When Stephan Smerk called Fairfax County Police Detective Melissa Wallace on Sept.7, 2023, she was shocked to hear what he had to say.

“He says, I’m at the police department to turn myself in,” Wallace told “48 Hours” correspondent Anne-Marie Green, in “Closing the Cold Case of Robin Lawrence,” airing Saturday, Oct. 25 at 10/9c on CBS and Paramount+. “And I said, turn yourself in for what?”

Smerk, a married 52-year-old father of two living in Niskayuna, New York, was calling to confess to the 30-year-old cold case murder of Robin Warr Lawrence.

“A million things start going through my mind,” Wallace said. “The adrenaline was pumping so hard because the reality hit … of what this means and that we’re getting ready to close this case.”

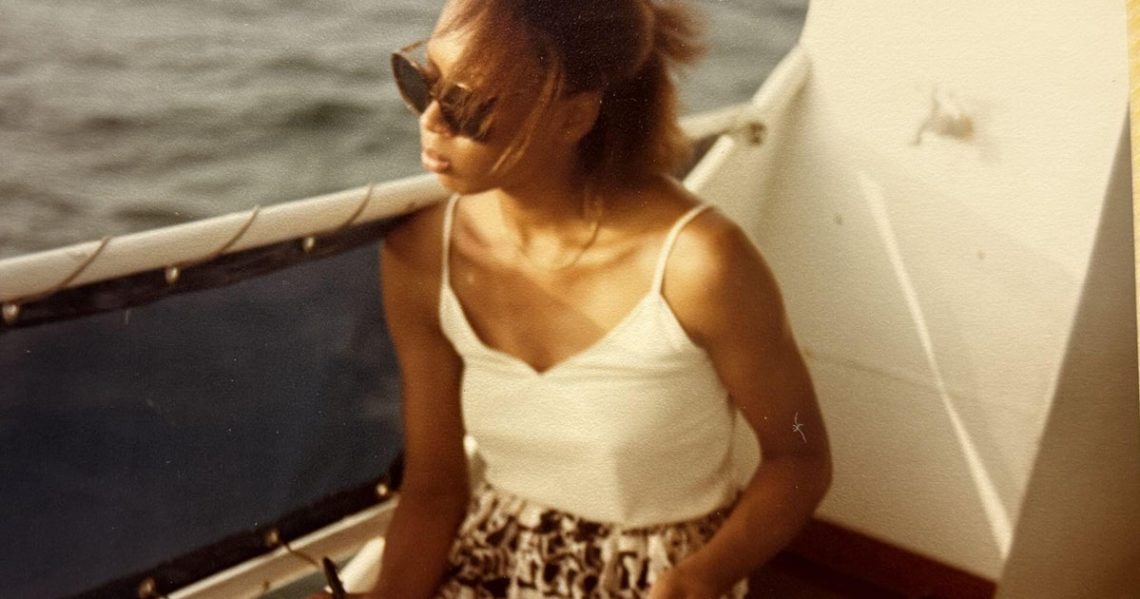

Robin Warr Lawrence, an artist and mother, was brutally murdered in her home in Springfield, Virginia, in 1994. For two days, her daughter Nicole, just 2 years old at the time, roamed the house alone before her mother’s body was discovered. And for three decades after that, detectives tried to figure out who could have done this to Robin.

“Who would do such a thing? Why?” said Mary Warr Cowans, Robin’s sister. “I remember thinking at the funeral, Robin’s killer could be in this room with us. We didn’t know.”

It took decades, but eventually the family would get their answers. DNA evidence — in the form of blood left on a washcloth — had been found at the crime scene back in 1994, and at the time it had turned up no matches when investigators ran it through CODIS — the FBI’s national database. Years went by and new techniques were developed, including a process called genetic genealogy.

In genetic genealogy, a suspect’s DNA is used to find their relatives. Then investigators research those relatives’ family trees until a potential person of interest is found — someone who would have been the right age and in the right place at the right time to commit the crime. Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA technology company that often works with law enforcement, did not have high hopes for solving Robin’s case using this technique because the database matches were very distant.

“Parabon gave us a solvability rate of zero on the case,” said Wallace.

Fairfax County Police Department volunteer Liz, who asked that her last name not be used, thought she’d take a crack at it anyway. The process proved difficult. “I was ready to give up a number of times,” Liz told “48 Hours.” “But I kept thinking, well, I’ll just finish this or just do this one more thing.”

After three years of doing just one more thing, Liz came up with a possible suspect. He’d lived in Virginia in 1994 and would have been around the right age to commit the murder. His name was Stephan Smerk.

“I wasn’t very hopeful at the time,” Wallace said. “I was just looking at this guy’s background. I’m thinking, there is no way.”

Smerk had a completely clean record, without so much as a speeding ticket. He worked as a computer programmer in suburban Niskayuna.

Though they had their doubts, Detectives Melissa Wallace and Jon Long took the trip up to Niskayuna to talk to Smerk. Their goal was to get his DNA, to see if he was related to the person who had left their DNA at the crime scene – or if he was that person.

“He comes to the door right away,” Wallace said. “All we said is we are detectives from Fairfax County, Virginia, and we’re looking into a cold case from the 90s.”

Smerk, detectives say, had no reaction. “Stone-faced,” said Long. Smerk gave his DNA willingly, and Wallace and Long went back to their hotel. Then Wallace got that call.

“I was freaking out,” Wallace said. “I run down to [Long’s] room, while I’m still on the phone, and I’m banging on his door, and he comes to the door, like, what is the problem? I’m like, we got to go to the police department.”

When they met Smerk at the Niskayuna Police Department, officers had taken him into custody and he was ready to talk. Wallace and Long sat him down in an interrogation room, and without much prompting, Smerk confessed to the murder of Robin Warr Lawrence. He had gone to Robin’s home that night in 1994, he told them, for no other reason than wanting to kill someone.

“I knew that I was going kill somebody,” Smerk told the detectives. “I did not know who I was going to kill.” At the time, Smerk was in the military and posted at a base nearby and was familiar with Robin Warr Lawrence’s neighborhood because a friend had stayed there. He said he had no idea who lived in Robin’s house.

“There could have been 50 people in that house. I don’t know. They could have all had guns and shot me dead. I wasn’t even thinking about that.” All Smerk was thinking about, he told detectives, was killing. He said he had compulsions that he couldn’t control.

“I honestly believe that if it wasn’t for my wife and my kids, I probably would be a serial killer,” Smerk said. “I am a serial killer who’s only killed once.”

“It’s such a shocking statement,” Wallace told “48 Hours.” “It makes no sense. You know, if you’re a serial killer, you don’t kill once. But, on the other hand, he was very candid and open and honest throughout the rest of the interview. So, it could be true that he has only killed one person.”

Is it possible for someone with the impulses of a serial killer to kill just once? Former FBI profiler Mary Ellen O’Toole says it can happen.

“We have learned over the years with cases like BTK and the Golden State Killer and other cases where they do stop,” she explained. “The compulsions don’t go away … they tell us that they rechannel it. They put it into a different activity. So that activity can be something that is less than murder, but it could involve, for example, Peeping Tom behavior, autoerotic behavior … but you don’t just cut those urges off. Something has to replace them.”

Smerk had zero incidents on his record. O’Toole says it’s possible he never committed another crime, but she doubts the ideas in his head went away. She said she’d like to know more about his ideation in order to determine whether he could be a threat in the future.

“That ideation that really led to the murder in the first place, that would be troubling to me until I knew a lot more about that. What triggered it? What are you doing with it now? Don’t tell me it’s never there. Don’t tell me that it just went out the window after you committed that murder.”

In his interview, Smerk expressed no remorse for what he had done. When asked if he had anything he’d like to tell Robin’s family, he replied, “How do I say this? I know you’re recording … I don’t feel anything for the family. …I feel bad that I did it because I knew someday my personal freedom would be affected.”

Smerk pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 70 years in prison. He will be eligible for parole in 2037, when he is 65. Robin’s family said they are glad to have closure as long as Smerk spends the rest of his life behind bars, but the consequences of his actions will never leave them.

“It helped to know that a person was found and being held responsible,” Warr Cowans said in her statement to the judge at Smerk’s sentencing, “but it didn’t help to know what he did to [Robin] and how she suffered … it doesn’t help and it doesn’t bring her back. She would have been in our lives for the past thirty years. But that was taken from us.”

She told “48 Hours” that for a long time she lived in fear, not knowing who had committed this horrible crime.

“I actually felt afraid at home, in my bed,” she said. “Thinking about someone just from out of the blue could show up from anywhere and kill you in your house … That’s just a scary thought that you’re not safe anywhere.”

“It’s scary,” echoed Long. “From a community perspective, that’s like your worst nightmare. Like, that’s the reason why you tell like your loved ones to make sure that your doors are locked at night. He is the boogeyman.”

The post Man confesses to cold case murder: “A serial killer who’s only killed once” appeared first on CBS News.