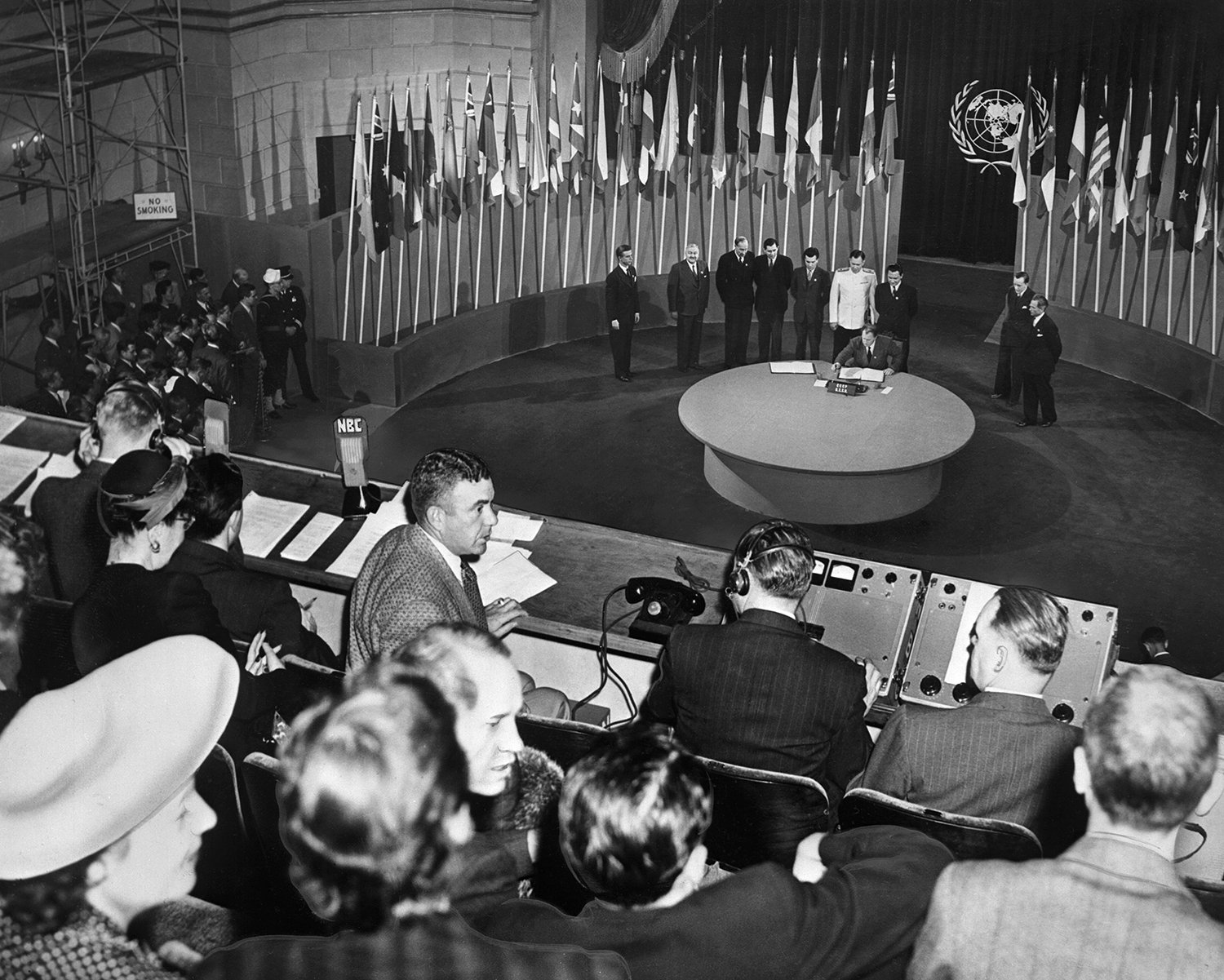

Exactly 80 years ago, on Oct. 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter entered into force. But the U.N. is limping through its birthday in a state of internal crisis. Confrontation and self-interest are on the rise in our dysfunctional family of nations. A global war is a significant risk; nuclear weapons holders are openly threatening their use; climate change is making parts of our world uninhabitable; and unregulated AI risks deepening socioeconomic inequality and threatening our cognitive security.

And yet, despite the seeming inability of our international systems to solve existential problems, the public still believes in global cooperation, and in the role of an institution like the U.N.

In a survey of 23,000 people in 18 countries, two-thirds said international decision-making is the most effective way to find solutions to future risks. Another new global poll of 36,000 people across 34 countries found that a majority (55 percent) want their country to work with others to take on common threats—even if it means compromising on some national interests.

While global support for international cooperation remains high, trust in the institutions that deliver it is notably weaker. In results of a new survey by Nira Data of 117,000 people around 101 countries, 73 percent of people who had an opinion about the U.N. said it needed reform. The view of the people mostly mirrors that of national governments.

Preserving the ideals and goals of the U.N. was a common theme at the recent U.N. General Assembly. A vast majority of national leaders’ speeches called for renewal of the U.N. for the benefit of their own people and the world in general. Our research shows that 78 percent of speeches mentioned the word “reform”; it featured more than references to climate change, Palestine, or Ukraine.

This means we have an opportunity. People and leaders want international cooperation—but they want it to work. And it’s important to remember that it once did.

As writer and historian Thant Myint-U, grandson of former U.N. Secretary-General U Thant, reminds us in his new book, Peacemaker, the U.N. has had periods of great success, including mediating conflicts like the Cuban missile crisis, and supporting the process of African decolonization.

“Storytelling matters,” Thant told me recently. “If we see the U.N. as an abstract idea in 1945 that has never really worked, it gives us no incentive to fix it.” So, if the U.N. has worked in the past (and in some arenas, still does), the question is how we can get it back to an effective role across the board today, fixing the problems others can’t tackle, in an arguably much more malignant environment for multilateralism than before.

The many ideas out there include laudable efforts to improve the process for selecting the U.N.’s secretary-general; to reduce duplication and bureaucracy within the U.N. (the UN80 Initiative); and to allocate Africa permanent seats on the U.N. Security Council.

But we need to be much more intentional about what kind of reform is needed to meet the moment. As the world order collapses before our eyes, a much more fundamental and ambitious reimagining is necessary.

At the recent opening session of the U.N. General Assembly, Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley argued, “We must find, first and foremost, whether we still agree on the values that inform our charter. As simple as this seems, this is necessary in any reset.” As a former special assistant to U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who went on to hold very senior positions in the U.N., told me, “I have never been so pessimistic about the U.N. We don’t have time for incrementalism anymore. It is reform or die now.”

The problem is that many of the ideas for U.N. reform currently on the table seek to address one of four things: structures (for example, mergers of U.N. agencies or Security Council membership); procedures, like how to streamline mandates; costs (namely, how to find savings); and culture (i.e., how the secretary-general can be bolder).

But they do not address the more underlying causes of the U.N.’s dysfunction that are baked into its very foundations: the veto power of five countries; the mismatch between the WWII worldview – in which national sovereignty reigns supreme – and our hyperlinked, interdependent present; a failure to adapt to a near-quadrupling of its membership; and environmental, technological, social, and commercial pressures unrecognizable to its creators. In addition, at a time when some companies have more power than states and popular movements can be more effective in driving change than national policy, there is still very little role for non-state actors in the world body.

The U.N.’s architecture and toolkits are based on an anachronistic vision of the world. Its rules were crafted before a nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, before the climate crisis, and before the advent of AI, and they privilege the winners of a war that ended almost a century ago.

One avenue for reform that can address these fundamental flaws—and enable other improvements to thrive—lies within the U.N. Charter itself.

Article 109 of the charter was included as a concession to the many countries opposed to the veto power of the permanent members of the Security Council: It provides for a conference to be held, if agreed by a majority of countries, to review and update the founding document of the U.N.

Many countries signed up to the U.N. project on the promise that within 10 years of its establishment, the distribution of power would be revisited. When, in 1955, a resolution to hold a charter review conference was proposed, a majority of countries supported the idea in principle, but thought they should wait for more “auspicious” circumstances.

Going back to first principles has until recently spooked many diplomats, but as we hit close to rock bottom, the idea is now gaining steam.

In calling for a renewed charter in her speech at the U.N. General Assembly, which she described as a “right” of younger generations, North Macedonian President Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova pointed to the need for a new social and natural contract (the word “environment” does not appear in the U.N. Charter) and more power for the General Assembly, where every country has an equal vote.

Kazakhstan’s president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, said now is the time to have a “serious conversation” about charter review, referring to outdated language like the labeling of Germany and Japan as “enemy states.” In a joint statement, Brazil, India, and South Africa also made the case for an Article 109 conference.

There is no shortage of ideas on what ought to change. Renewal of the U.N. Charter could lead to more equitable and effective global governance by limiting the scope and use of the veto; creating a Earth System Council to manage the climate and biodiversity crises in a more enforceable and less fragmented way; establishing a Parliamentary Assembly or standing U.N. Citizen’s Assembly to better engage the world’s citizens in global decision-making; and changing the secretary-general’s term to a single, longer term so that he or she can be more independent of member states. (Many more ideas are listed in this 2024 report.)

Any changes to the U.N. Charter will ultimately be for member states to negotiate and agree. What is necessary is a structured and inclusive process for a conversation about what the next world order should look like. This more ambitious approach to reform does carry risks, but they must be measured against the risks of maintaining the status quo: Countries go elsewhere to strike bilateral and so-called minilateral deals, creating a multipolarity that has no common anchor; the law of the jungle prevails; and the world becomes even more fragmented and dangerous with regular people paying the price.

Some diplomats worry that in the current polarized geopolitical context, reopening the charter could lead to something worse. But the threshold for any changes is high: They must be ratified by two-thirds of the world’s countries and all five of the permanent members of the Security Council to take effect. Recent intergovernmental negotiations, such as the U.N.’s Pact for the Future, agreed in September 2024, show that a majority of countries are still willing to fight for the principles on which the U.N. was founded.

A lack of evolution may carry even greater risks for the U.N. Kenyan President William Ruto put it bluntly: “Institutions rarely fail because they lack vision or ideals; more often, they drift into irrelevance when they do not adapt; when they hesitate to act; and when they lose legitimacy.”

Greater inclusion at the Security Council also has some human rights advocates worried that more seats at the table will mean more influence for authoritarian leaders. Here, Trita Parsi, executive vice president of the Quincy Institute, offers a compelling counter-argument: “Democracy is on retreat globally. … The way to fix that problem is not to rig the game when it comes to U.N. Security Council reform, but actually address the challenges that democracy is having here at home.” International law, Parsi says, cannot be contingent on your domestic political make-up. “International law treats all states as the same.”

But an existential question remains: A review conference might not be enough to save the U.N. if states are no longer committed to the values of the charter, such as sovereign equality, human rights, socioeconomic development, collective peace, and security. In fact, in that case, a review could spell its undoing. But as author and professor Amitav Acharya argues in his new book, The Once and Future World Order: Why Global Civilization Will Survive the Decline of the West, the principles that underpin multilateralism are universal, deeply rooted, and date back centuries. In particular, he notes that countries from the global south were active contributors to the post-WWII world order, including in areas of human rights, racial equality, and multilateralism.

And even if a disagreement on norms is exposed, charter review will clarify commitments and make states articulate where they stand. At the same time, with input from those countries absent in 1945 (only four African countries participated in the negotiations as most of the continent and nearly one-third of the world’s population was still under colonial rule), a revised U.N. Charter could generate buy-in as well as persuade reluctant or hostile states to adopt common principles. Either way, wouldn’t a more honest assessment of where alignment exists be better than a charter that has beautiful words on paper, but is routinely violated and ignored?

Possibly the likeliest risk of all is that the process leads to mundane outcomes that underwhelm and disappoint. But at least the international community will have built up the muscle of evolving its governance, and as the process is repeated, say, every 10 to 20 years, it can be more ambitious with every review.

In his memoir, Harry Truman, who was U.S. president when the U.N. Charter was adopted, wrote: “I knew many of the pitfalls and stumbling blocks we could encounter in setting up such an organization, but I also knew that in a world without such machinery we would be forever doomed to the fear of destruction. It was important for us to make a start, no matter how imperfect.”

Nothing is fixed: In 1945, leaders were bold and visionary in imagining a global organization to constrain their own power, in their own interest. They can do so again today.

The post For Its 80th Birthday, the U.N. Needs More Than a Reset appeared first on Foreign Policy.