Since U.S. President Donald Trump returned to office in January, there has been no shortage of liberal internationalists mourning the downfall of U.S. soft power. Trump’s moves to pull back from the United Nations, ravage foreign aid, and mute the Voice of America have dismantled the government’s soft power tool set, while his often derisive and self-interested approach to global engagement—coupled with rapid democratic decay at home—have dimmed the United States’ glow in the eyes of the world.

But as Americans eulogize soft power, they should push past nostalgia to consider what precisely has been lost. Although opinion surveys show that Washington’s global reputation has indeed suffered since Trump’s second term began, the connection between this downturn and the mothballing of soft power instruments is less clear.

Joseph S. Nye, who coined “soft power” in Foreign Policy in 1990, defined it as “the ability to affect others and obtain preferred outcomes by attraction.” Over time, as the concept was embraced by policymakers and analysts, it grew into an amorphous umbrella term for a wide array of policies, programs, and expenditures. These came to include a country’s alliances, international broadcast capabilities, participation in global institutions, development aid, advancement of science, support for universities, diplomacy, funding for think tanks, academic exchange programs, and tariff policies. Outside the realm of government, soft power is also used to refer to global sporting activities, tourism, business, and cultural influence.

Not all of these have equal value as diplomatic tools, nor have they necessarily deserved decades-long government support. Even ardent defenders of defunct programs and institutions, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), acknowledge that decades of bureaucratic inertia and mission drift had made them less effective.

The constellation of soft power projects that existed at the end of U.S. President Joe Biden’s term will not return in its prior form—nor should it. Those who believe in the potency of soft power need to begin reckoning with that reality now in order to begin to reimagine the field for the future.

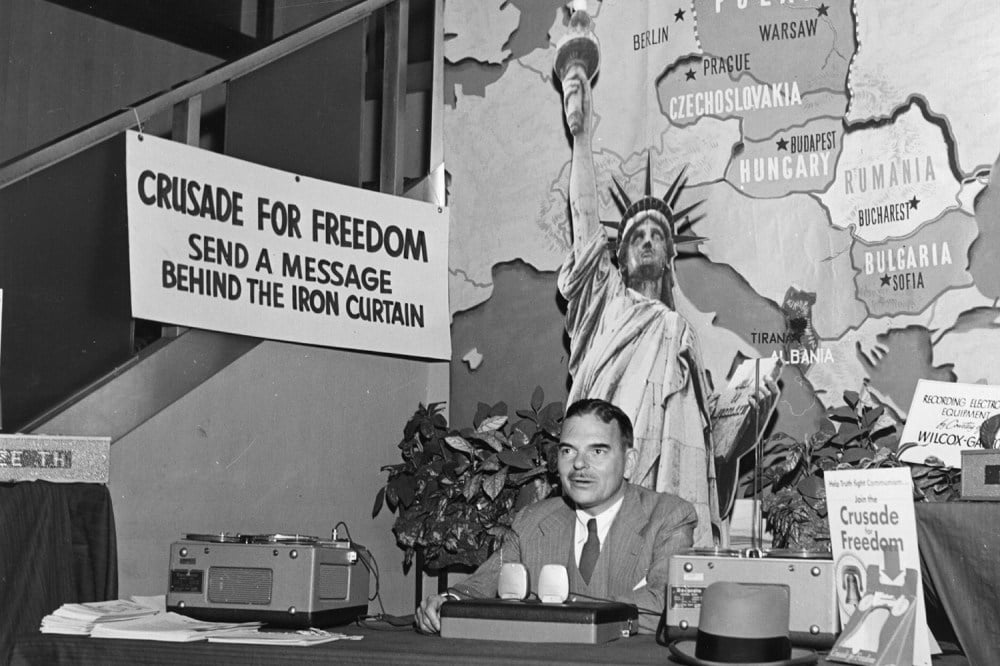

The idea of investing in programs to promote goodwill toward the United States dates back to the Cold War with the founding of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in 1950, the U.S. Information Agency in 1953, USAID and the Peace Corps in 1961, and the National Endowment for Democracy in 1983. (Voice of America, or VOA, was created earlier but expanded significantly during the Cold War.)

With passage of the 1961 Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act, the State Department also funded cultural outreach projects, which included creating U.S. libraries abroad and sending jazz musicians on global tours. Efforts to counter Soviet influence, promote liberal values, and win friends around the world were widely seen in Washington as vital investments.

This visionary Cold War push reflected the United States’ self-image as a nation astride the globe. That boundless sense of enlightened self-interest, encompassing the fate of liberal values and ordinary people everywhere, was inspiring but also unsustainable.

As the Cold War slipped into the rearview mirror, the rationale for these programs grew fuzzier. When the Clinton administration folded the U.S. Information Agency—charged with “telling America’s story to the world”—into the State Department in 1999, it was a sign that times had changed and that waging a public relations offensive on behalf of the United States no longer seemed essential. Still, many other soft power institutions endured or even grew, adopting missions, including democracy promotion and economic development, that were less clearly grounded in U.S. national security interests.

Proponents of soft power rightly point out that these programs account for a minuscule fraction of U.S. overseas spending. But they still required tens of billions of dollars in annual investment, even as solid markers of progress were sometimes elusive. Global freedom has been sliding for 18 years straight as political rights and civil liberties have deteriorated, according to Freedom House. In nearly every year since the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the majority of Americans polled by Gallup have said they are dissatisfied with the United States’ role in the world. While the situation might be even worse without U.S. expenditures, this record hardly makes a clear case for continuing to invest in the same soft power programs.

The blending together of widely varying activities under common headings has compounded the problem. For instance, the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which supervises VOA, has suffered from a split personality, functioning partly like a U.S. version of the BBC seeking to project credible journalism worldwide, partly as an information lifeline for closed societies, and partly as counterprogramming to Russian and Chinese disinformation. The tension among these ambitious but distinct objectives rendered the agency less effective than it should have been, even far before Trump set out to dismantle it this year.

USAID’s activities also spanned the gamut, with the agency lumping together programs that served manifestly vital U.S. interests with those that did not. Since its founding, USAID tussled with the State Department, as its leaders often sought to promote development aid as an independent moral imperative rather than as an instrument serving other goals.

In 2023, around $16 billion of USAID spending went to Ukraine. This funding was not meant to promote Washington’s appeal but to fortify an ally in an existential war through direct support for the government that would fund repairs after Russia’s attacks on the power grid and other essential lifelines. But for many programs—such as those highlighted by the agency’s Republican antagonists, including support for circumcision in Mozambique and diversity, equity, and inclusion in Myanmar—the connections to U.S. interests were less obvious, to say the least.

Over time, partisan fights in Congress and proposed legislation to scale back USAID laid bare a political foundation too thin and weathered to support the hefty programs on which lives depended. Decrees and reorganizations gradually tightened the State Department’s control, with the absorption of USAID by the department earlier this year marking a final step in this progression.

For Trump lieutenants such as Russell Vought and Vice President J.D. Vance, soft power agencies such as USAID were part of a nefarious deep state, corrupted by progressive values. They were also the bailiwick of a more traditional internationalist wing of the Republican Party that had expanded VOA and created the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief—a flank that the Make America Great Again movement has aimed to vanquish. By the time that Trump’s billionaire former advisor, Elon Musk, came hunting for bureaucratic scalps, this hostility—coupled with the absence of a well-understood logic behind soft power—made these institutions easy prey.

While it arrived with an unwelcome jolt, the opportunity to reinvent U.S. soft power is timely. The United States does not just have limited will to reach into the workings of other societies—it also lacks credibility. In the 21st century, “nation-building” is a thing of the past, and any whiff of colonialism or political meddling has become taboo. Some leaders, including Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, have reacted to the cutoffs in U.S. assistance by saying, in essence, good riddance to programs that were shadowy, intrusive, and failed to yield self-reliance. Moreover, the United States’ liberal credentials have been sullied by rising populist authoritarianism at home.

And yet, hearts and minds still matter. Nye’s coinage of soft power resonated because it named an innate truth: Being liked and admired is important. Perceptions of strength, competence, technological prowess, economic clout, and general benevolence continue to shape geopolitics.

Beijing understands this well: As the United States has turned away from its traditional tools of reputation-building, China has waged an aggressive, expensive effort to style itself as a reliable global player, problem solver, and transactional partner. For any Trump successor, a soft power charm offensive will be essential to repair strained relationships and earn back seats at tables that Trump abandoned or overturned.

If U.S. soft power is to resurge, it will require grounding in a hardheaded logic that is responsive to the imperatives of today’s geopolitics. To reinvent soft power, Washington will need to articulate clear and compelling objectives; set out effective, resource-conscious, and measurable tactics for advancing those goals; and ensure that Congress—and to some extent, the general public—understand why it matters. Above all, future soft power investments will need to be tightly tied to U.S. national security and economic interests, such as the cultivation of specific allies, access to certain markets, or the promotion of U.S. technologies.

A reboot of U.S. development aid, in particular, must be more focused and strategic. This could be done on a leaner budget, especially if Washington pools aid with allies that share common aims. Of note, the European Union seems to be moving in a similar direction, proposing a budget that emphasizes private sector collaboration and eliminates binding development spending targets in favor of more flexible funding that can be used to advance varied interests. Cooperation with diaspora constituencies, corporations, philanthropic organizations, universities, and U.S. cities seeking new markets and investments could help stretch shrunken resources. By partnering with these institutions, Washington could co-create hubs for cultural and civic activities focused on U.S. values in addition to co-funding international exchanges. Such efforts would also help expose more Americans to the benefits of soft power diplomacy.

The future of development assistance could also build on one aspect of the development agenda that Biden accelerated and Trump seeks to turbocharge: the shift toward investment and finance as an alternative to aid. During his first term, Trump merged the Overseas Private Investment Corporation with USAID’s Development Credit Authority to create the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The Biden administration used the new agency to accelerate its climate agenda and help African countries leverage critical mineral resources.

The Trump administration is now proposing to vastly expand the agency and raise its financing capacity from $60 billion to $250 billion, motivated in large part by the drive to compete with China. While its approach is mercantilist rather than humanitarian, the agency can be a tool to deepen U.S. relationships globally and provide economic benefits to foreign populations by bringing in U.S. capital and expertise. A larger, more empowered DFC could even be a key building block for future soft power strategies.

In his 1961 inaugural address, then-President John F. Kennedy promoted development aid, proclaiming, “If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.” He spoke at a time of mostly robust economic growth at home, when income inequality was modest. Nearly 65 years later, Kennedy’s quote could be applied to the divides in the United States today. But as long as the United States remains a rich nation, there must be room for largesse and humanitarianism. Even the Trump administration has made exceptions to its slash-and-burn strategy, sustaining some funding for AIDS relief and emergency relief assistance.

It may be hard to get excited about a constrained, less aspirational future for U.S. engagement. But policymakers’ job is to craft approaches to advancing U.S. interests that match the moment and look to the future. Devotees of U.S. soft power know that helping others globally can stir the country’s better angels. For those who believe that Washington should stand for treasured values, and that the American people are compassionate at heart, the reset of soft power will offer an opportunity to rekindle those flames so that they may again gradually help to warm a cold world.

The post We’ve Forgotten What ‘Soft Power’ Is appeared first on Foreign Policy.