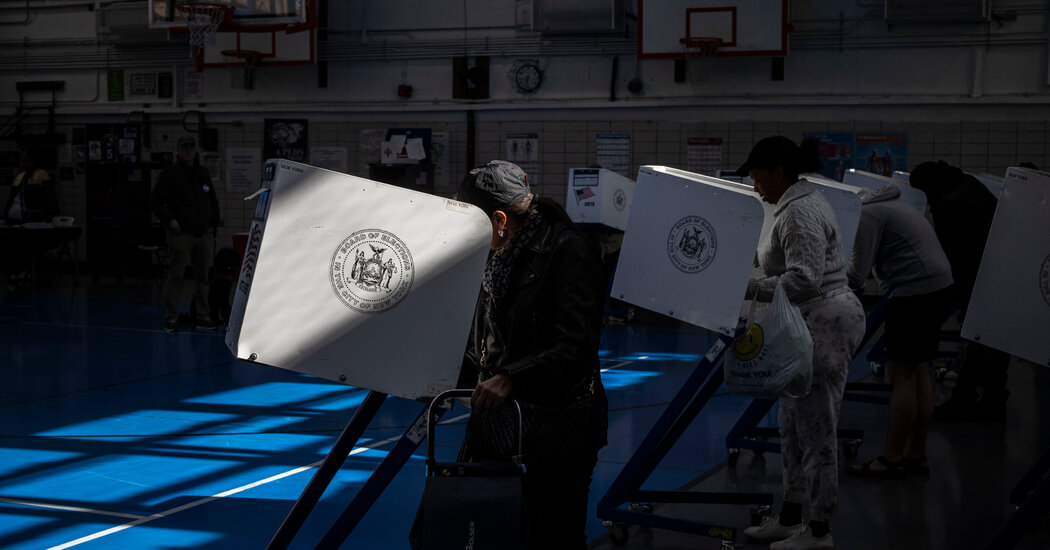

More than 160,000 New Yorkers flocked to the polls this weekend to give an energetic kickoff to the start of early voting in the bitterly contested election for mayor, with the candidates’ attack lines hovering over an unusual three-way race.

The pace of early voting so far suggested high turnout for an off-year election, reflecting heightened interest in the contest. Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic nominee, has been the steady front-runner in polls; former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo, who is running as an independent, has been running second; Curtis Sliwa, the Republican nominee and Guardian Angels founder, trails in third.

Mr. Mamdani defeated a field of better-known rivals, including Mr. Cuomo, in the Democratic primary, attracting a diverse coalition of supporters through his messaging on affordability and his ability to spread that message to millions through social media. He also built a formidable base of small-money donors and a grass-roots ground game that swamped his rivals.

That canvassing advantage was on display this weekend, even as workers backing Mr. Cuomo and Mr. Sliwa hunted for votes too.

On Saturday, about 2,200 volunteers for Mr. Mamdani canvassed citywide while another roughly 800 made calls. Many were voters like Mike Woodsworth, a public-school teacher, who said he was worried about Mr. Cuomo’s efforts to try to push Mr. Sliwa out of the race. Not wanting to sit on the sidelines during this perilous moment nationally, he decided to not just vote for Mr. Mamdani but canvass for him for the first time as well.

Mr. Wordsworth set off to canvass from a park in central Brooklyn, where later in the day roughly 40 volunteers gathered. A choir had just serenaded many of them with songs said to be inspired by Mr. Mamdani’s policies and initiatives. Some had come out for the first time; others traveled from out of state. Some had voted in dozens of mayoral elections; others had not voted or were ineligible.

But they were all excited by Mr. Mamdani’s polling lead and the prospect of electing a mayor on Nov. 4 with a different vision for the city.

“To have the chance to be part of a moment that is so transformative and based on such a positive vision for the city,” said Zack Littlejohn, 23. “It’s intoxicating.”

About 90,000 people have volunteered for Mr. Mamdani since the campaign launched last year, with about 40,000 volunteers joining up after the primary, the campaign said. Volunteers supporting Mr. Mamdani have knocked on 158,000 doors since last Monday, according to the campaign.

At one home in the Kensington section of Brooklyn, Mr. Woodsworth met Gaitry Singh, 78, a Guyanese immigrant who was about to leave for one of her two jobs teaching children with special needs. At first, Ms. Singh was reluctant to engage.

Mr. Woodsworth quickly framed his pitch around their shared teaching backgrounds and the federal cuts to educational programs. As she headed to her son’s car, she said she would give Mr. Mamdani a close look and most likely would support him.

Her son, idling in his car nearby, said he had already decided to back Mr. Mamdani because, he said, the city needed fresh blood.

Hoping he had locked in Ms. Singh’s support, Mr. Woodsworth high-fived Taylor Ramsey, a fellow volunteer. They both said Mr. Mamdani provided a dose of much-needed optimism: Ms. Ramsey found work at a city agency after losing her job with USAID earlier this year when the agency closed during President Trump’s waves of cuts across the federal government.

“This has been a campaign of joy,” Ms. Ramsey said. “It’s been so wonderful to be part of it.”

Filling a void in the field

After his double-digit primary loss, Mr. Cuomo was criticized for relying too heavily on paid advertising and failing to build a grass-roots operation. In recent weeks, he has tried to consolidate support among more moderate Democratic voters while also appealing to Republicans. This week he picked up endorsements from The Staten Island Advance and The Daily News.

His bid has also been supported by a patchwork of super PACs trying to drum up support — particularly in working-class neighborhoods outside Manhattan.

One such super PAC, Fix The City, sent workers across all five boroughs over the weekend to knock doors and generate enthusiasm for the former governor’s campaign. By Election Day, the group plans to knock 350,000 doors and will have spent about $4 million on its field operation, according to a representative for the group — an unusually large sum, as PACs tend to focus largely on advertising over grass-roots efforts.

“I see this as yet another shot of adrenaline in the arms of people to just move,” said Jessica Haller, who leads the group’s direct outreach campaign. “It’s just continuous energy. I think the next 10 days is just going to be energy, energy, energy.”

With the help of about 650 volunteers, the group, which spent close to $25 million supporting Mr. Cuomo during the primary, has so far knocked on about 126,000 doors and made about 125,000 calls to voters since the primary. Their teams could be spotted at polling sites across the city on Saturday handing out literature and gear in a variety of languages.

In Brighton Beach, a conservative Brooklyn neighborhood filled with Russian-language speakers, Cuomo supporters navigated broken elevators and distrustful residents in hopes of persuading voters to abandon Mr. Sliwa and vote for the former governor, who continues to angle for Republican votes. The canvassers included Ilya Rubinstein, a Sheepshead Bay resident who opposes Mr. Mamdani partially because of his views on Israel.

Mr. Rubinstein, originally from Belarus, knocked on doors to try to convey what he views as the former governor’s seriousness and managerial chops to residents like Larisa Feldman, who was deciding between backing Mr. Sliwa or Mr. Cuomo. Mr. Mamdani’s support of democratic socialism was disqualifying, she said.

“Money doesn’t fall out of the sky,” Ms. Feldman said in Russian.

The effort in Brighton Beach was being funded by another super PAC, New Yorkers for a Better Future, one of the other outside groups opposing Mr. Mamdani that has raised about $1.5 million for this work.

About 60 canvassers were focused that day on Russian speakers in Sheepshead Bay and Brighton Beach.

The group has also deployed micro-targeted messaging to Chinese voters about Mr. Mamdani’s positions on gifted and talented programs and his past position on the test to enter specialized high schools. He was long skeptical of the test’s fairness, but now says he would keep it.

“They are doing digital advertising and mailers, but one thing that seems to be lacking is field work,” Jeff Leb, a political operative leading the super PAC, said about the Cuomo campaign. “The outside groups are trying to fill the gap and make up for what we feel is missing.”

A spokesman for Mr. Cuomo did not respond to several inquires about the campaign’s efforts to turn out voters.

‘The last people voters will see’

Mr. Cuomo may have labeled Mr. Sliwa an unserious candidate, but the Republican’s campaign suggests otherwise. Phyllis Inserillo, its director of get-out-the-vote operations, said the campaign had opened 10 field offices across the city and pulled in thousands of volunteers.

Between door knocking, dialing voters and distributing campaign literature, Ms. Inserillo estimated there were about 1,000 volunteers out on Saturday supporting Mr. Sliwa.

“These canvassers are the last people voters will see before they go in to vote,” Ms. Inserillo said.

As with the Mamdani campaign, the start of early voting means volunteers shift from persuading voters to ensuring that supporters actually show up.

In downtown Flushing, Queens, Mr. Sliwa’s campaign appeared to be running the largest canvassing operation, complete with a tent, a huge poster with his headshot in a red beret and campaign representatives handing out fliers in Chinese. Nearby, members of the Working Families Party handed out leaflets for Mr. Mamdani, and a single man distributed low-tech printouts from “The Action Network Against Socialist Communism,” which advertised a slate of candidates including Mr. Cuomo.

Mr. Sliwa’s trademark red beret was also a major presence on the Upper West Side, where his supporters donned red berets and held signs with his name as he promenaded into the Museum of Natural History to cast a ballot for himself.

Late in the afternoon, nine canvassers left the campaign’s small satellite office in the Republican stronghold of Howard Beach, Queens. Inside, campaign tote bags, sweaters and literature were stacked in tall piles, and a cartoon printout on the wall showed Mr. Sliwa cast against the skyline in a cape looking toward a mock bat signal — with his iconic beret in place of the Batman symbol.

For Nick Spinelli, the office coordinator, and many of the canvassers he was organizing, it was their first mayoral campaign. Though generally supportive, many of the New Yorkers they approached seemed aware of Mr. Sliwa’s long odds. Mr. Spinelli and other canvassers told them Mr. Sliwa still had a chance to shock the world.

At one house, Joe LoPiccolo, a Fire Department employee, warmly greeted Mr. Spinelli.

“How’s it looking?” said Mr. LoPiccolo, 37. “Manhattan’s going to destroy us.”

Mr. Spinelli stayed upbeat.

“We’re trying to turn out every vote we can!” he declared.

Reporting was contributed by Nicholas Fandos, Tim Balk, Olivia Bensimon, Sarah Goodman, Alex Lemonides and Sarah Chatta.

Benjamin Oreskes is a reporter covering New York State politics and government for The Times.

Maya King is a Times reporter covering New York politics.

The post As New Yorkers Flood Early Voting Sites, Undecideds Become Prized Target appeared first on New York Times.