“You can smell human agony inside of the McDonald’s there. Fentanyl smoke, a distinct odor of burning SOLO Cups mixed with scorched marshmallows, an evil scent that signals suffering is nearby. ‘War Zone’ smokers have unmistakable vocal tics: anxious spit swallows from inhaling plumes of glass [crystal meth], deep croaking from opioid-aluminum lined lungs… Still, credit where it’s due: many… are working towards sobriety. An important milestone is quitting fentanyl, tapering down to heroin.”

Frank Blazquez says it’s his duty to seize what’s in front of him “before it vanishes.” Born and raised in Chicago, the self-taught photographer relocated to New Mexico in 2010 in search of a clean slate. An optician by trade, he took a job in Albuquerque and fell in with a sober crowd, intending to break the cycle of partying and excessive drug-taking that had enveloped him in Illinois.

It wasn’t long before Frank became drawn to Albuquerque’s “War Zone”—a neighborhood permeated by hard drugs, juvenile crime, and street violence—where his old ways caught up with him. Opiates, this time. By day, he worked at the optometry office. By night, he hung out and sold Oxycontin near Central Avenue and Louisiana Boulevard; “the War Zone nucleus.”

Eventually, these two worlds collided, and Frank lost his job. When he got clean again in 2016 he enrolled at the University of New Mexico, majoring in history. Meanwhile, inspired by fellow addicts and their desire to get clean and start a new life for themselves, he began making portraits of people in the area by way of telling their stories. His work, which has been widely exhibited and displayed in the Smithsonian, is a series of love stories as much as anything else, offering a blunt but empathetic perspective on life in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Las Cruces, Roswell, Chaparral, Artesia, Grants—places along the U.S.-Mexico border, where suffering and beauty, hardship and resilience, go hand in hand.

We caught up with Frank to talk about documenting the “War Zone,” what it’s like capturing the rhythm of lives dictated by fentanyl and meth as a recovering addict, and the impact of recent ICE raids on communities in New Mexico.

VICE: Your say your work provides “counter-narratives” of New Mexico. What aspects of it would you like people to see through your photos?

Frank Blazquez: I witnessed the power of counter-narratives at the Smithsonian, images challenging the status quo. As a recovering opiate addict, seeing a photograph I made in Belen, New Mexico—a town of 7,000—hanging next to a portrait of Donald Trump was proof that images can equalize, that the margins can stand eye to eye with authority.

On expectations, I respect audience feedback, but I’d rather focus on my perspective, what I want to see through them. For me, it’s essential to reveal insulated pain, the fatigue of routine and memorials that hold people together. I want to capture anticipation, the strange suspension of time that hangs over these lives. My work isn’t here to entertain, seizing what’s in front of me before it vanishes is the mission.

A lot of your photos are of people living in Albuquerque’s “War Zone.” How would you describe it?

The War Zone is in southeast Albuquerque. Violent robberies occur there frequently. Historically, the presence of blues describes it best. Blues are oxycodone pills. Now they’ve transformed into fentanyl pills and are almost extinct as its evolved powder form has arrived. Residents are accustomed to seeing body bags on asphalt, usually the victims of overdose. Burglar bar windows, slumping adobe motels, shockwaves of gunfire at night. Above it all, the Sandia Mountains press against the sky, crowned in pink light at sunset.

What’s daily life like for people there?

Fentanyl powder and crystal methamphetamine. They dictate everything. You can smell human agony inside of the McDonald’s there. Fentanyl smoke, a distinct odor of burning SOLO Cups mixed with scorched marshmallows, an evil scent that signals suffering is nearby. War Zone smokers have unmistakable vocal tics: anxious spit swallows from inhaling plumes of glass, deep croaking from opioid-aluminium lined lungs. Since the pandemic, most users chase the impossible. Smoking shards and opiate abuse—comorbidities of an addict, a combo that makes sobriety unattainable. Beating opiates alone is a 100-to-1 shot, but then they have to win back-to-back championships and do it all over again with meth.

Still, credit where it’s due: many War Zone drug users are working towards sobriety. An important milestone is quitting fentanyl, tapering down to heroin. I heard this in a conversation at a War Zone gas station: “Congratulations, I heard you quit blues [fentanyl] and only shoot black [heroin] now!”

What was it that first drew you to Albuquerque from Chicago?

I was doing a lot of drugs in Illinois. We thought moving to New Mexico would fix it. The desert stripped everything down. No distractions, no hiding. The sun here burns slow, you don’t know if it’s helping or burning you alive. I had to learn that the hard way.

“My work isn’t here to entertain, seizing what’s in front of me before it vanishes is the mission.”

You photograph a lot of gang members, former addicts, the insides of trap houses. How do you go about gaining the trust of the people you photograph?

The spaces are threatening. I never forget that. Yet truth finds a way inside—it strips everything down. No armor, no pretense. That willingness to step into their reality is what earns me the chance to photograph it.

A decade ago I would just knock on random doors and stop people walking on streets to take their portraits. Back then I carried this blind optimism, like safety was guaranteed. The city shifted, crime rose. Parts of Albuquerque became more violent and having been robbed at gunpoint, I had to take precautions. In my earlier work, I encountered killers out on bond on the sidewalk, and I wanted to capture their prison tattoos. A guy had a huge gang emblem across his forehead, he said he was going rob me—he said it so calmly. My hand was shaking as I was holding the camera. He laughed and just rode off.

How would you describe your relationship to the people you photograph? Are you strictly an observer or do you feel more connected?

I am more of an observer now. Shooting documentary-style, it’s wise to shut up and remain quiet. Moments can fade within seconds and never return. I thought silence had to be fought off, so I filled it with conversation. Silence isn’t empty, it’s the canvas. People show themselves when they forget you’re there.

One man you photographed told you that “learning about guns at a young age is like our version of Boy Scouts in New Mexico.” How would you describe gun culture there?

Kids carry guns in New Mexico. Teens feel vulnerable to physical harm and a gun simply provides a sense of security. That’s what they all tell me. Yet over the summer, in downtown Albuquerque, I saw a young girl gripping an assault rifle while driving a pick-up truck. Her head, so tiny in this huge vehicle with pink aftermarket interior lights flashing to a pattern of stereo music—clutching the rifle with her free hand as it stood up on the floorboard.

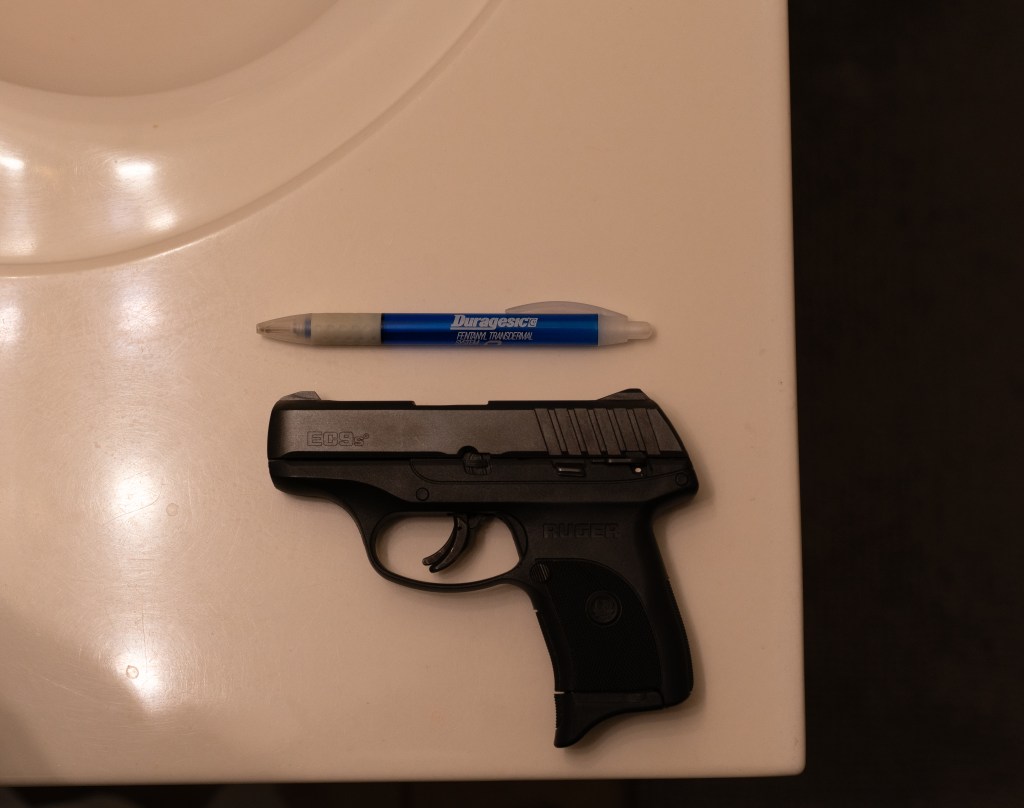

What’s the story behind the pen and the gun?

I was photographing inside a trap house, more like trap trailer, when I found that pen. One of the women living there worked at a CVS years back, pocketing promo items from sales reps. I was locked in the bathroom while the others used. Nobody wanted a camera around in those moments. The pen and the gun together felt like artifacts, addiction and survival, commerce and violence, the realities of New Mexico condensed into objects on a sink.

“I was locked in the bathroom while the others used. Nobody wanted a camera around in those moments”

In a previous interview, you mentioned that around the time you started pursuing photography and self-promoting on Instagram, locals and old friends would hit you up asking you to take their portraits. What do you think is the impulse behind that?

At that time, I was kicking heroin and oxy. I was researching documentary stills from the FSA years up to the early 1990s. I read photographers simply shot what was in proximity to their homes. One night, desperate to shake the sickness, I said fuck it, grabbed my camera and left. It became a form of detox—every click of the shutter was a way to outpace withdrawal.

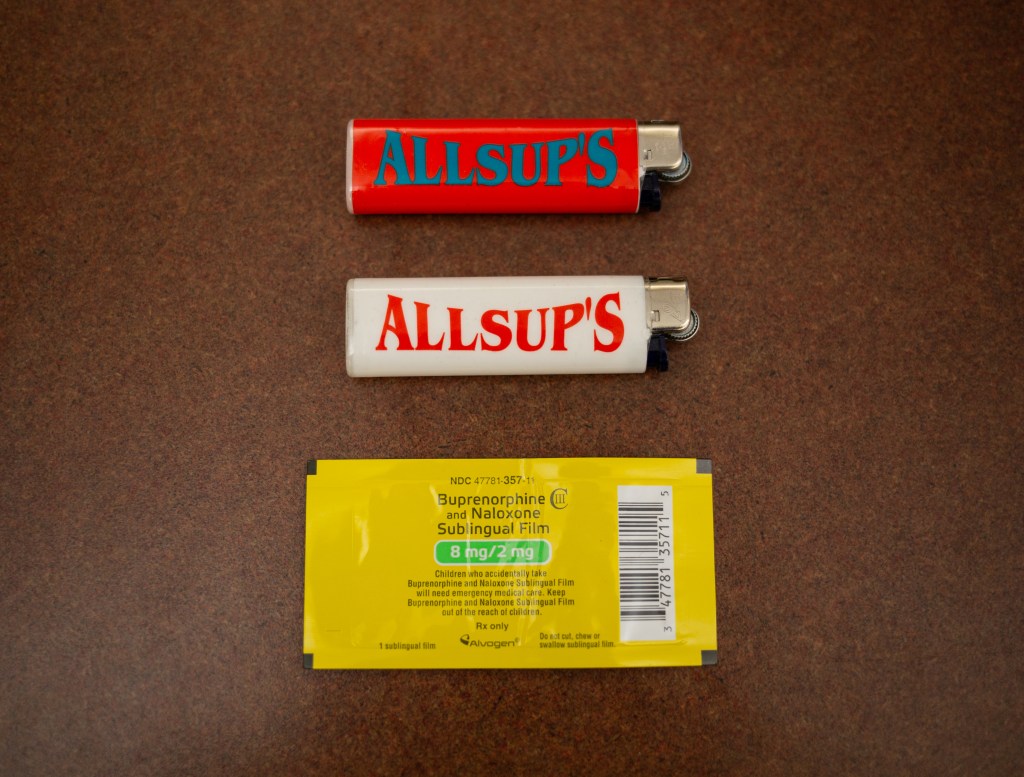

Weird prison tattoos, handguns on tables, Suboxone strips, old trailer homes. I wanted to keep a textbook for myself with notes in the margins, almost like a fucked up encyclopedia or something. Those first nights of withdrawal are strange—the body switches between exhaustion and manic surges of drive. I tried to burn time until the sickness passed. In those early years it was easy because my first subjects knew me. Then I started to branch out to real street photography, walking block to block.

There’s a real tenderness to your work. Obvious hardship, but warmth and resilience too. How would you describe your style?

I can explain the process of my technique sort of like this: I investigate to determine what frame/moment I’ll never see again. I try to catch that one piece of light in between a transition of thought, it’s the most authentic.

My style pushes to maintain congruency between intention, free will, and risk, a slippery trio artists usually lose control of. Like a blue marlin, you think it’s hooked until the line snaps.

The warmth is likely pulled from my first memories of opiate usage. Before I got sober, chasing that perfectly manufactured hot tub temperature along my spine was everything. Painkillers uncovered a hidden thermostat wired to my body, a private control over joy and pain. Maybe art is a way for me to feel it again.

You’ve lived in New Mexico for a long time now. How have you seen it change?

Guns. More guns. The shift isn’t abstract, it’s audible. Automatic rifle fire rattles through the air more often, the sound embedded in daily life. And it’s not just Albuquerque; it’s America’s soundtrack. The rhythm of mass shootings has become background noise, a culture that measures time in gun deaths.

There have been several high-profile ICE raids and counter-protests in Albuquerque over the last few months. I’m wondering what the impact of the current climate has been on the individuals you work with, and how communities are responding to it?

ICE is here now in New Mexico. The National Guard rolled in this past summer. Some of the people I photograph barely blinked. Business as usual. For the government, the optics are clean and convenient, but on the ground the suffering doesn’t change. Addiction defeats any deployment. The rot runs through poverty, erosion of family bonds—all controlled by chemical dependency. Troops and federal reinforcements are useless against substance abuse.

You mentioned in a previous interview that often the people you photograph identify as New Mexican before anything else. I’m curious to hear more about why you think that is, and whether that connection has changed—or even strengthened—in light of recent events?

There’s an unwavering connection to statehood here. Families can trace their ancestry back to this exact land as far as the 16th century, further still for Native American communities who’ve been rooted here since long before. New Mexico is stitched with that history, and despite its fractures, most people will tell you the same thing, this place is, and always will be, home.

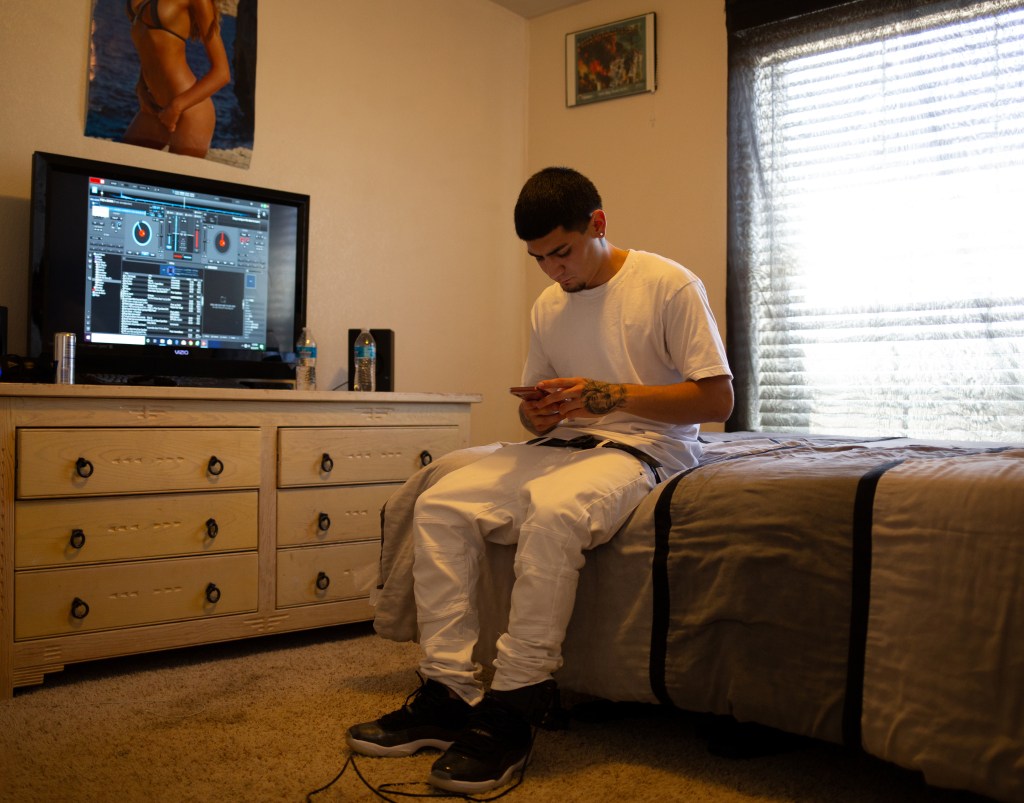

Zach Gutierrez, who appears in one of the photos you sent over, sadly passed away this summer. Would you be happy to talk about your relationship to him?

In 2019 I read a local story about a 17-year-old charged with first-degree murder. A man walking his dog in Santa Fe was killed, and this kid was out on bail. I wanted to know what life looks like for someone that young, facing the possibility of living inside of a concrete box forever. He always swore he was innocent. I expected a teenager waiting for a murder trial to be in a perpetual state of anxiety. Zachary wasn’t. He played video games, made music, moved through his days like normal. In 2021 he was cleared of that charge. He died in June of this year.

Zachary was a kid on a heavy supply of buprenorphine—like he would take three normal-dose 8 mg/2mg strips a day. He told me about his life as a child-runaway, accepting realities at such a young age. It was certainly unsettling to watch him, this youngster, charge his court ordered ankle monitor like an iPhone.

The nature of your work, and the pockets of society you focus on, does put you in fairly close proximity to loss of life. How do you deal with that on a personal level?

Several of my subjects are dead now. Street life. Wrapping my head around the fact I’ll never see them again is unbelievable. I photographed a man named Felipe in 2017 and six years later he was shot to death. There’s a coldness to it that I try to dissociate from. Part grief, part regret, part impossible wish that I could move time, step back into that moment, and stop it from happening. That’s the hardest part of this work, you carry their faces, but not their futures.

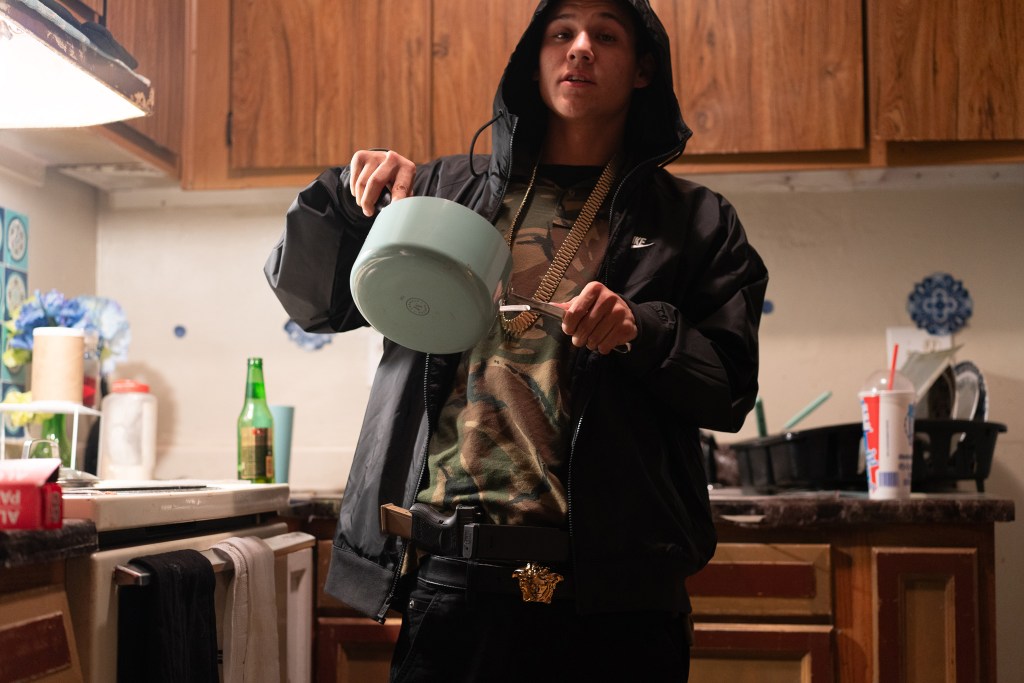

The photo of Zombie and the photo of the teenager making macaroni are two of my favorites. They feel oddly juxtaposed to me—the kid cooking dinner with a pistol in his waistband, and an established drug dealer doing comparatively chill-looking admin in a Motel 6. They kinda reflect aspirations and reality, if you know what I mean.

Yes, it’s a rhythm of existence. Zombie is a typical shards dealer. I once watched him smoke crystal out of a glass bubble right in front of an Albuquerque police officer with no consequences. He carried himself with this confidence—he knew exactly what he could get away with. I was staring at the ground thinking, holy shit, he’s about to get arrested in seconds. Nothing happened. That’s when I realized how far I was from the reality of the entrenched life of a street addict.

The kid cooking with pistols in his waistband, that’s innocence colliding with survival, childhood and adulthood caught in the same frame. And those extended magazines sticking out. To me they looked absurd, like Lego blocks or power tools at first glance. That strangeness is what makes the image potent, so surreal it becomes ordinary.

You can find more of Frank’s work on Instagram.

The post Inside the Trap Houses of Albuquerque’s ‘War Zone’ appeared first on VICE.