When I was a kid, living in Lawrenceville, Virginia, I heard tales about how the James River was haunted: perhaps by the spirits of Indigenous people who were forced off this land, or maybe by those who gave their lives to revolution, or maybe by enslaved men, women, and children who drowned while trying to escape their plantations. The ghost stories seemed to suit a river that’s connected to America’s soul. Supernatural or not, the James carries a certain significance, traveling through the capital of the Confederacy and then to the first colonial capitals, following the contours of the nation’s story. It’s a wellspring for historians and conjurers alike.

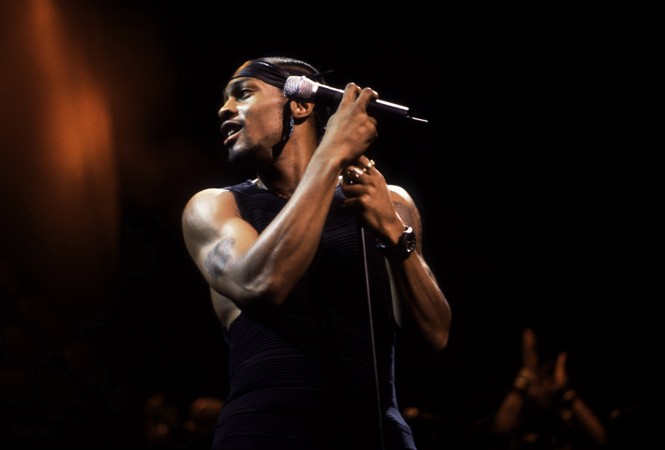

One of the greatest of those conjurers is now gone. D’Angelo, the musician born Michael Eugene Archer, died on Tuesday after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was an enigma who defined a musical era, a recluse who battled his own demons, a runner who—in the tradition of his forefathers—sought a modicum of liberation for himself and his people. At just 51 years old, D’Angelo joined the ranks of many Black luminaries who shined brightly but not long.

For much of D’Angelo’s career, critics seemed to most appreciate his brilliance by way of comparison. After the release of his 1995 debut album, Brown Sugar, he was anointed as the vanguard of the nebulously defined “neo-soul” sound—a modern-day Smokey Robinson with straight-back braids. With his follow-up masterwork, Voodoo, D’Angelo was deemed an heir to Prince, another funk virtuoso whose sex-charged music upended R&B orthodoxy. What that type of praise seemed to value most wasn’t necessarily what D’Angelo was saying or trying to do, but the bygone mastery he evoked. For an artist who had alchemized his collection of Prince, A Tribe Called Quest, Roberta Flack, and Marvin Gaye records into a beautiful sound of his own, this was never a slight. But it did always feel like a flattening of a kind.

This flattening was evident in other ways too. Any number of obituaries and tributes have mentioned the music video for his hit single “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” in which a seemingly nude D’Angelo sang directly to the camera and, at times, toward his unseen pelvis. The video was considered near-pornographic by many viewers, and it went as close to viral as was possible in the pre-social-media world, driving the commercial success of the single and the album. At concerts, screaming fans began to demand that D’Angelo strip, some even throwing money on stage. As the legend goes, the wave of objectification was so massive that it sent him into seclusion for more than a decade.

In interviews over the years, D’Angelo tried to downplay that version of the story, but what’s clear at least is that he felt discomfort over the idea of his image becoming bigger and more important than his music. He was born in Richmond, Virginia, and raised in another town on the James River, growing up in a fire-and-brimstone Pentecostal church where he learned piano and other instruments at an early age. As the son of pastors, he’d absorbed the dogma that man was inherently fallen, and utterly irredeemable without the grace of God. One way to claim that grace was through displays of spirit, which the right music could coax out of even the most staid congregants. While preachers preached, D’Angelo learned ministry from the choir stand, leading the flock to epiphany one measure at a time. He never left behind that intentionality of purpose, even when music became business.

But the church also taught that the power of music could be corrupting. There have long been debates in churches about whether just listening to worldly music was sinful, let alone playing it. Music could bring people to sin just as easily as it could bring them to salvation, and if its holy iteration brought the faithful to the climax of speaking in tongues, then its unholy version promised a climax of the flesh. D’Angelo found power in this duality, smashing the barriers between the spiritual and the secular, as had so many Black music pioneers before him. He built songs about sex with chords from a Hammond organ that sounded like it was still plugged in at a choir loft. He described the capitalist pursuit of wealth as a devil’s bargain, and spoke of curses placed on him by vengeful root-workers. In borrowing from a patchwork of references, and steeping them in a brew both sacred and profane, D’Angelo was doing more than homage. He was conjuring.

As well regarded as Voodoo is, it’s rarely discussed as a statement about Blackness and the world. Raphael Saadiq’s woozy bass line and fiery guitar licks announce “Untitled” as a clear Prince tribute, and the album’s sonic peak. But immediately after, “Africa” directly samples Prince, and also channels the Purple One’s underrated penchant for commentary. In that song, D’Angelo uses the occasion of his son’s birth to consider his ancestry. The drums are gentle and stirring; the arrangement evokes a pulsing lullaby. Written with Angie Stone, D’Angelo’s former partner (who also died earlier this year) and the mother of one of his children, the song ponders what it means to be part of a larger story of grief, hope, and struggle. “Africa is my descent / and here I am far from home,” he sings. “I dwell within a land that’s meant for many men not my tone.” The lyrics position the song, and perhaps the album, as something of an inheritance, a legacy that will live beyond its creators’ lives.

D’Angelo clearly viewed his own creations differently than many onlookers. The attempt by critics to define his work as “neo-soul”—and by extension, to sometimes cast his collaborators and fellow travelers as homage acts—was always instructive. “I never claimed I do neo-soul, you know,” D’Angelo told an interviewer in 2014. Instead, he preferred to say that he made “Black music.” Not a recycling, but a continuation—a long communion with the dead, the living, and the yet-to-be born.

This was all perhaps most evident on D’Angelo’s third studio album, which turned out to be his swan song. Black Messiah, released after a long hiatus—which included documented struggles with addiction and mental health, and related legal troubles—was messier and less interested in abiding by genre than his previous efforts. There were stabs at horny lounge jazz, a melodramatic Latin guitar ballad, even a folksy blues number. Yet the songs, situated in the melange of Black music, cohered through D’Angelo’s resolve. The album’s musical expansiveness was matched by the breadth of its social commentary. On “Till It’s Done (Tutu)” he worries about climate change, and presents a conundrum that’s newly relevant in today’s flood- and fire-stricken America: “The question ain’t ‘Do we have resources to rebuild?’ It’s ‘Do we have the will?’”

In “1000 Deaths,” D’Angelo’s voice is nearly drowned by the chaotic mix, a wall of guitar and bass that evokes apocalyptic fire and uprisings in Black ghettos. The lyrics are purposefully difficult to parse, but they are not without meaning. In what functions as the song’s chorus, D’Angelo sings, “Because a coward dies a thousand times / but a soldier only dies just once.” In chanting “Yahweh, Yeshua”—the Hebrew names for God and Jesus Christ—he presents himself as a soldier for the godhead. But his Christ is Black. The album’s title calls back to this image of a revolutionary Black Jesus, a Messiah for America’s modern racial strife. It also references the secret COINTELPRO program, run by the notorious FBI director James Edgar Hoover and designed to infiltrate and sabotage civil-rights organizations across the country. In the late 1960s, Hoover’s office sent a memo warning of the potential rise of an earthly Black “messiah,” a leader who might unite Black communities in opposition to American oppression.

D’Angelo and his collaborators had intended for Black Messiah to be released in 2015, and many of the songs had existed in some form for years. But in 2014, rage in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, over the killing of Michael Brown by police helped stoke a movement that shaped the next decade of American life. The band and studio worked feverishly to get the record out in time to meet the moment, and it arrived in the winter of 2014. It was not D’Angelo returning to the world, but the world finally catching up to him.

If the ongoing American crises of culture, technology, and government share a common thread, it’s the steady advance of—for lack of a better term—fake shit. Our phones are turning into pocket-size casinos, offering windowless retreats from the real. Bots argue with bots on social media, and the slop churned out by AI is then regurgitated by different AI. The stock market seems ever more divorced from economic fundamentals, and the American military is being ordered around by a man who watches news clips of his own debates and rallies and grows convinced by his own made-up arguments. At the bottom of our splintering reality, there is still real art—real endeavors, inspirations, and feelings. But more and more, they’re covered in mounds of fake shit.

To me, one antidote for those malaises is the embrace of craft for craft’s sake. D’Angelo could become a patron saint for this ethos. He was infamously particular, and his relative lack of studio output compared with his peers wasn’t a result of disinterest in making music, but rather the opposite. He made so much music, both within the studio and without, but he only deemed a part of that corpus worth sharing with the world.

The traditional containers of albums and singles never seemed to be enough to hold his intentions. D’Angelo approached making music the way Black grandmothers approach making biscuits on Sunday before church; the way dorm hair braiders approach stitched cornrows; the way bandleaders in New Orleans approach second lines; the way fire-and-brimstone preachers approach Easter service; the way quilters approach quilting. Drawing on knowledge passed down from the ages, they work hard to perfect their craft, not just because of the promise of a transaction or consumption, but because the doing is the thing. So it is with making music, and the impossible task of assigning form to the ineffable. Sometimes the process is slow, painful, inefficient, or imperfect. But we don’t make art because it’s quick and easy.

One common Black folk analog to the craft of music-making is that of witchcraft. Robert Johnson sold his soul for the blues; Jimi Hendrix was himself a voodoo chile. In this tradition, there is something transcendent or ethereal about the power of music, and about those trained to wield it, who raise the dead and stir the living. But as in witchcraft, the process can be arduous and uncertain. And it always costs something.

Even the most fantastic stories of roots and voodoo have always captivated me, not necessarily because I want to believe, but because I see in them attempts to explain the real ways that human endeavor and experience extend beyond the physics of this world. In those stories, rivers tend to have special significance: as ritual sites, as fonts of mystic energy, as places where you might depart one world and enter another. For those who seek the other side, whether it be with Charon in the Styx or the ferryman on the James, some sort of craft is necessary.

The post The Death of a Black Messiah appeared first on The Atlantic.