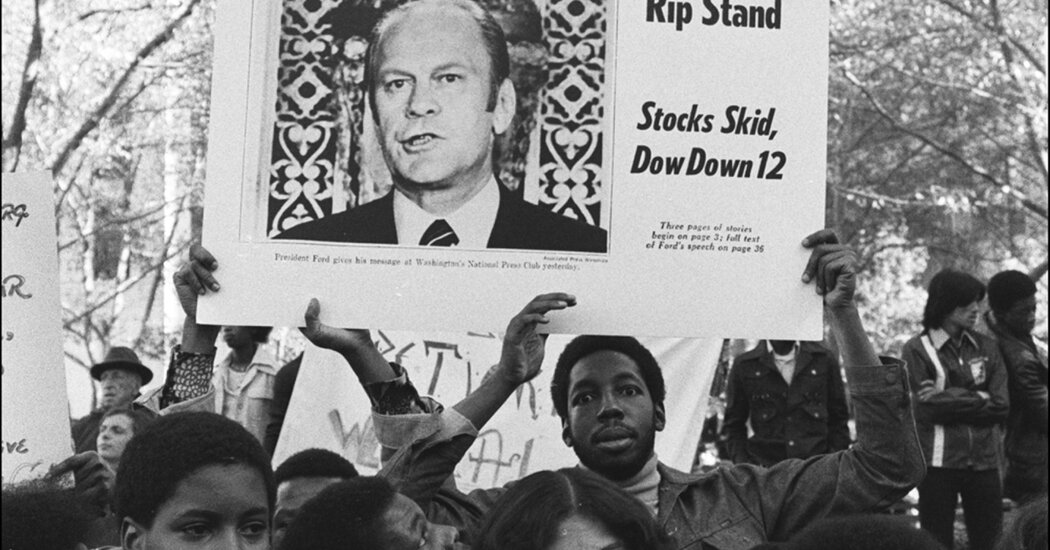

Fifty years ago this week, The Daily News published a headline that, in five words, helped turn the tide on a financial crisis that had held New York City in its grip for months. Landing with a thud on newsstands, it was an instant classic and remains one of the most famous headlines in history: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

On that Thursday morning, Oct. 30, 1975, millions of New Yorkers got the message — federal assistance to the city, which only weeks earlier had come within minutes of bankruptcy, would not be forthcoming. In a speech the previous day, President Gerald Ford had made clear that he wasn’t going to let Northeastern liberals off the hook for their profligate social spending. But he never actually said “drop dead,” choosing a metaphor instead: “Responsibility for New York City’s financial problems is being left on the front doorstep of the federal government — unwanted and abandoned by its real parents.”

Ford’s response was punitive and ideological, and the headline distilled the polarization of the moment. His message was aimed at voters hundreds and thousands of miles away in flyover states, where the battle for the Republican Party was unfolding. The demonizing of cities for the benefit of a rural audience had been a winning strategy in the past, and in 1975 two advisers to the president were convinced that the city’s travails provided another perfect political opportunity.

Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney were young conservatives who, in 1975, had found solid footing at the pinnacle of American political power — Mr. Rumsfeld as Ford’s chief of staff and Mr. Cheney as his deputy chief. Both seemed to detest New York’s liberal brand and saw in the city’s demise a chance for Ford to claim an anti-urban platform. It was also an opportunity to counter a surging rightward threat from Ronald Reagan, who was on a path to challenge Ford for the nomination to the Republican ticket in 1976.

In an interview for a documentary we made about the 1975 fiscal crisis, David Gergen, one of Ford’s advisers, told us that Mr. Cheney had asked him to write a tough speech for the president that would castigate the city for its fiscal irresponsibility. Mr. Gergen assumed the speech would be watered down. It wasn’t. (For the managing editor of The Daily News, William Brink, who wrote the headline and made sure it would fill the page for maximum impact, Ford’s opportunity presented an opportunity of its own — expressing the outrage of millions of New Yorkers.)

Today, much is the same: a White House that demonizes cities, and a pointed, almost personal rebuke from the president toward entire cosmopolitan populations. But where Ford’s posture of chiding disdain was shaped by his Midwestern reserve — he said what he wouldn’t do and left it at that — President Trump is all violence and action, even suggesting that cities might serve as “training grounds” for the military.

Today, as in 1975, a vast majority of America’s largest cities have Democratic mayors, and in little over a week New York City may elect its most progressive mayor since John Lindsay. Cities embody everything that politicians like Mr. Cheney, Mr. Rumsfeld and Ford seemed to dislike and that MAGA claims to despise. They’re messy, complex mosaics of sexual, ethnic and cultural difference. While Mr. Trump promises to “Make America Great Again” and return to a nostalgic version of a “true” America, cities represent places where immigrants (some of them poor, nonwhite and uneducated) crowd together to forge themselves, and the country, into something new.

Hard things are hard, and in the 1970s, as today, numerous governmental failures and inefficiencies provided the anti-big government right with obvious targets. There was much to critique in this era: rising crime that, along with crumbling infrastructure, helped spur white flight, which in turn pushed down tax revenues.

Coupled with a perfect storm of a national recession and years of horrific mismanagement by elected officials, including the mayor, Abraham Beame (who had run on the slogan “He Knows the Buck” to highlight his experience as the city’s comptroller), New York spent and spiraled its way into insolvency. It became the poster child for dysfunction, and Ford leaped to make an example of it.

Mr. Trump is trying to score political points by citing supposedly crime-ridden cities as proof of the failure of the liberal ideal. But unlike Ford, he’s conjuring a specter of New York with little basis in reality. While the city does have serious problems — most obviously an acute housing shortage and a general crisis of affordability — the dismal metropolis that Mr. Trump invokes doesn’t exist.

Even so, he threatens to send federal troops to restore order to the city, which in the first five months of the year experienced its lowest number of shootings and murders in recorded history. (It’s worth noting that this summer, before Mr. Trump said he would send the National Guard to Chicago, that city counted its lowest number of homicides since the 1960s. Crime is also down in other Trump targets, including Los Angeles, Washington and Portland, Ore.)

But when it comes to attacking cities, the 1970s holds some surprising lessons — and perhaps some hope.

Ford’s message to New Yorkers gave them a sense that they were all in the same boat and inspired the realization that it was up to them to find a way to resolve the fiscal crisis. Despite the Ford administration’s antipathy for East Coast liberalism, punishing terms from Wall Street and the city’s history of chronic economic and social disputation, New York City rose to the challenge. Its rescue forced unions, banks, politicians and state and local institutions to work together to carve out a fiscal framework that enabled the city to balance its budget. This unlikely alliance was as remarkable as the disaster itself.

Ultimately, it’s notable that Ford’s cynical political calculus backfired. The day the “Drop Dead” headline ran was, in many ways, the day he began to lose the White House. In the 1976 presidential election, Ford earned only 48 percent of the New York state vote; four years earlier, his predecessor, Richard Nixon, won the state in a landslide.

Ford’s loss of New York’s 41 electoral votes helped put Jimmy Carter in the White House. Ford later pointed to the headline as a decisive factor in his defeat.

It remains to be seen whether Mr. Trump, who doesn’t face another election, will learn a similar lesson. But his MAGA supporters, with more to lose, would do well to remember: Mess with cities like New York at your own peril.

Michael Rohatyn is a filmmaker and musician whose father, Felix Rohatyn, was a key architect of New York City’s 1975 fiscal rescue plan. Peter Yost is the founder of Pangloss Films.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Trump to Cities: Drop Dead appeared first on New York Times.