Anthony Jackson, a scholar and virtuoso of the electric bass who redefined his instrument while also laying down funky grooves for both pop stars like Madonna and jazz greats like Chick Corea, died on Oct. 19 on Staten Island. He was 73.

He had Parkinson’s disease and in recent years had suffered multiple strokes, his manager, Danette Albetta, wrote in announcing his death on social media. Bass magazine reported this year that health issues had prevented Mr. Jackson from performing since 2017.

In 2005, Modern Drummer magazine called Mr. Jackson “one of the most in-demand session musicians in the world” and described his opening riff on the O’Jays’ 1973 hit “For the Love of Money” as “one of the most memorable bass lines in popular music.”

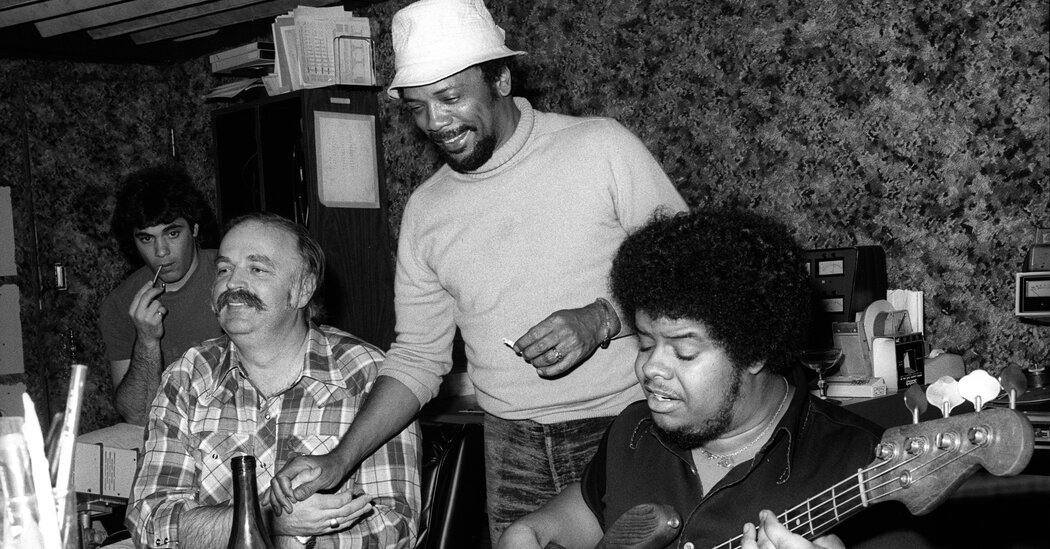

Mr. Jackson was a career sideman whose work ranged across many styles of jazz and pop. In just five years, he played on Quincy Jones’s cover of “Takin’ It to the Streets” (1978), Diana Ross’s “No One Gets the Prize” (1979), Paul Simon’s “Oh, Marion” (1980), Steely Dan’s “My Rival” (1980), Madonna’s “Borderline” (1983) and Luther Vandross’s cover of “A House Is Not a Home” (1983).

“I enjoy playing with a large ensemble,” he told Bass Player magazine in 2008, “and being the one to put a big, fat foundation under it.”

But one achievement of Mr. Jackson’s was clearly attributable to him above all: the invention of the six-string contrabass guitar — as opposed to the ordinary four-string electric bass — which introduced new range to the instrument.

“When it has been pointed out that I invented an instrument now played by thousands worldwide, it’s certainly a source of pride,” Mr. Jackson told Bass Player. “The contrabass guitar has been a path to ecstasy for me, my Eden.”

The first versions of the electric bass, also known as the bass guitar, date from about 90 years ago. The term “Fender bass” became widely used after Leo Fender introduced an electric bass in the early 1950s.

Shortly thereafter, record producers encouraged players of the upright bass to switch to the new sound — even though, Mr. Jackson often said, they considered the electric bass “a poor man’s upright.” As a result, he wound up being part of the first generation of musicians who trained on the electric bass first and devoted themselves, without condescension, to discovering its musical possibilities.

Mr. Jackson’s breakthrough was “For the Love of Money,” recorded when he was just 21 years old.

“It all started with Anthony Jackson’s bass line,” Joe Tarsia, the recording engineer at the session for that song, recalled to The Philadelphia Tribune in 2015. “I walk into the studio, and I heard this bending wah-wah on the bass. Nobody ever did that before, that I knew of.”

The song begins without singing and with Mr. Jackson’s bass the only instrument. His jaunty, not entirely predictable sound becomes the melodic hook. Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff, the songwriting and production duo, shared writing credit for the song with the little-known young bassist — something they rarely did.

“For the Love of Money” reached the Top 10 of the Billboard pop and R&B charts in 1974. It later became the theme song for “The Apprentice,” the reality show starring Donald Trump seen in various formats for more than a decade starting in 2004. In 2016, the track was chosen for the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Mr. Jackson dated the start of his mature style to his work on Chaka Khan’s 1980 album, “Naughty,” whose songs he told Bass Player in 1990 were “among the best examples of blatant commerciality infused with high art.”

Another measure of Mr. Jackson’s artistic self-realization came in his decades-long quest to invent a six-string contrabass guitar. At just 16 years old, he told Bass Player, he had already been playing the bass for four years and kept running into the same frustration: “wanting to get down underneath the bottom register and wanting to move to the upper register without feeling like I was going to run out of space.”

As soon as he began to make money, he searched for luthiers who could design a new type of bass. Initially, he encountered bafflement. He spent thousands of dollars commissioning instruments that he ultimately determined did not work. He tried homespun fixes using epoxy cement and serrated kitchen knives.

Then he found the instrument builders Vinny Fodera and Joey Lauricella. They made prototypes for Mr. Jackson that he tested for days on end. His heart raced when every new contrabass was done. With the 10th version, completed in 1996, “we hit the jackpot,” he said in 2008. It took another six years, Mr. Jackson said, for him to attain a deep understanding of how to play it.

In 2019, Bass magazine called that process “probably the longest and most productive partnership between a player and a builder in the history of the bass guitar.”

In 2008, Chris Jisi, an editor at Bass Player, wrote that histories of the five-string and six-string electric bass often portray them originating “magically and simultaneously from guitar companies in the early ’80s.” In fact, he continued, “the path to today’s easily accessed, wide assortment of 5’s and 6’s was forged largely by one musician, Anthony Jackson.”

Anthony Claiborne Jackson was born on June 23, 1952, in New York City. His mother bought him his first bass guitar, and he never forgot the details of the purchase: It was 1965, at Ben’s Music on West 48th Street, and the instrument cost $43.

The bassist James Jamerson, a mainstay of the Motown sound in the label’s early years, became his “mentor,” Mr. Jackson often said, based just on how closely he listened to him on recordings. He was also a devotee of organ compositions by Bach and Olivier Messiaen.

His last major regular work was with the Japanese jazz pianist Hiromi.

In March, the jazz fusion guitarist Al Di Meola wrote on social media that Ms. Albetta, Mr. Jackson’s manager, had become his caretaker, since he had “no family.” No information on survivors was available.

Though widely regarded as a master of his instrument, Mr. Jackson once told Bass Player, “There is no point where one can be said to have ‘mastered’ anything.” He preferred, he said, that “we remain seekers, never truly achieving our ultimate goals.”

Alex Traub is a reporter for The Times who writes obituaries.

The post Anthony Jackson, Master of the Electric Bass, Is Dead at 73 appeared first on New York Times.