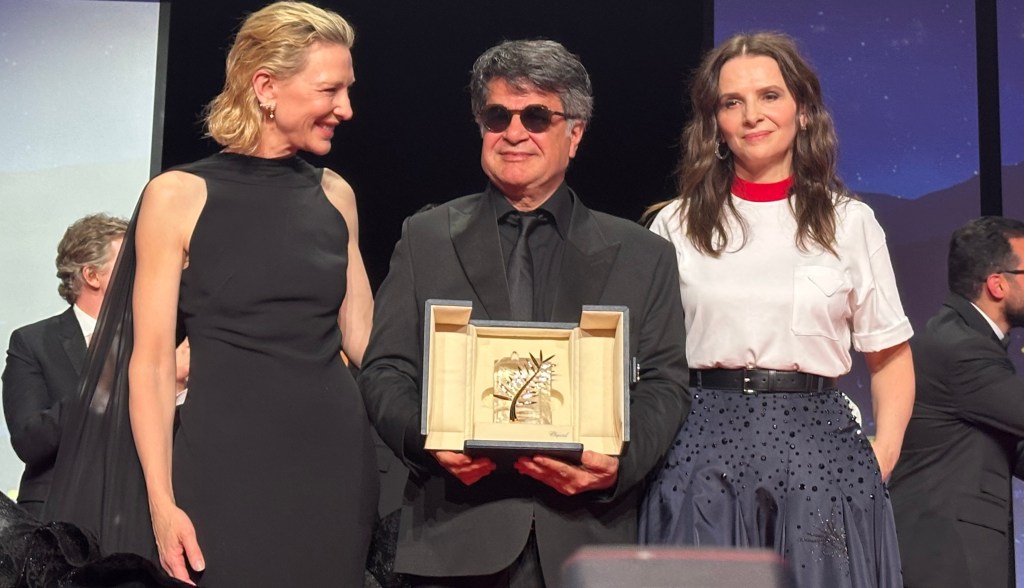

EXCLUSIVE: Jafar Panahi, director of Palme d’Or winner and France’s powerful official entry for the International Oscar, It Was Just an Accident, grins when we meet on Zoom. I tell him his smile reminds me of when I offered him congratulations at the Cannes closing night soirée not long after he’d been feted by the likes of jury president Juliette Binoche and presenter Cate Blanchett.

When I approached him at that Cannes party, Panahi was seated at a table on the beach, wearing dark glasses with the the golden trophy placed in front of him. How happy was he in that moment?

“My happiness at that moment goes back to something that happened the night before,” he says cheerily. But then his tone turns ominous when he adds, through interpreter Sheida Dayani, “That night before, I got a phone call from prison.”

That call was from Mehdi Mahmoudian, the Iranian political journalist and human rights campaigner who was incarcerated at the time because a comment he’d made about bedbugs in prisons had upset Iranian authorities.

Mahmoudian and other inmates had seen the impassioned speech the director had given at the Cannes world premiere screening of It Was Just an Accident in the Grand Théâtre Lumière, Panahi explained, saying, “It had made them very happy” and they were sure “something good” was going to happen on the last night in Cannes. The journalist, who has spent a decade in and out of jail, definitely had skin the game. He’d given some pointers to the film’s cast and crew about the intricacies of torture, and how it is be inflicted.

It Was Just An Accident follows Vahid, a garage mechanic, played by Vahid Mobasseri, who believes that the family man seeking help with his car is Eghbal, nicknamed Peg Leg, the government security officer who tortured him when he was jailed for speaking out for workers’ rights.

Eghbal is then kidnapped, locked in a wooden box, and loaded into a white van while Vahid seeks confirmation of his oppressor’s identity. And soon, a determined and motley crew sets out to test Vahid’s hunch.

Panahi says he knew what Mahmoudian meant by “something very good.” He realized that they’re waiting for the Palme d’Or.

“I kept saying that it’s not like every film is going to get it. We are one out of 22 films, and just our mere presence here is great. But he was like a soccer fan who could only think about winning, and he wouldn’t even be satisfied with the second prize, he wanted the first prize,” Panahi chuckles as his interpreter Sheida Dayani relays his words, as she did throughout the conversation.

After the phone conversation ended, Panahi went to bed but didn’t sleep well. “I was thinking to myself, ‘They’ve put me in a really bad place,’ because if I don’t win tomorrow, whatever happiness they had is going to turn into despair.”

Then, on the day of the closing ceremony, the power went out at Cannes “and you couldn’t even buy anything because the credit card machines didn’t work,” he laments. So, in that chaos, when the film’s delegation were summoned to attend the big closing shindig at the Palais — a sure sign they had been selected — Panahi and his daughter had only minutes to prepare. “I rushed into getting my clothes on and I just grabbed for my glasses and left.”

As he waited at the ceremony, all Panahi could feel was, he says, “this burden that they put on me the night before was really heavy.” But then his name was read aloud. “I just had a sigh of relief, and I realized that everyone around me is standing and clapping and I am lying back on my chair with a happy conscience.”

It seemed that burden had distracted him because, he says, “At the end of everything… I realized the whole night I’ve been wearing my wife’s glasses.”

As we dissolve into peals of laughter, Panahi declares that “I looked like a blind man. I couldn’t see, it didn’t matter what I saw and what I didn’t, what mattered was that the phone call I got, I had it behind me and I was done with that burden.”

Panahi says his friend, Mahmoudian was out of prison when he was writing the script and shooting, but was later jailed again. The director himself been jailed, twice, by the Islamic Republic and, at one point, was banned from making films in his homeland. It Was Just an Accident was a clandestine shoot following Panahi’s release from jail. He’d staged a hunger strike and was out within 48 hours.

The film — part chilling revenge thriller and part absurd slapstick — is riveting. There’s a moving moment of magnanimity, which won’t be given away here, that proves the underlying dignity of a people broken by an authoritarian state. Neon recently released the film in theaters in New York and Los Angeles. Mubi opens the picture in the UK on December 5.

I marvel at the many ways Panahi has used the art of cinema to expose the harsh restrictions the regime in Iran has imposed, on not just artists, journalists and activists, but anyone who dares speak out. And it’s increasingly happening in Western democracies also.

Panahi shrugs. ”Yes, it is what it is …And eventually you get used to it.” Sighing, he continues, ”But then you also get used to finding ways to say what you want to say. And in cinema, we still have been able to find a way to make films with all the limitations. And despite all these situations that you see, I made this film with the motivation of answering this question: ‘What happens in the future?’”

Arms outstretched, Panahi asks: “Is the cycle of violence going to continue in the future, or is it coming to an end at some point? That is when you can both speak and for any other reason, you won’t have these obstacles. What matters is to reach an understanding that you cannot delete violence with violence.”

His film reinforces that view, however it ends on a sinister, almost Hitchcockian note that will haunt both the character Vahid and the audience. And many living under authoritarian regimes know what that haunting feels like. “I don’t know if it was a conscious Hitchcock device,” Panahi says, “but this is a shared, lived experience in countries with authoritarian regimes. The individuals who cooperate with that system don’t matter. What matters is the system itself that is broken.”

The film was shot undercover without permission. Ahead of a recent screening in London, its producer Philippe Martin spoke to the audience about the high stakes involved in making the film in Iran, and how, towards the end of shooting, the set was actually raided.

The canny Pahani and his team were, however, prepared. “We have gained enough experience to make the film taking security measures, and making sure that it gets to the end of shooting. First, we started with sequences that would have less risk involved. Those would be sequences that were in the desert… or places where we did not gain a lot of attention. Eventually we made our way into the city, and again, we started with sequences that had the camera inside the car. And then we took the camera out of the car and we had to speed it up. And that’s when the problem started. When we shot an ATM scene, myself and a few other team members just got in the van and left to shoot something else, and that’s when we received a phone call saying that they have raided the scene,” he says, speaking breathlessly through the interpreter.

“We went and hid our equipment, and after we came back, we went on the set. We saw that there were about 15 plainclothes [officers] who have gathered around my team and are waiting for us. We were quite relaxed about it because there was nothing, no material, that they could get their hands on and create problems for us. It was also nighttime and they kept us waiting on the street for about four or five hours. When they saw that there’s nothing that they can get, they let us go.”

But then, the morning after, the police called some members of the production in for questioning. “They threatened them that they cannot continue working on this project” says Pahani. “I canceled work for about a month, and at the end I went with a much smaller crew and we had about two days of shooting left. We only shot the necessary scenes and we got out.”

Post-production was completed in Paris where the director has a residency permit. “The green screens we had shot in Iran and we did the post-production for them in Paris … It took us about three and a half months to do the mixing and the color correction.”

I ask Panahi about his sense of humor and how he juxtaposes scenes of almost slapstick comedy against backdrops of brutality. Was he a fan of Monty Python, perhaps?

“You really don’t have to look for it, the humor comes itself,” he says. Then he points to our earlier conversation. “I told you about that phone call and the glasses and all. Humor is in it. You don’t really have to do much. It’s just all part of the whole thing. And if I had to look for humor, you wouldn’t really believe the scenes that you were seeing as an audience. Both the believability and the tolerance of it would come down, so you would lose audience. Having said that, I did try to have humor until 20 minutes to the end of the film… The last 20 minutes become so heavy and striking that the audience cannot leave the theater without thinking about the film.”

It’s true. Such is the compelling power of Panahi’s film, I tell him that on both occasions that I’ve seen it, I’ve left the theater looking over my shoulder as I hurried down the street. And now I’ve made him laugh.

“I just work with my senses and with what I feel with my emotions,” he says. “I allow for my feelings and for a sense of realism to be flowing in the film. The audience does know that they’re watching fiction, but they’re constantly adapting themselves between realism and fiction, and this is how they can believe the story better,” he explains.

Also, I observe, it’s often through fiction that we understand the reality of the world.

“Exactly,” Panahi agrees. “Because anything real has a story itself, but it also matters how you look at a story. From what angle are you looking to make the realistic sense of it better, or stronger, does matter. Even the framing, even the editing, they all affect the sense of realism.”

He zeroes in on a key moment involving a scene where Eghbal has been bound to a tree by Vahid. It’s fascinating to hear the filmmaker break down a scene, and his analysis elucidates the complexity of thought that went into capturing Eghbal’s detention.

“Throughout the film you see characters talking about one person who is absent. He’s in a box, as if they don’t make room for him in their own image. Then I thought that now I have to have an image for him in which he won’t let others in. And this was my way of sticking to visual justice, as if this shot belongs to this person and is his share. This is while Vahid is walking around him, sometimes you see his feet, sometimes he sits down, but when he gets up, you’re not following Vahid. You’re concentrated on Eghbal,” Panahi says. “And this is to signal to the audience that we’re not having a partial view, that we have tried to stay impartial and we’ve tried to be fair and just to all the characters.”

It should have been the easiest part of shooting, but it proved to be a difficult shot to capture, he says, “because you’re dealing with an actor who is blindfolded, whose hands are tied, whose torso is tied to a tree and he doesn’t have any room to maneuver with.”

Everything has to show in Azizi’s face — the actor playing Eghbal. “Every moment of pause or silence. And every movement will affect his performance. We usually expect superstars to bring out the role of the supporting actor really well. But this actor, Ebrahim Azizi, is not a superstar, yet he has done so well,” says Panahi proudly, while also complimenting Mariam Afshari’s performance as Shiva, a photographer who might also have been abused by Eghbal.

Panahi contends that If this shot hadn’t come out well “the entire film would’ve been wasted. And I took this shot aware of this fact. I shot it one night and it didn’t come out well. No matter what I did, it was coming out fake.”

That’s when he reached out again to Mahmoudian. ”I asked him to come on the set because he has spent 10 years in jail [on and off] and he knows how these interrogators act. I asked him to give all the details to the actor and tell him when to have hysterical laughter, when to come down, when to show force, when to humiliate the other characters. He knows those very, very well.” The filmmaker smiles. “Just watch and see that there’s not even an extra second in it.”

There’s also a significant cultural observation made about the mandatory rule that Iranian women shield their faces with a veil. There are instances where the character Shiva is seen without the hijab. It’s powerful symbolism.

Pahani talks solemnly of the horrific assaults by the Iranian authorities on women who sought to overturn the hijab ruling. “A lot of people got killed, a lot of people got shot directly in the eye, and a lot of people paid a high price for this, meaning they were directly targeting the beauty of women. They were blinding them intentionally,” he says, shivering.

“They even would give financial fines to people if they sat without hijab in their cars. But you would see that the day after, women would go back on the streets, and it is now the case that you see women with and without head covering on the streets. If we were only going to show women with head covering, we were compromising the sense of realism in our work,” he suggests.

Panahi’s allowed to live in Iran, but travelling in support of It Was Just an Accident for Neon is often problematic because, he says, “I have to keep applying for visas. And either I am traveling or if I’m not, then my passport is held by different embassies, especially by the American embassy, because sometimes they take about 20 days, they hold my passport just to give a visa on it. And without my passport, I cannot travel to Iran.” He’s staying in the U.S. for now, due to the single-entry U.S. visa issue. “It’s very important and it is necessary for me to be here,” he says. But it means that he can’t travel freely elsewhere.

In Pahani’s 2006 award-winning comedy Offside, about the cruel cultural chains binding Iranian women, a group of young women attempt to gain entry to a stadium to watch a World Cup qualifying match between Iran and Japan. Check it out if you haven’t seen it.

I’m curious to know whether he’s a soccer fan. “To some degree,” he replies, seemingly delighted to have been asked. “When I was younger I loved it more, and that’s why I made Offside.”

I probe as to whether Pahani supports any premier league club, or a European one, for that matter.

As he relays his answer to Sheida Dayani, I catch the dreaded words, “Chelsea” and “Manchester.”

“I don’t know where you’re supporting, but yes, Chelsea and Manchester United,“ he says, as I childishly wave my arms chanting ”Arsenal, Arsenal”, while he considers my boorish football terrace behavior with apparent amusement .

Freedom is a wonderful thing. Please do see It Was Just An Accident in a theater if you doubt that statement, and certainly if you don’t.

The post ‘It Was Just An Accident’ Director Jafar Panahi On The Real-Life Torture And Oppression Behind The Film: “We Still Have Been Able To Find A Way” appeared first on Deadline.