Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

Alice Callahan, a reporter for the Well desk at The New York Times, knows most ultraprocessed foods aren’t good for her.

But as a working mother who juggles reporting with school pickups and sports practices, she acknowledged that convenience often wins.

“My kids do eat flavored yogurt that’s ultraprocessed,” said Ms. Callahan, who has a 14-year-old daughter and a 10-year-old son.

The allure of an easy quick meal or a tasty snack that you can grab and go is real. In fact, more than half of the calories Americans consume each day come from ultraprocessed foods. But research suggests that consuming too many of these foods can raise risks of obesity, Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other health conditions.

So Ms. Callahan, who covers nutrition and health for The Times, wanted to know: How did ultraprocessed foods, or foods you couldn’t typically make in your own kitchen, become so dominant in the United States?

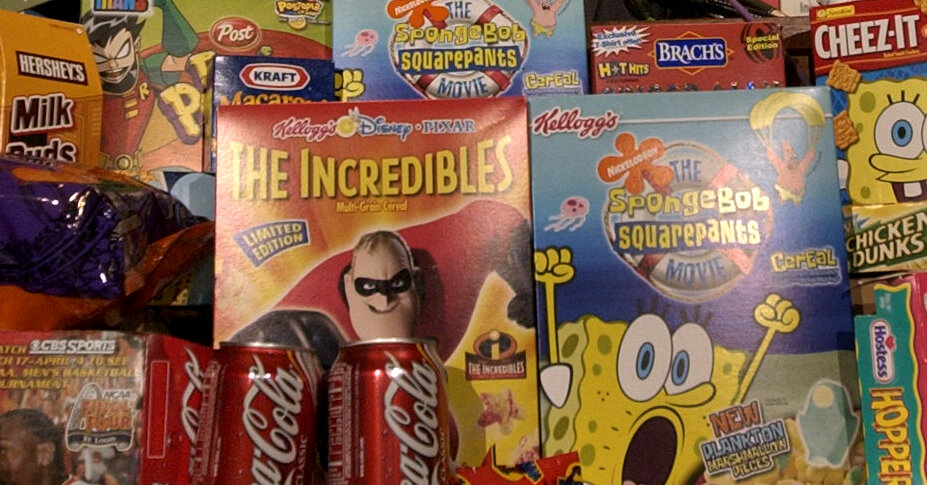

Her resulting article, four months in the making, dived into that question. It explored how ultraprocessed foods like Wonder Bread and certain frozen meals, which initially promised convenience and cheap nutrition, became a health threat.

In an interview, Ms. Callahan shared the surprising sources she turned to in her reporting, and how what she learned would — and would not — change the way she grocery shops. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

How did you get the idea for this article?

In the last few years, we’ve been hearing more from scientists, influencers, even from politicians and federal officials, about the risks of ultraprocessed foods. People in the United States consume more ultraprocessed foods than those in just about any other country in the world. So the discussion is now turning to: What are we going to do about it? How can we decrease our reliance on these foods? It felt important to understand how we got here if we were going to be able to do anything to change it.

Why is the problem so bad in the United States?

One thing that sets us apart is that we have often been on the leading edge of technological advances. For example, television became ubiquitous in homes in the United States earlier than it did in much of the rest of the world. That created this new avenue for food marketing, which was used heavily to sell moms and children on these new foods, going back to the 1950s.

As time went on, the foods were formulated to be more and more irresistible, making us want to come back for more, which is great for sales, but not so good for health.

What was one thing you learned while reporting that might surprise to readers?

The recognition and scientific study of ultraprocessed foods actually started outside the United States, when scientists in Brazil became alarmed at the rising rates of obesity they saw after the foods were introduced there.

The story of ultraprocessed foods in the United States is a coalescence of economic, cultural, scientific, technological and political forces. Were there any unexpected sources you consulted?

Usually, I talk to scientists and food policy experts for most of my reporting. But this piece also took me deep into history books, and I interviewed several culinary historians. It took me into food science; I needed to understand how we got from corn to corn syrup and modified cornstarch, and how each of those ingredients affects our bodies differently, even though they come from the same crop. I also talked to former company executives to better understand the food industry and the development and marketing of food products.

Some of the most interesting sources were food company documents. I was sifting through annual reports from PepsiCo, for example, which owned Frito-Lay, as well as documents from Kraft and General Foods, which were owned by tobacco companies. Those documents tell interesting stories, especially when you look at the 1980s, when companies were introducing a lot of new snack foods. It wasn’t just plain potato chips; it was multiple flavors of potato chips. They were learning that the more flavors and varieties they introduced, the more they would sell. Research now shows that the more varieties of foods we have available, the more we tend to eat.

I also love digging through old Times articles from each of these eras, seeing how reporters decades ago were covering trends in food.

Do you eat ultraprocessed foods?

I do, though I try to minimize them. As much as possible, I cook with whole foods, or with foods that may be considered ultraprocessed, but that offer some health benefits. I’ll make sandwiches with whole wheat bread, for instance, which is technically ultraprocessed, but is also a good source of fiber. It’s really hard to avoid ultraprocessed foods entirely, especially if you have kids.

How did reporting this story change the way you approach grocery shopping?

It made me think about the power of marketing, because that has been a theme in the history of ultraprocessed foods going back to the late 1800s, when Coca-Cola and Jell-O were introduced. We’re bombarded with a lot of different messages about nutrition, and it can be hard to separate out what is science-based.

What questions do you still have?

I’m really interested in studies that are trying to tease out why we so easily overconsume ultraprocessed foods. If we can understand why that is, is it possible for food companies to make healthier foods that are still convenient, shelf-stable and easy for a busy parent like me to serve to my kids?

Sarah Bahr writes about culture and style for The Times.

The post Going Down the Junk Food Rabbit Hole appeared first on New York Times.