Ten years ago, when I turned 40, my father posted a birthday message on my Facebook page that was visible to all of my friends and followers. I had a great life, he said: a loving wife, three beautiful children, a successful career. But all men’s lives fall apart at this age, he warned. He was 73 then, and was thinking of his own life and of his father’s. There is too much pressure and there are too many temptations, he said. He had entered a spiral at 40 from which he never recovered. He hoped the same would not happen to me.

I read the post, puzzled. It was a private note in a very public place. I responded with humor and deflection, but it made me realize something. My father’s old friends always said that I remind them of him. I had spent much of my life trying to be like him: going to the same schools, traveling to the same places, taking up the same hobbies, forever seeking his approval. But I also desperately wanted not to be like him. I didn’t want my discipline to drop. I didn’t want my id to overcome my superego. I didn’t want my life to fall apart at 40.

Running seemed like it might be the key. Running had helped him hold things together until middle age. Then he had stopped. I had run with him for years, and I was still competing in marathons. I was going to keep on running, and I was going to keep doing it well.

People often told me that my father was unlike anyone they’d ever known. He’d grown up in Oklahoma and escaped an unhappy home by winning a scholarship at Phillips Academy Andover, another at Stanford, and then a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford. When he met John F. Kennedy in 1960, Kennedy joked that my father might make it to the White House before he did.

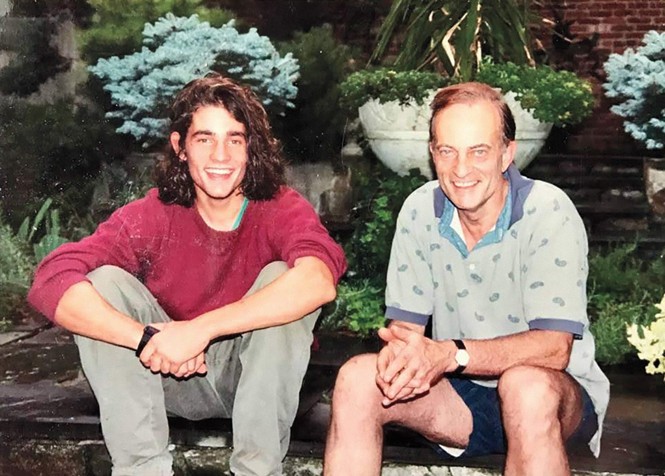

For all of his early promise, though, professional success didn’t come easily. He entered academia while dreaming of politics, but didn’t find satisfaction in the former or success in the latter. By the time I was born, in 1975, he was drinking too much, smoking too much, and worrying too much. Then he started to run. The great running boom of the 1970s had inspired him, and the sport offered discipline and structure to his ever more fermented days. When I was about 5, he’d head out in the mornings, and I liked to tag along when he would let me. Running a full mile made me feel as though I’d done something real. I remember proudly placing my tiny sneakers next to his by the front door of our house in suburban Boston. When I picture him now, I see him as he was then, strong and smiling, and running.

By the late 1970s, my father had earned a name as a young public intellectual and Cold War hawk. He won a White House fellowship and, for the next few years, traveled around the country for television appearances and debates. In one memorable exchange, he was debating arms control. His interlocutor declared that my father stood only for the Republican Party but that she stood for all of humanity. That may be true, my father responded, “but at least I have been delegated for my representation.”

Even as his professional stature rose, he battled alcoholism and gradually came to the realization that he was gay. He started a relationship with a 25-year-old male chemical engineer from MIT, and then one day he was gone, off to Washington, D.C. He got a job under President Ronald Reagan and started running even more, hoping to calm the chaos of his life. He ran every morning, alternating runs of 12 miles and six miles. When I visited him at his new home in Dupont Circle, he would head out on a run before I woke up and return, covered in sweat, just as I was making my way down his dusty, half-renovated stairway with its broken banister.

In 1982, he entered the New York City Marathon and headed to the start in Staten Island, where he sat and listened to Vivaldi’s Orlando Furioso on his Walkman. It was, he would later write, appropriate that he was listening to an opera about “a stirring figure driven mad by the world’s demands.” I was 7, and I came to watch him. I stood just past the Queensboro Bridge, where I handed my father a bottle of orange juice and a new pair of shoes. He finished in a hair over three hours. It was the fastest marathon he would ever run.

My father’s life in Washington was manic and confused, and he was entering a period of record-setting promiscuity and little sleep. He once told me that a person has the ability to resist the first affair in a relationship, but once the dam is broken, the waters flood out. The difference between zero and one affair is large; the difference between one and 100, he explained, is small. He began to date a string of inappropriate men, including a kleptomaniac who stole art from high-end auction houses, tried to poison my dog, and ran over my older sister’s cat. Not long after my father moved to Washington, he received the most traumatic news of his life. He visited a doctor, who pronounced that he was HIV-positive. “In a sense, I felt liberated,” he later wrote in his memoir. “The fit outcome of this interminable ordeal was to be not redemption but death.”

I was 10 years old when he told me that he was going to be dead within a year. We were in the car, just the two of us, on Interstate 66 in Virginia. I was sitting in the passenger seat, and I didn’t quite understand. I tried to laugh and tell him that yes, I knew everyone died, but he wasn’t going to. Still, he seemed sincere. He wanted me to know that he loved me and that I would be okay without him. I bottled the news deep inside. I never told anyone.

A year later, he enrolled in a study of healthy HIV-positive men. Shortly thereafter, he got a call from Anthony Fauci, the new director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, calmly saying that my father would be removed from the study because he didn’t have the disease after all. “We ran the test three ways,” Fauci told him. My father walked outside into the spring sunshine, elated and unsettled. A few weeks later, he told me that, actually, he was going to be fine. In later years, he would say that Fauci had “sentenced me to life.”

My two sisters and I would see our father once a week for dinner in Boston, and we’d travel to Washington, or to his farm in Warrenton, Virginia, for occasional weekend and summer trips. My father’s central project was to keep my sisters and me—but particularly me—from going soft. He worried that we would emerge from our suburban private school without calluses on our hands. He had left Oklahoma to join the New England elite. Now he wanted to put a little Oklahoma into his New England elitists. He gave us lists of chores at the farm—sweep the patio, mow the lawn—which he’d put on the fridge, and paid us 25 cents for finishing each one. He taught me to rotate the tires on a car and to drive a tractor. We dug huge firepits to burn our garbage and spent weeks planting poplar trees along the driveway. My sisters and I painted all the rooms in the house. Every summer, we stained the outdoor porch and pulled out the nails that had popped up in the Virginia humidity. Every now and then, my father and I would put on our worn-out sneakers, yell for the dogs, and run a mile or two down the Virginia roads.

My father often talked about momentum in life. Sometimes you have it: Each success makes the next a little easier and a little more likely. Sometimes you don’t, and your losses compound. When you have it, he would tell me, keep it and use it. Focus. Get more done. When you don’t have it, he’d say, well, try to get it back. I think of this frequently when I head out for a run. To have run during a day is to have at least done that. As my father descended into mania, the days when he ran were the days he kept everything else in control. If he had run more, could he have done more? When I was a child, there were days when I woke up and wished he hadn’t already put on his sneakers and left the house. Now, looking back, I wish he had kept doing it for longer.

When I was in my 20s, I tried to accomplish my father’s goal of running a marathon in less than three hours—but I had no idea how to do it. I signed up for five, started four, completed three, and came within half an hour of my goal in two. In only one did I run the entire way, without slowing down to walk. In the 2003 New York City Marathon, I dropped out at mile 23. My knee hurt. But something always hurts that late in a marathon. I quit because I was afraid to fail, and my knee gave me an excuse. It turned out to be the only time my father came to one of my marathons, and I gave up.

Around that time, my professional life was the same goat rodeo as my running. I had fallen in love with journalism, but journalism hadn’t fallen in love with me. In 1997, I was fired less than an hour into my first job, as an associate producer at 60 Minutes, because a senior executive decided I didn’t have enough experience and shouldn’t have been hired in the first place. By 2004, I was stuck in a different kind of rut. My wife, Danielle, and I were living in New York. I had been rejected from dozens of full-time jobs and was struggling as a freelancer. I took assignments that required waking up at 2 a.m., and earned a couple hundred dollars a day playing guitar on the platforms of the L train. My worst moment came when I submitted a guest essay to the Washington Monthly. An editor sent me helpful feedback but mistakenly included an email chain that I wasn’t meant to see. One of my closest friends in the industry had written a scathing assessment both of the story and of my general abilities. Maybe I just wasn’t good enough? I applied to law school and was admitted to NYU. I needed something new.

All the while, I kept running. In May 2005, I entered the Delaware Marathon. This time I did it right. I started out at a 6:45-per-mile pace and stayed steady as the course looped through downtown Wilmington. Even with a mile to go, I was terrified that I would fail: that my hips would freeze, that my knees would buckle, that my calf would tear. Repeated failure is both a motivator and a demon. In this case, it drove me forward. Soon I could see the finish line and the race clock, with the seconds ticking up from 2:57. For eight years, I had held in my mind the goal of breaking three hours. Now I had done it.

When running was going right, the rest of my life seemed to follow. In the months after Delaware, I got a job as an editor at Wired and scrapped the idea of law school. I wrote and sold a proposal for a book. I had momentum. In November 2005, I ran the New York City Marathon in 2:43:51, putting me in 146th place out of 37,000 entrants. I was starting to understand hard training. I figured I would keep going and get faster still.

Two weeks after that marathon, I saw my doctor for my annual physical. He took the usual measurements and ran through the usual routine. Then he put his fingers on my throat to check for lumps. He lingered a little longer than normal on one spot. “There’s something there,” he said. He told me that the lump could be completely benign, but there was a chance it might not be. I didn’t worry much. I had just run a fast marathon. I had always eaten a lot of spinach and hydrated well. I had many insecurities, but my health was not one of them. I was only 30, after all.

Gradually, though, the prognosis darkened. I traveled through hospitals for tests in blue gowns, each time certain that the next result would vindicate my assumption that the lump was just a benign biological blip. But each test result only made my odds worse. Eventually, the doctors determined that the sole option was surgery. My mother came to New York, and she and Danielle took me to NYU’s Tisch Hospital.

My father was not there that day. Stress made him short-circuit. He couldn’t talk about the possibility of cancer, and he certainly couldn’t offer any help. He started drinking more and writing me less. He later told me that he had become convinced that I would die. My mother, meanwhile, had never been more in control. She could be overwhelmed by small voltage shifts or tiny bits of stress—like making sure someone had put the potatoes in the oven on time. Actual catastrophes, like my illness, seemed to make her calmer. I think my mother could have been an excellent marathoner.

After the surgery, I felt nauseated, and I wasn’t allowed to exercise for three weeks. I had a scar resembling a necklace, which I’ll have as a marker for the rest of my life. My neck felt out of balance, like I was a strawberry with the stem partly cut off. I waited a week for the lab results. Then one day, I got the call. The tumor was benign. Two weeks later, I got a second phone call: The first group of doctors had read the slide wrong, and a review team had determined that I had thyroid cancer. It was an eminently treatable variant, with a survival rate of more than 90 percent. But it was still cancer.

In short order, I would need a second surgery to get the rest of the thyroid out. My neck already felt vulnerable. Now they would have to cut again. My mother came down for this surgery, too. After the second operation, I was miserable. Without my thyroid, I was dizzy constantly and couldn’t regulate my temperature. I felt cold when others felt warm. My tendons hurt. I got headaches all the time. And I had to prepare for a radiation treatment.

I bicycled to the hospital in Midtown Manhattan, where I was given a radioactive pill to swallow. It felt oddly normal for such a grave circumstance—like taking a multivitamin that came packed in an imposing lead container. But once I had swallowed it, I was a moving radiation site. I had to leave quickly, get on my bicycle, and try to stay as far away as possible from everyone else as I pedaled back home to Brooklyn. Danielle moved in with friends. Every day, she would come by our apartment and drop off soup for me at the door. I spent a week alone as the radiation moved through my body, hunting down the cancerous cells. I tried to stay calm and I kept doing my job at Wired, editing stories by email. But I wasn’t just dealing with pain; I was confronting death in a way that I hadn’t had to before.

We all, of course, are dying every day. However you do the math, we aren’t around for very long. But as I sat alone in our one-bedroom apartment, with radiation ripping my body apart, death was no longer just an intellectual exercise. Five months earlier, I had been a sub-elite marathoner; now, as I lay in agony on our red rug, I felt like that man had melted. I had been torn apart, and it was all because of a cluster of cells I could neither see nor feel. The week of isolation ended, though, as I knew it would. It felt like the winter solstice: The evenings were still dark, but now every day would get lighter. I deep-cleaned the apartment with the windows wide open and Danielle came back. More scans made clear that the cancer was gone. Now I could begin the process of recovering.

My diagnosis had come right after my triumphant marathon, and I believed that the only way to put it in the past was to run again. Odysseus had to string his old bow and fire an arrow through 12 axe heads to prove that he was the man he had once been. I needed to run another marathon.

I gradually started to train. My new medications made me perpetually dizzy, and I had to progress slowly from walking to bicycling to running. I had lost my strength and some of my coordination. My body had once seemed like a finely tuned instrument; now it would sometimes slide wildly out of key. I’d run two miles into Prospect Park and start to see double. I’d stop, and trudge slowly back. But I kept progressing. I got stronger, and I began to remember what it felt like to go fast.

As I healed, cancer went from the only thing I thought about to something I thought about once a day, and then to something I could put to the side. When I did come back to it, I was often running.

Two years later, in November 2007, I was back on the starting line of the New York City Marathon. The announcer called out, “On your marks.” I tensed out of habit and leaned forward, putting my weight on my toes. I crossed myself as a reminder that what I was about to do was both spiritual and quite hard. Then the gun fired. Across the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge we went, looking left to see the skyscrapers of downtown Manhattan. The bridge swayed ever so slightly as the mass of runners began to storm across.

With each step, I tried to visualize a different part of my body, moving with strength and relaxation. I thought about my toes pressing through my soft socks, onto the foam of my racing shoes, onto the hard asphalt, and then pushing me off. I marveled, as I often do, about how strange it is that one spends roughly half of each race suspended in the air.

After 44 minutes, I neared my favorite spot of the whole race: mile seven, where Danielle would emerge from Union Street in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Several blocks before that, I moved out of my pack to the right side of the road so that she’d be able to spot me. She stepped out of the crowd, and I stepped toward her and kissed her on the cheek. I thought back to two years earlier, when she had waited at the very same spot as I ran toward her with an unknown poison growing in my neck.

Later in the race, as I crossed from Queens to Manhattan, I spotted the exact place where I had stood in 1982, searching for my father in the sea of runners. I remember watching him swing out of the pack toward me. I remember the sweat on his hairy shoulders, and I remember a sense of love that emanated from him as he bent down on one knee, almost in prayer, tying the knots of the shoes I had given him.

By the time I hit mile 21 and entered Harlem, I had to fight with myself to keep going. Running with speed isn’t just a physiological process; it’s a psychological one. You have to remember what it feels like to pump your arms and legs in sync at a rapid cadence. You have to remember how to make yourself run up the hill that you don’t want to run up anymore. I had spent years learning these skills, and then a clump of cells in my neck had forced me to learn them again.

The course enters Central Park at East 90th Street, just before the marker for mile 24. By now my mind was almost empty. Finally, I saw the finish. I started to sprint as best I could. We get through most days in life without having to really think about death, which also means that we don’t spend a lot of time dwelling on the remarkable fact that we are alive.

That day, I ran the New York City Marathon in 2:43:38—13 seconds faster than I had run it before I got sick. I cried at the finish line. Later, as I headed down to the train that would take me home, an elderly man asked how I had done. “I did great,” I responded with a smile. He nodded, and I had a sense that he understood precisely what I meant: that I had pushed through something terrifying in life and come out on the other side just a bit stronger. I got onto the train and began the trip home, heading south under the city while above me thousands of marathon runners were still heading north toward the finish line.

By the time I ran my next marathon, I was a father. In just a few years, Danielle and I had three sons. Being a parent led me to discover what I consider the ideal form of cross-training. I wrestled constantly with my boys. We played so much hallway soccer that we chipped all the paint off the inside of the apartment’s front door. We played Nerf basketball, in which I could block shots only with my head. Each summer, up in the Catskills, we played “water wars,” in which I would try to swim across a pond and get up on a small beach they were guarding.

We created endless mayhem in our Brooklyn apartment. We broke vases, knocked over plants, and occasionally woke up the neighbors. But we had a lot of fun. And for 10 years I kept marathoning, and never once missed a workout or a race because of injury. I ran the New York City Marathon almost every year, and almost every year, I finished just around 2:43.

My father moved to Asia in the 2000s. He had an academic interest in the region and an attraction to the young men who lived there. He also wanted to avoid the tax authorities in the United States, who had noticed that he hadn’t paid his returns in several years. But he came to Brooklyn to visit soon after our oldest son, Ellis, was born, and I was startled both by his obvious love and admiration for his grandchild and by his total incompetence. He didn’t know how to hold a baby: Trying to hoist Ellis, he looked like a man attempting to lift a greasy turkey from the fridge. He had no idea how to change a diaper, making me suspect that he had never changed mine.

He came back when the other two boys arrived, brimming with love and carting chaos. He’d say he had to step outside to buy aspirin, and then I’d find him smoking and slugging gin and orange juice on the front stoop. One morning, sitting in our apartment overlooking Grand Army Plaza, with piles of his papers tossed upon our dinner table, he told me that his iPad had crashed and that he needed me to fix it. I rebooted it, only to discover that he had been trying to schedule time with a male prostitute in our guest room after Danielle and I headed out for work. It hadn’t occurred to my dad that the children, and their nanny, would still be there. I told him that I’d fixed the device but that he really shouldn’t do the thing he’d just been doing. He declared that he hadn’t been doing anything at all except working on an op-ed for The Jakarta Post. I walked down the stairs and told the doorman to not let anyone in while I was gone. That night, I balanced a chair against my father’s door in such a way that it would clatter if he headed out.

In 2013, my father planned a visit that coincided with the Brooklyn Marathon, a race of eight loops around Prospect Park that I had signed up to run. I had practically begged him to come to watch—I desperately wanted him to see me run fast at least once. But he didn’t make it in time. He showed up that afternoon, as I hobbled around the apartment with my aching post-marathon quads. He, too, was struggling to walk, having just had an operation on one of his hips. He told me that his struggles reminded him how important it is to remember a child’s first steps. This time I put him in an Airbnb in a fancy building on Prospect Park West. It seemed like a success, and the host was delighted to have such a smart and worldly man in the apartment. On the final morning, though, I came to pick my father up, and he hurried out the door. He had become incontinent during the night, wasn’t quite sure what had happened, and wanted to get out fast. I sent an extra-large tip.

My father would never see me run another marathon, but my children would. Each year, they would come and cheer me on as I raced the New York City Marathon. I don’t know what they’ll think of marathoners when they’ve moved out or when I’m gone. I hope, though, that one day in the future, in whichever cities they live, they stand on the sidelines of a major race, watching the runners flow by, remembering cold November mornings from a generation ago when their father, then strong and quick, ran by. I hope, too, that maybe they have absorbed some of the things that I’ve learned from training. As young children, they didn’t really have a sense of the way I did my job as a journalist or a CEO. Physical work made much more sense. They could see how tired I was after a workout, and they could appreciate what it meant to have run 20 miles before breakfast.

At the same time, I have worried over the years about whether my running detracts from my family and my work. Every now and then, I think I should take all my racing shoes and lock them in the attic. Running can be selfish and a waste of time. I couldn’t be the perfect parent, or the perfect CEO, even if I had 25 hours in a day. How can I possibly hope to be so if I only really have 23?

There are days when my running annoys my wife, my children, or my colleagues. I’ve accidentally woken up Danielle far too many times while heading out the door in the morning. The list of minor infractions is long. We basically have a deal. I try my best to make my obsession as minimally disruptive as possible. She rolls with the disruption and knows that I’ll make it up to her in other ways. And she also knows that running has become an essential part of my life. It’s the part of my day when I disconnect from screens and let my mind drift usefully and turn over problems. It encourages simple habits—healthy sleep, healthy eating, moderate drinking—that help me improve as a father and business leader just as much as they help me improve as a runner. Running has taught me to have total trust in the compound interest gained from steady day-by-day work. I got fast by running hard, consistently, and wasting very little time worrying about how ambitious my goals were. One lesson I learned about running that also applies to writing: The best time to do something important is usually right now. And when you have to get something done in a short amount of time, it’s wise not to spend that time complaining about how little time you have.

I learned, through practice, how to stay calm under stress. There were some deeper lessons, too. To improve at running, you have to make yourself uncomfortable and push yourself to go at speeds that seem too fast. The same is true in a complicated job. Our minds create limits for us when we’re afraid of failure, not because it’s actually time to slow down or stop. Which has done more to shape my mind: running or work? I don’t know. But I do think that those two parts of my life are now deeply intertwined.

In 2016, my father sent me an email while feeling particularly depressed. He wrote, “I’m in a corner, No Exit.” This was a hard time in my father’s life. He was 74 years old. His hands were cragged and bent from arthritis and years hunched over a keyboard. His liver was worn out from decades of overuse. He had lost most of his hair and dyed the last tufts an odd shade of rusty red. His teeth were rotting; his toenails were mostly black. If he wanted to walk for any distance, he had to do it in a pool. One day, he found himself sitting in his car for 30 minutes struggling to breathe. He was living in Bali, and that night, at 3 a.m. his time, he sent me another email, with the header “Saying thanks in the twilight zone.”

He wanted to tell me how much he had loved spending time with me in my 20s, and to apologize for some of his behavior then. I read the email more in sorrow than in fear. He often talked about premonitions of the end. I was used to the drama. I responded quickly with a photograph of my three boys eating chips and guacamole. In another gloomy email, he wrote that he was thinking back to me running with him in Boston: “Memories keep coming back, old age. Little boy joining me last half km of jog.”

Around this time, he wrote me that he needed a $1,500 loan to cover hotel expenses in Malaysia. He’d been charged double for a flight he took and there was some complexity involving a new boyfriend. He had some art he could sell, he claimed, and he promised to pay me back soon with interest. I knew he wouldn’t, and I was frustrated. I told him, perhaps too coldly, that I didn’t feel comfortable being a lender of last resort. I suspected that the problem wasn’t the price of the hotel but rather the price of the man. He immediately wrote to my older sister, cc’ing me, and declared that he was cutting me out of his will and that suicide was at hand. He said that he had already taken the pills. His death, he wrote, “will give all of you a sigh of relief, one in particular.” In another email, he told my sister and me: “May you find as much happiness as I’ve enjoyed in recent years.” I called him and then paid the hotel bill. Soon everything was fine, and he was sending cheerful emails again. The hotel, he noted, had a very cool book on guitars. It wasn’t the only time he threatened to kill himself to wrangle some money out of me.

When my father died of a heart attack the next year, my sisters and I traveled to the Philippines for his funeral. I put on my running shoes and headed up the hill above the villa where he had been living. Batangas is a tough place to run: The roads don’t have shoulders; there are dogs everywhere; jitneys screech by. That day, it was 90 degrees and humid. But I take pride in being able to run anywhere, and I wanted to understand this place and what he’d seen there. I moved slowly up, past Banga Elementary School. Then I stopped. I wondered how far I was from the antipodal point of the planet from where my father had grown up. If he had started digging a hole as a child in Oklahoma and gone all the way to the other side of the Earth, how far would he have ended up from here?

I jogged back down to the house. Some of his friends from around the world had flown in, and soon it was time for the ceremony. He had always loved music, so I brought out my guitar and played a short song I had composed for him. We all toasted his life, and the theme was similar whether expressed by the Filipinos, the Americans, or the Europeans: No one had ever known anyone quite like Scott Thompson.

I run about 3,000 miles a year, and it takes about eight hours out of every week. In recent years, I’ve moved beyond the marathons and begun running ultras: racing deep into the mountains, starting in the darkness and then trying to finish before the sun goes down. I’ve gotten faster with age, too. In my mid-40s, I dropped my marathon time to 2:29. In 2021, I set the American record for men my age in the 50K. In April, I ran the fastest 50-mile time in the world this year for anyone over the age of 45.

When you train seriously as a runner, you realize two wonderful things: You can’t get faster by magic, and you do get faster with effort. There are ways to optimize and to train smarter. And there are times when you work and work and don’t get the result you want. But really, to get faster, particularly in a long race like a marathon, you have to go out every day and run—even when you’re sore, tired, cold, grumpy, busy, or all of the above. You have to run when you have aches, blisters, cramps, diarrhea, exhaustion, fasciitis, grogginess, headaches, ingrown toenails, jock itch, knee pain, lightheadedness, myalgia, numbness, overheating, panic, queasiness, rashes, swelling, toothaches, unhappiness, vomit, wounds, and xanthomas. You may have to run through swarms of yellow jackets, and you definitely have to run when you’re zonked.

You have to learn to enjoy the pain. You have to convince yourself over and over that the goal is worth the struggle. You have to run when you don’t want to, and you have to do the extra loop around the lake when everything is telling you to go back home. You have to believe in the process. You have to believe that brick by brick, run by run, your body and mind are getting stronger. You have to believe this on days when you run slower than you did the week before. And if you want to run faster than you did before, you have to strain your body more than you did before. You have to build resilience so you can push yourself even more the next time you run. You have to search for that mystical sensation—the crux of this sport—where pleasure and pain blur into one. When you get there, pain means progress and progress means pleasure.

There are a lot of reasons I run. I like the mental space it gives me. I like setting goals and trying to meet them. I like the feeling of my feet hitting the ground and the wind in my hair. I like to remember that I’m still alive, and that I survived my cancer. I think it makes me better at my job. But really I run because of my father. Running connects me to my father, reminds me of my father, and gives me a way to avoid becoming my father. My father led a deeply complicated and broken life. But he gave me many things, including the gift of running—a gift that opens the world to anyone who accepts it.

This essay was adapted from Nicholas Thompson’s new book, The Running Ground. It appears in the December 2025 print edition with the headline “Why I Run.”

The post Why I Run appeared first on The Atlantic.