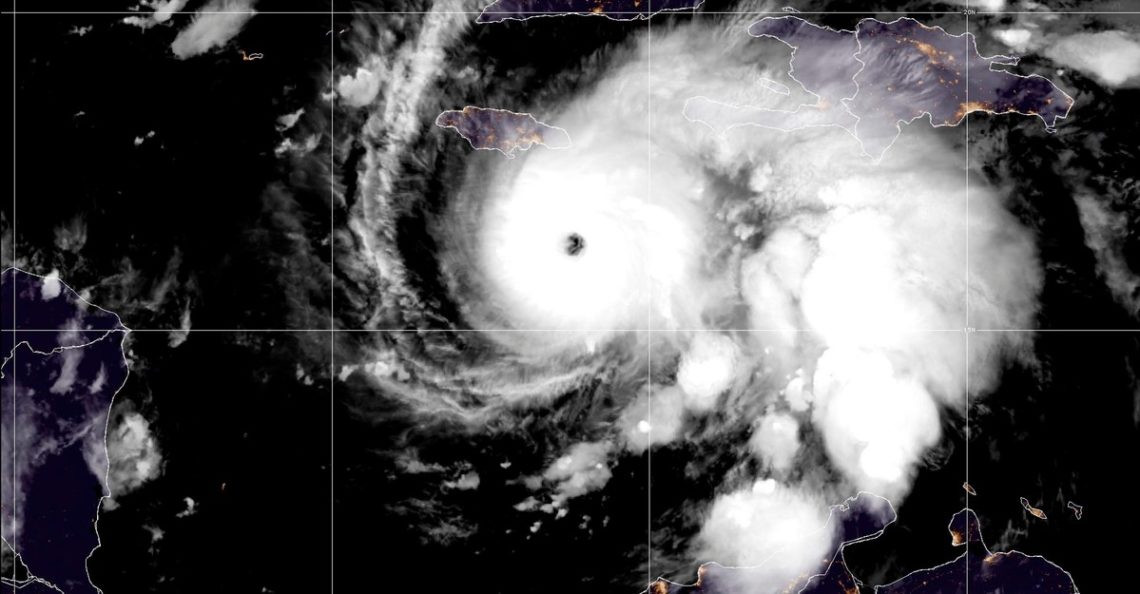

Hurricane Melissa is moving slowly. It reached the coast of Jamaica this afternoon after stalling out over the Caribbean Sea for the past two days. And yet, the winds that form Melissa are shockingly fast. At 10:00 this morning, the National Hurricane Center reported that maximum sustained winds had reached 185 miles an hour—surpassing those of any other storm this year, along with Hurricane Katrina.

That combination of high winds and creeping progress makes Melissa both unusual and unusually dangerous. Over the next day or so, the storm is on track to hammer Jamaica, eastern Cuba, and parts of the Bahamas with catastrophic flash flooding, destructive winds, and damaging waves. Jamaica’s prime minister has warned that the island’s infrastructure cannot withstand such a storm.

Like many other monster storms of the 21st century—and two others this season alone—Melissa intensified rapidly. From Saturday to Sunday, its winds doubled from 70 to 140 miles an hour. A second surge followed from Sunday to Monday, when winds climbed to 175 miles an hour, well above the threshold for a Category 5 storm. Andy Hazelton, a hurricane hunter and modeler at the University of Miami, told me he has been flying morning missions into Melissa’s eye since Saturday. (I am a journalist-in-residence at the University of Miami but have not previously collaborated with Hazelton or any of the other hurricane experts I contacted for this story.) Yesterday morning, turbulence was so intense that his flight had to turn back. “That’s happened in the past. It only happens in extreme hurricanes,” he said.

Melissa’s rapid intensification occurred even as it stalled near Jamaica, moving at about two miles an hour. “When a hurricane goes really slow like this, it usually churns up cold water that weakens it,” Hazelton said. But the waters of the Caribbean have been particularly warm this year. Sea-surface temperatures are about 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average, and deeper layers—the cold water that would normally sap energy from a slow-moving storm—have been lukewarm, even more than 100 meters deep. All of that heat is now being funneled from the ocean into the atmosphere. “I call it ‘higher-octane fuel,’” Lynn Shay, a professor of oceanography at the University of Miami, told me. He maps warm waters that could fuel hurricanes, in part by deploying sensors into hurricanes to study the air-sea interactions. He told me he has been unable to do so during Melissa because government-run flights have been short-staffed by the shutdown.

The previous major hurricane to hit Jamaica was Hurricane Gilbert, in 1988. But Gilbert moved much faster. Melissa, by contrast, is creeping forward “as fast as Miami traffic,” Shay said, which means that Jamaica has been battered by pounding waves since Saturday. The slow-moving storm is poised to drop up to 30 inches of rain on Jamaica, increasing the risk of life-threatening flooding, landslides, and long-duration power outages.

Michael Scott Fischer, an assistant professor at the University of Miami who studies rapid intensification, told me that evidence is emerging that rates of rapid intensification are becoming more extreme and that the phenomenon is occurring more frequently. He cautioned that the sample size is too small to directly attribute those trends to climate change; after all, only so many hurricanes occur in a season. “But it’s consistent with what we’d expect in a warmer world,” he said. Climate Central reported that the exceptionally warm waters that fueled Melissa’s rapid intensification were made up to 700 times more likely because of anthropogenic climate change. Some evidence suggests that the movement of hurricanes has also gradually slowed, which can lead to increases in rainfall totals. One such analysis published in Nature found that tropical cyclones slowed down by 10 percent from 1949 to 2016.

Hurricane forecasters predicted that this season would have 13 to 19 named storms, and so far, only 13 have materialized. But the storms that have formed have been exceptionally strong. Erin and Humberto also exploded into Category 5 hurricanes after rapidly intensifying earlier this year, marking the second season on record that three Category 5 storms have formed in the Atlantic. (The first time was in 2005, when four reached that strength: Emily, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, whose winds also topped out at 185 miles an hour.) “It’s like stacking the deck when you have these really warm sea-surface temperatures,” Fischer said. “It doesn’t guarantee you’ll draw an ace, but adding more aces to the deck increases the odds you will.” The Atlantic hurricane season doesn’t officially end until November 30, so “it’s too early to close the book on what this season has in store,” Fischer said. More aces may yet appear.

The post The Most Extreme Year for Atlantic Hurricanes in Two Decades appeared first on The Atlantic.