled brides hitchhiking on the side of the road who disappear from their ride’s passenger seat as he drives past Resurrection Cemetery. Fingerprints that appear on the windows of automobiles that cross the railroad tracks where a locomotive hit a school bus long ago killing the children on board. Their spirit fingers gently push your car along to make sure you don’t meet their sad and untimely fate.

In search of … belief

Like many kids of the 1970s and 1980s, I grew up watching shows like the cryptid/aliens/spook-filled “In Search Of,” narrated by Leonard Nimoy. My library card was full many times over with every book on Bigfoot, extra-sensory perception, telekinesis, poltergeists, and the Bermuda Triangle.

Have you heard about the moving coffins of Barbados? That’s top-quality spine tingles. As the story goes, a wealthy family living on the Caribbean island built a family vault in the cemetery. Every time a member died, the crypt was opened to accept a new coffin. And every time the crypt was opened, the coffins that were already there were tossed about helter-skelter.

Maybe it was flood waters. Except that there was no evidence of water incursion. Maybe pranksters did it. But the family sealed the stone door and sprinkled sand on the floor, and there was never a footprint betraying a (living) human presence.

For a proper classic haunting, you can’t beat the Brown Lady of Raynham Hall. Nearly everyone with a passing familiarity with the spirit world of 20th-century popular culture has seen the photograph of this long dead woman, a translucent, begowned figure descending the grand staircase of the palatial home in Norfolk, England, built during the reign of James I in 1620.

According to two photographers who were documenting the inside of the estate in 1936, as they were setting up a shot, they looked up at the stairs in astonishment. A veiled specter was float-walking silently down the stair treads, and they had just enough time to open the shutter on their plate camera and capture the most famous ghost photograph of all time.

Was she the shade of Lady Dorothy Walpole? Lady Walpole was said to have been immured in a room in Raynham Hall for the rest of her life at the hands of her husband, Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend, who was angered by her unfaithful dalliances.

Or was this just the first and best example of trick-ghost photography, a double-exposed photographic plate? In the early days of photography, the public was not wise to the trickery available to a skilled image-maker. Long before Photoshop and AI, the public believed the camera never lies.

I want to believe. There’s something magnetic, romantic, and almost erotic about the possibility that a curtain separates us from the realm of the dead and that it thins at certain times, like now. As a child, I delighted in being scared so badly I didn’t dare turn off the flashlight under the covers I used for my clandestine and very-much-not-allowed post-bedtime reading.

Joy interrupted

Yet the possibility of an ethereal realm where the dead who refuse to acknowledge their condition “live,” a plane where real devil cavorts are not merely fun and games. If that plane exists, and if it’s populated by any of the henchmen attributed to Satan, then the other side is very serious business indeed. I’m not so sure I want to believe, in that case, but I’m also not so sure that I don’t.

When I was 8 years old, my family took a rare trip to a sit-down restaurant on Christmas Eve. We were poor, and a night out at Demicelli’s Italian Restaurant was so special that Christmas would have been joyful even if we didn’t get a single present. As we walked toward Placentia Boulevard in Fullerton, California, I looked at the night sky and saw the brightest star I’d ever seen.

“Mommy, look!” I said, tugging at my mother’s sleeve. I pulled on her cigarette hand, which annoyed her. “It’s the star of Jesus, Mommy. It’s the star that guided the Wise Men to the baby Jesus!”

It was wondrous. It made me feel light-headed with a joy I’d never felt.

My mother made a derisive sniggering noise as she blew out smoke. “Oh, no it isn’t, Josh,” she mocked. “It’s just a star. Probably Venus.”

My face went red with embarrassment, and I stayed quiet the rest of the night. I felt stupid. Unsophisticated. Dumb. Childlike. Naive. And substandard. This was a problem that repeated itself over the years. My mother was the resentful “victim” type, and she was at war with God.

I convinced her to take us to the Presbyterian church where I’d been (to her reluctance, as she recalled it) baptized as an infant for Christmas Eve services in 1986. Mother spent the walk home railing about those “Goddamned hypocritical Christians! Where were they for this single mother when I needed a little help to put food on the table?”

I can’t repeat the rest of what she said in a respectable publication.

Maternal monster

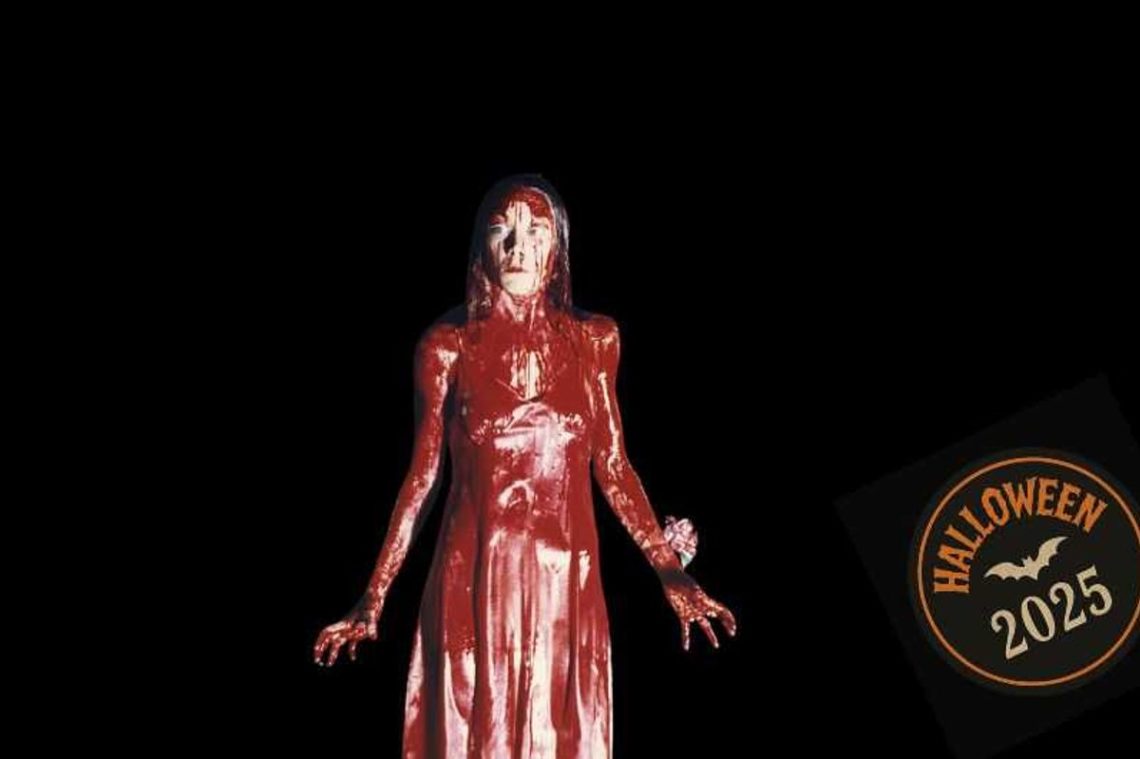

It wasn’t until my 40s that I realized why I had been captivated to the point of obsession with certain dark characters in disturbing films like 1976’s “Carrie.” This was an adaptation of Stephen King’s debut novel of the same name, a book that still ranks among his finest work. It’s only nominally about a teen girl with telekinesis, the psychic ability to move objects with her mind. The story is really about a frightened girl who grew up with a maternal monster.

If you’ve seen the movie, you remember Piper Laurie’s almost kabuki performance as Margaret White, a religious fanatic tormented by her own sense of failure and sin. Seeing herself as a fallen woman who fornicated with a man, she uses extreme interpretations of scripture to berate and subjugate the result of that union, her daughter, Carrie. Just as Margaret believes she can never be forgiven, she can never forgive her daughter for being born, for embodying her mother’s sin in too-real flesh.

So she screams at Carrie, beats her, forces her to confess sins the girl has never committed (they were Margaret’s sins), and worst of all, locks her in a “prayer closet.” The scene that terrified me the most was the vignette in the dining room when Margaret forces Carrie to her knees as she intones about how God had loosed the raven on the world, and the raven was called sin.

“Say it, woman! Say it!” Margaret screams. “Eve was weak. Eve was weak!”

She drags Carrie to the prayer closet, a black cloak whirling about her like the wings of the raven, and babbles insanely while her daughter screams for mercy. Lighting a candle in the dark, Carrie looks up to a figure of St. Sebastian on the wall, a grotesque effigy with agonized eyes reflecting the pain of his arrow wounds.

Fascinated by fear

Margaret White obviously had a severe condition called Borderline Personality Disorder, which also afflicted my mother. While my mother was not a religious fanatic, she treated me the way Margaret White treats Carrie. Just as in the movie’s dining room scene, my mother forced me to kneel while she stood above me bellowing. “Humble yourself before me!” she shrieked. “GodDAMN you, humble yourself!”

My mother did not want what she claimed she wanted: respect and filial piety. She wanted to be worshiped. My mother created herself God in her own image.

So I prayed to God to be delivered from my mother’s prison, but I never got an answer, or one I recognized. I was more certain that the world was full of angry entities, though, and to say I felt haunted wouldn’t go far enough.

That which terrorizes also fascinates. Over my life, I’ve tasted and re-tasted the fear through movies like “Carrie” and “Mommie Dearest.” Fictional versions of my real-life horror were a poison candy; they hurt so good, like the compulsion to thrust the tongue repeatedly into a canker sore that won’t heal.

I still don’t know what I believe about God, the soul, heaven, or hell.

I knew what I saw

No Halloween story would be complete without a personal anecdote of an encounter with the unexplained. This is the first time I’ve told this story to anyone, let alone in print. Like I do myself, you may doubt me. I admit that I was halfway to drunk when it happened. But in the moment, I knew what I saw and heard, I knew I was only buzzed on three beers, not falling-down drunk. I wasn’t hallucinating pink elephants or anything else.

It was 1992. I was 18 years old and sharing an apartment with my best friend, Lisa. It was movie night in the living room, and it was my turn to fetch fresh Molson Goldens from the refrigerator. I put the sweating bottles on a round cocktail tray with a rubber no-slip bottom I’d brought home from the restaurant I worked at.

I was a skilled waiter who could hold a tray with four entrees and several cocktails without spilling. And though I’d had a few beers, I was not drunk. In the hallway as I was about to enter the living room, one of the standing beer bottles on the tray violently flipped over to the horizontal with a thud. It wasn’t the kind of soft thud that happens when something tips over. It was a THUD, as if someone had thrown the bottle into the tray.

Remember, it was a rubberized tray. It was actually difficult for a glass on such a tray to slide, let alone tip over. I had not tilted the tray; I was not weaving drunkenly as I walked. The other beer bottle didn’t tip over. The two mugs on the same tray didn’t move. More, the same thing happened a few minutes later in the living room. My (replaced) beer bottle on the side table, three feet from reach, loudly tipped over on a perfectly level table and made a loud rap.

I remember so clearly stopping still as the blood drained from my head. Did I really just see what I thought I saw? I did. And I felt it, too.

In that moment in the hall, I said this in my head: “What you just saw and heard really happened. You’re not drunk, and you’re not hallucinating. But no one will believe you, and over time, you will not believe you either. Your memory will soften, and you will convince yourself that you were drunk and that you somehow caused these bottles to tip over in apparent defiance of the laws of physics and friction.”

That’s exactly what happened. As I tell you this story, I doubt myself. At the same time, I remember the warning I spoke to myself in my head about doubt there, in the moment, and I know I wasn’t crazy.

Happy Halloween.

The post ‘Carrie’ and the monster who raised me appeared first on TheBlaze.