U.S. President Donald Trump has angered many Americans who have watched videos of the demolition of the East Wing of the White House. The stunning visual of the torn-down building symbolizes to many how Trump views the presidency. This highest honor has become, in his hands, a tool for pursuing his own goals without concern for tradition, precedent, and history. Despite all the memories of receptions and meetings that filled the air of those hallowed halls, Trump has torn the wing down to the bones so that he can build a ballroom for high rollers and opulent functions.

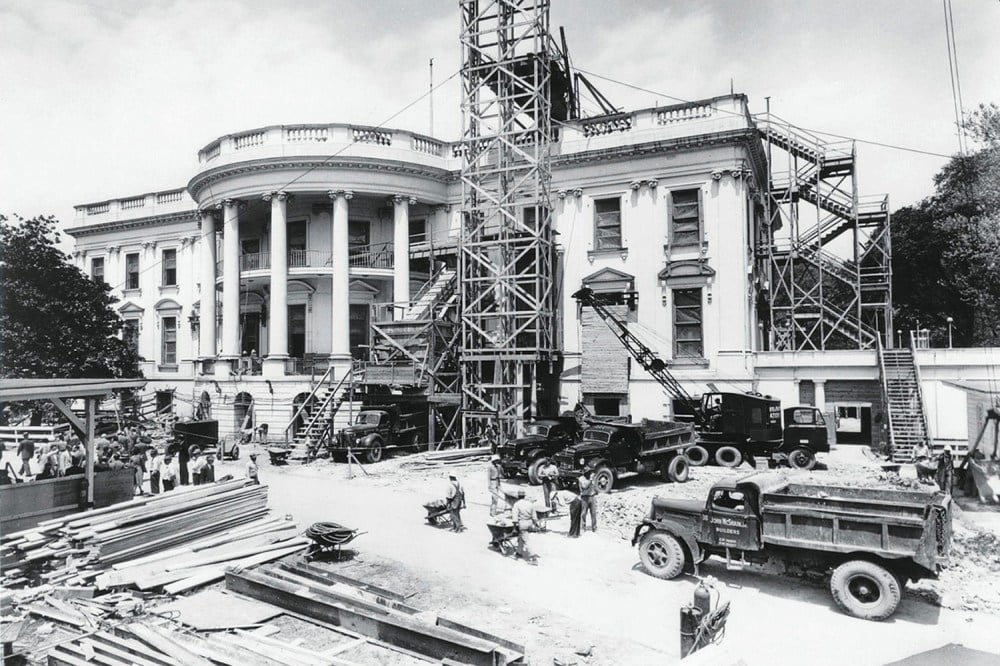

As the criticism mounted quickly, Trump pushed back, reminding the press that he is simply part of the “proud presidential legacy” of renovating this important place of work and residence. And it is true that this is not the first time that the White House has undergone renovations. The most interesting contrast is with President Harry Truman’s renovation. While Truman’s remodeling also received a lot of criticism and partisan attacks—as with Trump’s—the process was much different. Examining that case reveals the significance, and danger, of what is happening today.

-

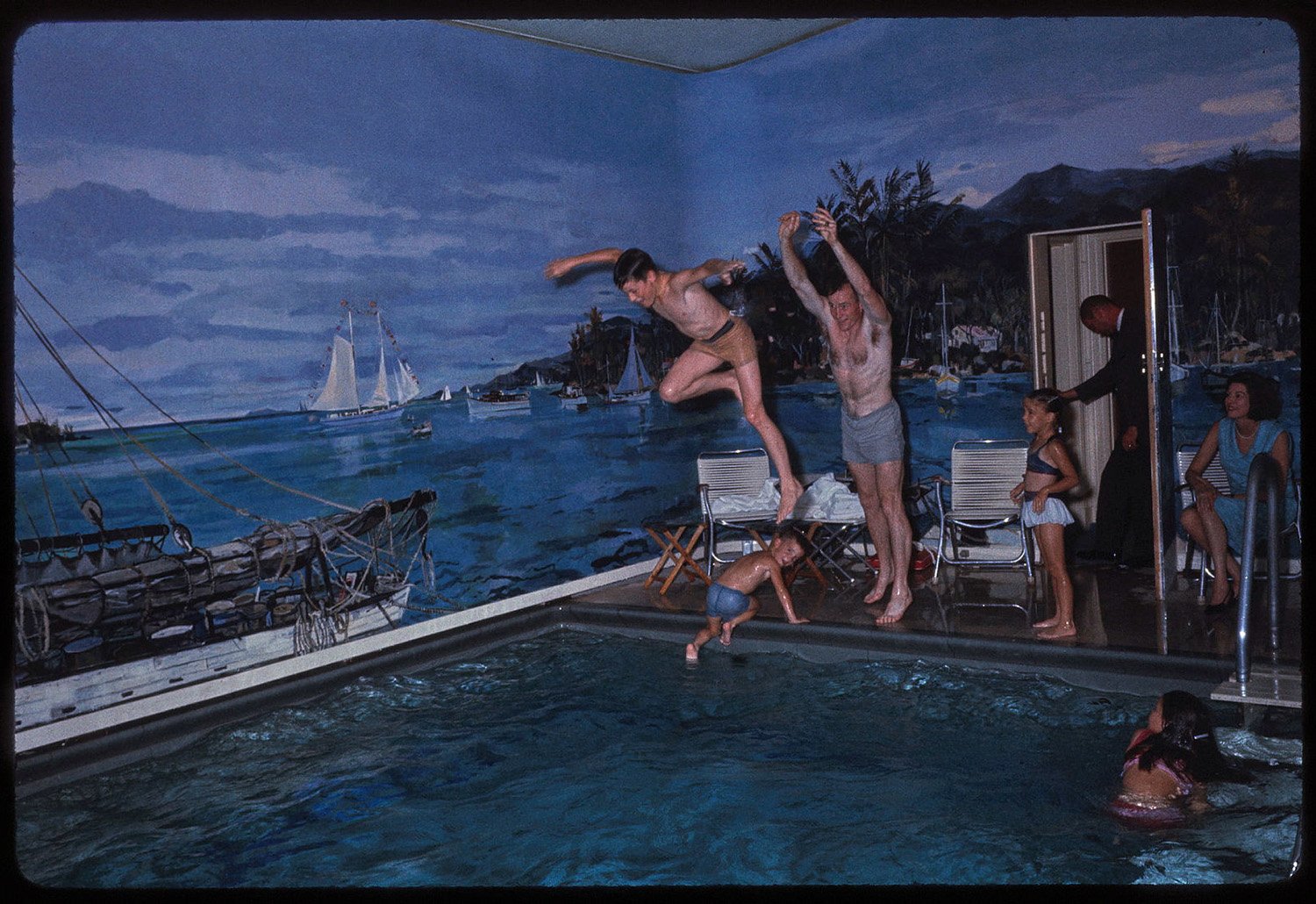

A shirtless man and boy jump into a pool. Children swim or stand on the deck nearby, with a woman in a blue dress seated behind them and a man in a suit standing in a doorway. The walls of the pool area are painted with a nautical scene.

-

Nine children are seated in the front two rows of a curtain-draped movie room with multiple rows of plush chairs. The children are dressed in suits and dresses with their feet resting up on stools.

White House renovations have taken place for centuries. After the British burned down the original White House during the War of 1812, a new building had to be almost entirely reconstructed from the bottom up, completed in 1817. In 1881, President Chester Arthur added Tiffany windows for a dash of decorative flair to his surroundings, while in 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt authorized an expansion, including the creation of the West Wing. The Roosevelts also undertook substantial refurbishing on the inside to bring the White House into the modern stylistic era.

The now-former East Wing was erected in 1942, when Franklin Roosevelt was president. The main goal of the addition was to conceal an underground bunker that would be used to protect the president and his family in times of emergency, though the space soon became an area that was used by the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and visitors for entertaining. Roosevelt also installed an indoor swimming pool as part of his therapy for polio.

First lady Jacqueline Kennedy dramatically changed the White House’s interior décor, adding classic museum pieces to showcase U.S. history while introducing a touch of Kennedyesque glamor. To save energy, President Jimmy Carter installed water-heated solar panels, while President Barack Obama updated the Oval Office furniture and added a basketball court.

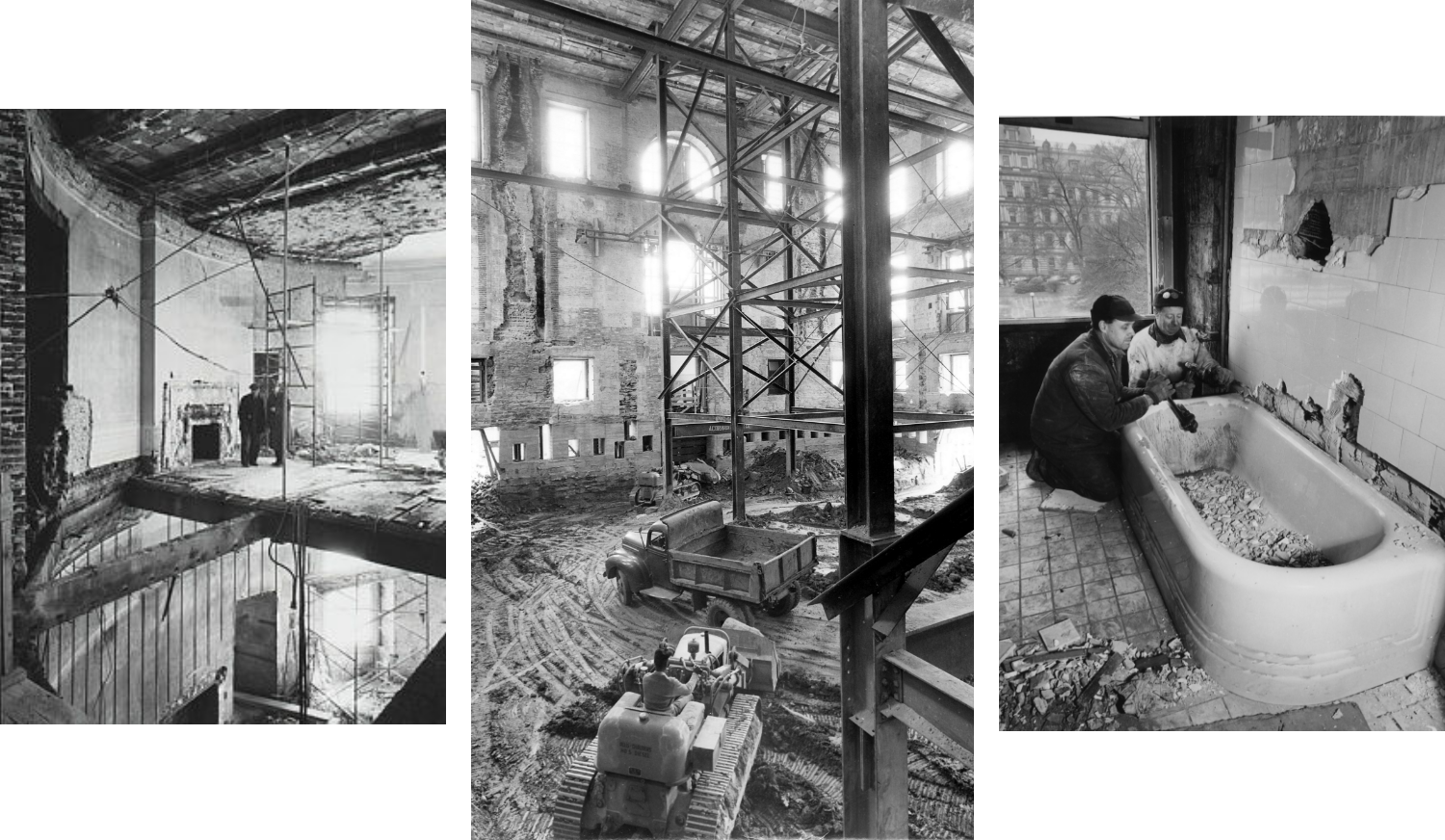

The most dramatic renovations since 1817 took place between 1948 and 1952, when Truman was president. The entire interior of the White House was gutted and rebuilt. President Truman and his family lived in Blair House throughout this period. What is most striking is how different the rationale, the construction process, and Truman’s attitude were from Trump’s.

Truman wanted to move forward with the project because the White House was in dangerously poor condition. When he moved into the building in 1945, after Franklin Roosevelt died, he immediately noticed large patches of cracked plaster. The architect Lorenzo Winslow found troubling signs that the building might literally be on the verge of collapsing as he was working on a balcony on the South Portico in 1948.

Conditions became even more dramatically clear when the leg of a piano owned by the president’s daughter, Margaret, broke through the floor in the sitting room. The president’s bathtub was also falling through the floor and could be seen from the dining room underneath.

According to columnist Doris Fleeson writing at the time, “There were practically no closets beyond a few installed by Mrs. Roosevelt, bathrooms were a blush-evoking problem, stairs were a hazard and real privacy a scarce luxury.” Just as important, the massive expansion of the executive branch in the 1930s and 1940s required more staff space.

As experts surveyed conditions, there wasn’t much disagreement on the need for serious repair. In 1949, Congress and the president created a bipartisan Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion to handle the project in a judicious manner. The commission included one of the nation’s most distinguished architects, Douglas Orr, who was also the president of the American Institute of Architects, as well as the president of the American Society of Civil Engineers, Richard E. Dougherty. They were joined by several senators and representatives.

The commission conducted a thorough survey of the building, and it proposed several plans for moving forward. Truman persuaded the commission to abandon the idea of tearing down the entire building, as he sought to preserve the historic walls. “It will be no small task to renovate and modernize the structure,” Truman, a voracious reader of history, said. “It perhaps would be more economical from a purely financial standpoint to raze the building and to rebuild completely. In doing so, however, there would be destroyed a building of tremendous historical significance in the growth of the nation. I am in favor of preserving our outstanding historical structures.”

In October 1949, Congress approved the plan and allocated about $5.4 million. Once all of the contracts were in place, the work began in December 1949.

The scale and scope of the project was immense. While living in Blair House starting in November 1948 and dealing with the expansion of the Cold War and an ambitious domestic agenda, Truman remained very involved in the project. Though respectful of the experts handling the job, the frugal president wanted to make sure that costs were as contained as possible and that the workers did whatever they could to preserve the historical integrity of the building.

-

Workers kneel as they lay flooring tiles in a disheveled hallway in the White House with high ceilings and tall arched doorways. A bare lightbulb hangs from an exposed wiring system overhead.

-

An above view shows a dismantled stairwell with exposed damaged walls and workers at the bottom, wearing gloves as they lift stones.

At his suggestion, materials from the old building were repurposed for the new interior. The famous chandeliers from the Blue Room and East Room were put back on the new ceilings. Fireplace mantels from the 1800s were brought back. One of the biggest additions, which came from the president’s recommendation, was the Truman Balcony on the second floor of the South Portico, which he funded himself.

It is true that criticism has often followed renovation projects, and Truman was no exception. As the work unfolded, dissenting voices emerged from the press and Capitol Hill. As jarring photographs of a torn-down White House generated shock among the public, some journalists started to raise questions about the high cost of the renovation at a time when many Americans were still in recovering from the impact of World War II and embroiled in the Korean War. There were also concerns about whether the designers had done enough to preserve the historical elements of the White House.

Some of Truman’s opponents didn’t waste the opportunity to use the construction as a reason to go after Truman about public spending and the contractors who were connected to him. The project had gone on longer than expected and cost more.

After Congress had passed a supplemental budget in 1951 to pay for some additional work, the Truman family moved back in on March 27, 1952. Truman had arrived from a three-week stay at his “Little White House” in Key West, Florida, tan and rested.

“I am very glad to move back into the President’s house,” he told the press. The renovation commission published a final report at the end of the year, and the $5.7 million project (more than $60 million in today’s dollars) came to an end.

Regardless of the controversies that surrounded the Truman White House project, the people’s building needed the work, and Truman relied on clear, bipartisan processes through Congress that made sure that the history of the institution would be honored and that there were clear rationales for each piece of the project. Notwithstanding partisan debates about the costs and contractors, there was little doubt that the new White House would be a monument to U.S. democracy—not to Truman.

What the nation has seen in recent days is fundamentally different than what happened with Truman. At this point, there little understanding or agreement that this project was necessary. The president said in July that he would not tear down the East Wing. Now he has. As opposed to creating a space that would be physically safe or enhancing the existing environment in careful, judicious fashion, this vanity project—especially tearing down the East Wing—has no immediate justification.

Nor is it apparent that there have been clear processes in place to think through and guide the work with respect for the past. The National Capital Planning Commission does not appear to have been consulted, nor was the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Furthermore, and perhaps unsurprisingly from an administration that has repeatedly shown its willingness to test the boundaries of ethics, the project is being paid for by major private donors that have a vested interest in government policy.

Finally, there is little confidence among much of the public that Trump is undertaking this with an eye on the nation’s best interest as opposed to his own.

Ironically, Trump has issued an executive order to call for the restoration of Confederate monuments, most of which were put into place as symbols of opposition to Reconstruction and civil rights. Yet when it comes to the White House—in which Democratic and Republican presidents alike have made pivotal decisions that changed the course of history—he seems eager to tear everything down.

The post How Trump’s White House Renovation Differs from Truman’s appeared first on Foreign Policy.