In March, James Proud, an unassuming British American without a college degree, sat in Vice President JD Vance’s office and explained how his Silicon Valley start-up, Substrate, had developed an alternative manufacturing process for semiconductors, one of the most fundamental and difficult challenges in tech.

For the past decade, semiconductors have been manufactured by a school-bus-size machine that uses light to etch patterns onto silicon wafers inside sterile, $25 billion factories. The machine, from the Dutch company ASML, is so critical to the chips in smartphones, A.I. systems and weaponry that Washington has effectively blocked sales of it to China.

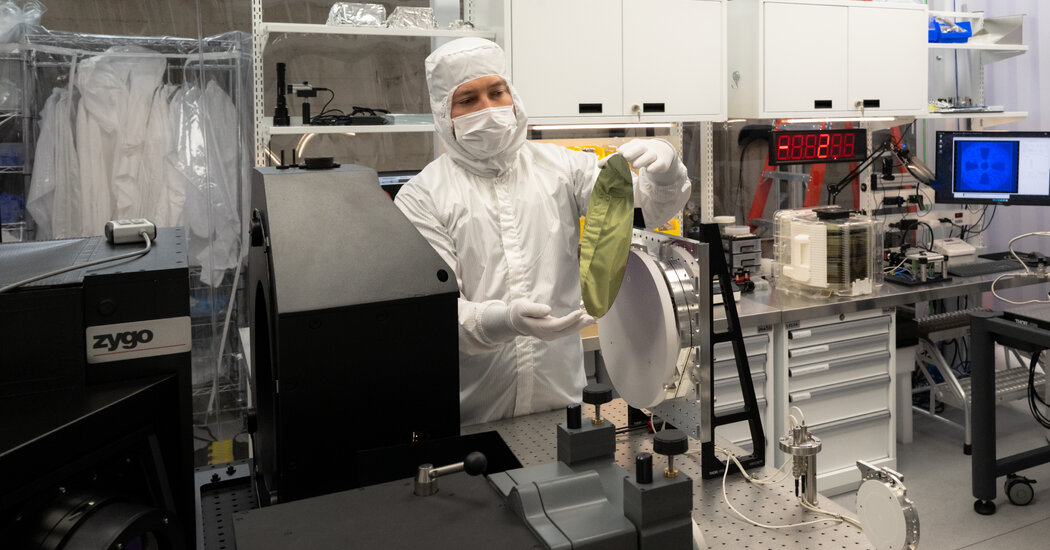

But Mr. Proud said his company, which has received more than $100 million from investors, had developed a solution that would cut the manufacturing cost in half by channeling light from a giant instrument known as a particle accelerator through a tool the size of a car. The technique had allowed Substrate to print a high-resolution microchip layer comparable to images produced by the world’s leading semiconductor plants.

“When did you do this?” Mr. Vance asked, according to Kyrsten Sinema, the former Arizona senator and the Substrate adviser who had arranged the meeting.

“Let’s just say I had a productive Covid, sir,” Mr. Proud said.

Substrate’s technical achievement, which has not been previously reported, builds on years of research into using particle accelerators to make semiconductors. For several decades, scientists have experimented with the machines, which speed up electrons so they hit a target at the speed of light. Some researchers have successfully printed images this way, but the process was never commercialized because of cost and reliability issues.

With construction of chip factories projected to double to $50 billion by the end of the decade, several start-ups have returned to the technology, believing it could help reduce soaring costs.

They are taking aim at one of the most difficult challenges in tech: changing how chips are made at the most fundamental level. It is a task so difficult that few have tried to do it in recent decades. And it explains why ASML has a 100 percent share of the market for these machines.

Mr. Proud, 34, is hoping to succeed where others have failed, by combining a proprietary particle accelerator with a custom lithography machine, which projects light through the blueprint of a chip design and onto a silicon wafer. He faces a long road between proving his process works and commercializing it. Success will hinge on his start-up’s clearing an array of business obstacles, including building a plant, finding customers and manufacturing at scale.

But as his March meeting with the vice president demonstrated, the United States is looking for every possible opening, however small or far-fetched, to reclaim leadership in semiconductor manufacturing and reduce the nation’s reliance on foreign producers.

To make his case, Mr. Proud has been sounding an alarm to officials in Washington. If his small company was able to make such a significant breakthrough, he said, then China, which has been building particle accelerators, may not be far behind.

The majority of today’s leading-edge semiconductors are made using ASML’s lithography machines at plants run by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Their dominance has created a supply chain risk, with TSMC making most of its chips in Taiwan, 100 miles from China.

“We’ve got a national-security supply-chain issue,” Ms. Sinema said in an interview with The New York Times. “Who wouldn’t want to partner with Substrate once that solution is commercially available?”

The vice president’s office declined to comment.

Substrate is the latest example of how semiconductors have gone from something Silicon Valley took for granted to one of its primary concerns. It is also a reminder of why the region, which has multiple particle accelerators, remains America’s start-up hub.

In addition to Substrate, xLight, which is in Palo Alto, Calif., wants to use particle accelerators to become the primary light source for future ASML tools. Japanese researchers are working with the technology as well.

Mr. Proud moved to San Francisco from London in 2011 as a member of the first Thiel Fellowship class, a college alternative for aspiring founders created by Peter Thiel, the venture capitalist. Mr. Proud sold his first company, a service that helped music fans find and buy concert tickets, but his second start-up, Hello, which made a sleep-tracking device, folded after selling some of its technology to Fitbit.

In 2019, Mr. Proud was beginning to work on another start-up to support device makers when he started to study the semiconductor supply chain. His research coincided with China’s starting to crack down on democracy and seize power in Hong Kong. He was concerned the country could do the same in Taiwan, an island China wanted to reclaim.

Mr. Proud, who became a U.S. citizen in 2019, put together a policy paper for the first Trump administration, calling for a Manhattan Project for U.S. chipmaking. “This is going to be a problem, and it’s going to get worse,” Mr. Proud said he had told administration officials.

After the Trump administration persuaded TSMC to build a plant in Arizona, Mr. Proud decided to build his own company. He and his brother Oliver, 25, started reading books and academic papers on semiconductor lithography. They questioned why the process had become so complex and expensive.

One of the major costs in modern lithography machines, which have more than 100,000 parts, is how they use high-powered lasers to turn droplets of molten tin into a burst of extreme ultraviolet light. The machines use the light to etch a wafer of silicon in a process known as EUV lithography.

Another process that had never been commercialized involved particle accelerators. The machines, which are used largely by researchers, could act as a light source to pattern designs on wafers in a process called X-ray lithography. ASML had tested but abandoned the technology.

The Proud brothers thought it could be commercialized with a custom particle accelerator and lithography tool. In January 2022, they co-founded Substrate in San Francisco.

Mr. Proud, who had no experience with particle accelerators, hired a particle physicist and an optics expert experienced with using particle accelerators at U.S. national laboratories. The team would expand to 50 people, including some engineers from TSMC, IBM and Google.

Substrate operates out of an industrial warehouse near San Francisco’s Design District. The space is divided in half by a 12-foot-tall American flag, and the visitors’ waiting area features books like “The Next Major War: Can the U.S. and Its Allies Win Against China?”

The team spent much of 2023 building a custom lithography tool. It featured thousands of parts and was small enough to fit in the back of a U-Haul. They tested it in computer simulations.

In early 2024, Substrate reserved a Bay Area particle accelerator for a make-or-break test. The company ran into problems when vibrations near the particle accelerator caused the tool to gyrate and blur the image, Mr. Proud said.

A frantic, daylong search found that the air-conditioning system was causing the vibration. Substrate adjusted the fan speed until the process printed “very beautiful and tiny things repeatedly” on a silicon wafer, Mr. Proud said.

The team has since built larger and more complex tools and printed images that match the resolution of the latest, cutting-edge process for making chips.

Mr. Proud can be secretive about Substrate’s process. He declined to provide information about which particle accelerator the company had used in its test or about some of its custom components. He said Substrate was following the example of some artificial intelligence companies, which don’t openly share their work.

John E. Kelly, who helped pioneer semiconductor manufacturing techniques at IBM and reviewed the images at Mr. Proud’s request, said they “are extremely good, extremely clear,” and showed that a very complex technical process worked.

But Mr. Kelly said Substrate needed to take considerably harder steps, including building a multibillion-dollar factory, finding customers and licensing some technology from established companies.

“He’s at the first base camp,” Mr. Kelly said of Mr. Proud. “He’s still got a long way to go to reach the top of Everest.”

Another challenge Substrate could face comes from its plan to use a particle accelerator to provide a single-light source that feeds several of its tools simultaneously, semiconductor engineers said. That can reduce cost, but a malfunction could idle a plant using it.

Such concerns led the Biden administration to resist Mr. Proud’s initial requests for more than $1 billion in funding from the CHIPS Act, a bipartisan bill to subsidize U.S. chipmaking, said two people familiar with the confidential deliberations.

Mr. Proud said that the Commerce Department had never formally rejected Substrate’s request. He also said the company’s manufacturing process was designed to avoid downtime.

Substrate is valued at more than $1 billion with funding from several investors, including Founders Fund, General Catalyst, Valor Equity Partners and Allen & Company. But Mr. Proud will have to raise much more.

Last year, the company started searching for a site for its first factory. It has held discussions with Texas A&M University about building a particle accelerator and plant on its campus for about $10 billion.

Mr. Proud said he had also held preliminary discussions with Intel, the veteran Silicon Valley chipmaker, about its technology.

Intel declined to comment.

When asked about the challenges ahead, Mr. Proud bristled. During a recent interview, he recalled that people had said an alternative lithography process couldn’t be done, but he pushed ahead because “the downside, if we don’t do this, is a complete catastrophe.”

“If you have only two bad options,” he said, “you need to go and invent a third, better option.”

Adam Satariano contributed reporting from London, and John Markoff from San Francisco.

Tripp Mickle reports on some of the world’s biggest tech companies, including Nvidia, Google and Apple. He also writes about trends across the tech industry like layoffs and artificial intelligence.

The post Can a Start-Up Make Computer Chips Cheaper Than the Industry’s Giants? appeared first on New York Times.