For decades, heavy trucks roared past the traditional Malay homes, Chinese shophouses and British colonial buildings of Muar, Malaysia. They were part of the town’s economic engine, hauling away locally made wooden furniture like sofas and dining sets for export to America and other markets.

But the traffic has slowed dramatically in recent years. Muar, which Malaysia officially gave the moniker “Furniture City,” has been overtaken by rivals in China and Vietnam.

Now, there’s a fresh threat: American tariffs.

In August, President Trump imposed a 19 percent levy on most Malaysian imports. Last month, he threatened a much higher rate — as much as 50 percent — on items like kitchen cabinets and bathroom vanities, from any country, saying the imports were “unfair competition” for American companies. That sent shock waves through Muar.

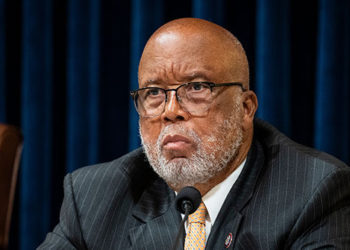

“I do not want Muar to be the next Detroit or the graveyard of furniture,” said Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman, Muar’s member of Parliament. “My biggest worry is that if we don’t negotiate with Mr. Trump well, Muar will be even worse affected.”

The highest levies are scheduled to take effect on Jan. 1, but Malaysian officials are hoping to reach a trade deal while Mr. Trump is in the capital, Kuala Lumpur, this weekend for a regional summit. Many U.S. customers have already paused furniture orders, said Desmond Tan, president of the Malaysian Furniture Council.

Sin Wee Seng Industries has been making recliners and upholstered sofas for more than half a century, sending its products to 50 countries. On a recent Wednesday, roughly 800 workers were on the job inside its fluorescent-lit Muar factory.

Rows of men and women sat hunched over sewing machines, while others assembled sofa frames. Coils of textile were piled alongside stacks of finished couches that were waiting to be wrapped, most of them bound for export.

Despite the buzz of activity, U.S. orders are down 30 percent since April, when Mr. Trump unveiled vast global tariffs, said Neo Chee Kiat, the firm’s managing director. He is betting that sales in Europe will help counter the decline.

“We feel stuck,” he said. “It’s unfair that the U.S. is targeting a small country like Malaysia, where most furniture makers are locals. Focus should be on places like Vietnam, where many factories are Chinese-owned.”

Bolstered by cheaper labor, Vietnam has become the second-largest exporter of furniture to the United States, after China. Last year, it exported more than $13.2 billion worth of furniture to America, nearly 10 times as much as Malaysia.

Most of Malaysia’s furniture exports come from Muar. Decades ago, the town’s furniture business was centered around a cluster of family-run carpentry shops. Government incentives helped bring in timber suppliers and component makers, paving the way for a multibillion-dollar industry that created tens of thousands of jobs at its peak.

Muar sits along the Malacca Strait, one of the world’s busiest maritime routes. But its coastline is too shallow for a deepwater port, and its factories’ output is trucked to ports two hours south.

In recent years, dozens of factories have shut down. Today, Muar has two modes: industrial by weekday, leisurely by weekend.

Tourists from Kuala Lumpur and Singapore stream in for its colonial streets. They stop in cafes by the Muar River for local specialties like asam pedas, a sour tamarind fish stew, and strips of otak-otak, a fish cake grilled in banana leaves.

“Our place is packed with tourists on weekends,” said Mohd Rizal, who manages a riverside cafe. “Weekdays are slow business because fewer locals come out to eat.”

Mr. Syed Saddiq, the lawmaker, said the town had lost its workweek buzz. “Now it’s just too silent,” he said. “Its eerie.”

Other manufacturers in town, like BSL Furniture, which makes bunk and loft beds for children, are being squeezed by price pressure from Chinese vendors, even if the U.S. furniture tariffs don’t directly affect them.

One company that dodged the blow from the Trump tariffs is Natural Signature, which makes wardrobes, bed frames and upholstered furniture. After Mr. Trump was elected last year, it shifted its focus toward Japan, shipping more of its products there.

“I just felt uncomfortable, and that feeling became my strategy,” said Candice Lim, the company’s founder.

Most of her peers weren’t as prescient. The industry is now split between those bracing for survival and those convinced that demand will return.

Home Styler Furniture is a Chinese- and Taiwanese-owned factory that exports kitchen cabinets to the United States. On a recent day, it was running at full tilt, with nearly a thousand workers sanding, painting and packaging cabinets at a 20-acre site in Muar. Its chief financial officer, Peiheng Tsai, said the tariffs would slow orders but insisted that American demand for its products would rebound.

But Steve Ong, the president of the Muar Furniture Association, had a warning: If business doesn’t improve, firms may start moving out of Malaysia to lower their manufacturing costs.

“I am not sure how long furniture makers can take the pressure,” he said.

The post A Furniture Town Reels From Trump’s Tariffs (and Braces for More) appeared first on New York Times.