Napoleon’s army was starving and freezing as it withdrew from the failed invasion of Russia in 1812. It was also stalked by additional killers: bacterial infections.

When a group of French researchers set out to answer which infectious diseases helped fell the troops, they did not have much to go on: only 13 teeth from men buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, Lithuania. They were among the doomed soldiers of an army dispatched by the French emperor that initially numbered around a half million.

But each tooth had a dollop of tissue and blood inside that contained tiny fragments of microbial DNA. Using state-of-the-art methods, the researchers found evidence of two kinds of bacteria that had not previously been suspected of circulating among these troops.

One is relapsing fever, an infection carried by lice that resembles typhus. Like that disease, it causes high fevers, joint pain, severe headaches, nausea and vomiting, and extreme fatigue.

The other is paratyphoid fever, transmitted through contaminated food or water. Its symptoms include a high fever, headache, weakness and abdominal pain.

Their paper was published on Friday in Current Biology.

While other infectious disease is also suspected in playing a role based on historical accounts, this study adds two more killers to the record.

“This is really good work,” said Kyle Harper, a historian at the University of Oklahoma who was not involved in the study.

And, he said, “it’s an interesting historical case study,” of what he called, “an extraordinary episode of human suffering.”

But Mary Fissell, a medical historian at Johns Hopkins University also not involved in the research, cautioned against drawing sweeping conclusions from a study of just 13 teeth.

The researchers who led the study agreed with her.

Nicolas Rascovan, an expert in ancient DNA at the Institut Pasteur in Paris and lead author of the new paper, said he by no means thought the two pathogens identified by his group were the sole cause of the demise of the troops.

Much more important, he said, was that the men were starving, dehydrated and freezing.

The men, he said, were tottering on the edge of life and death.

“In those conditions,” he added, “any infectious disease can kill people.”

The story of that ill-fated assault on Russia inspired Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” and has fascinated historians, who cite it with a sense of horror.

From the moment Napoleon’s army arrived in Moscow, things went horribly wrong. The troops found a city destroyed, on purpose. Muscovites had burned it down. There was no food, no other provisions. The French soldiers soon were “begging for a piece of bread, for linen or sheepskin, and, above all, for shoes,” according to one account.

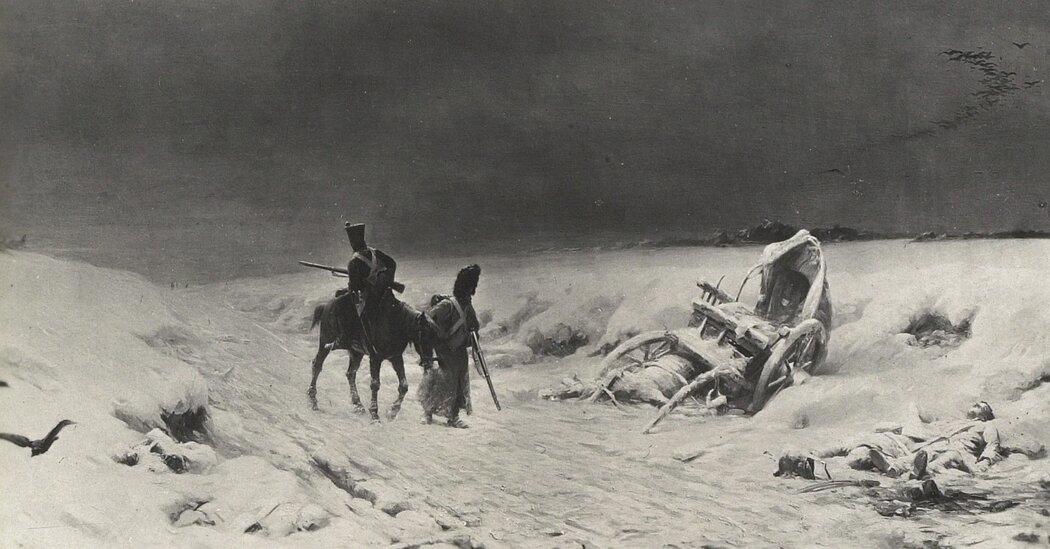

In October, Napoleon ordered a retreat. But the worst was yet to come for the already weakened men — a frigid winter and little food. The conditions were so harsh and so debilitating that diseases that might ordinarily sicken but not kill could prove fatal. Ill soldiers died, collapsing along the frozen landscape.

A French physician who was present during the campaign, Dr. J.R.L. de Kirckhoff described the scene:

Soldiers unable to go further fell and resigned themselves to death, in that frightful state of despair which is caused by the total loss of moral and physical force, which was aggravated to the utmost by the sight of their comrades stretched lifeless on the snow. During a retreat so precipitate and fatal, in a country deprived of its resources, amid disorder and confusion, the sad physician was forced to remain an astonished spectator of evils he could not arrest, to which he could apply no remedy.

As for the diseases that afflicted the men, Dr. de Kirckhoff listed typhus, diarrhea, dysentery, fevers, pneumonia and jaundice.

In 2006, in an initial attempt to understand the nature of the men’s illnesses, a different group of researchers reported finding segments of body lice in the soil of the mass grave in Vilnius. Three of the lice carried bacteria for trench fever, they wrote. They also reported finding typhus bacteria in the teeth of three men and trench fever in the teeth of seven. But the study was done when the technology for studying ancient DNA fragments was not well developed, making their findings less than definitive.

In the end, historians say, Dr. de Kirckhoff’s writings and today’s science point to the same conclusion: It was not wounds of battle that killed most of these men. It was starvation and frigid temperatures that set the stage for deaths from infectious diseases.

“The attrition of the army is extraordinary,” Dr. Harper said, “and underscores how much prior to the 20th century what we think of as wars are primarily medical events.”

The infections, he added, “are diseases that exploit human suffering.”

Gina Kolata reports on diseases and treatments, how treatments are discovered and tested, and how they affect people.

The post DNA Identifies 2 Bacterial Killers That Stalked Napoleon’s Army appeared first on New York Times.