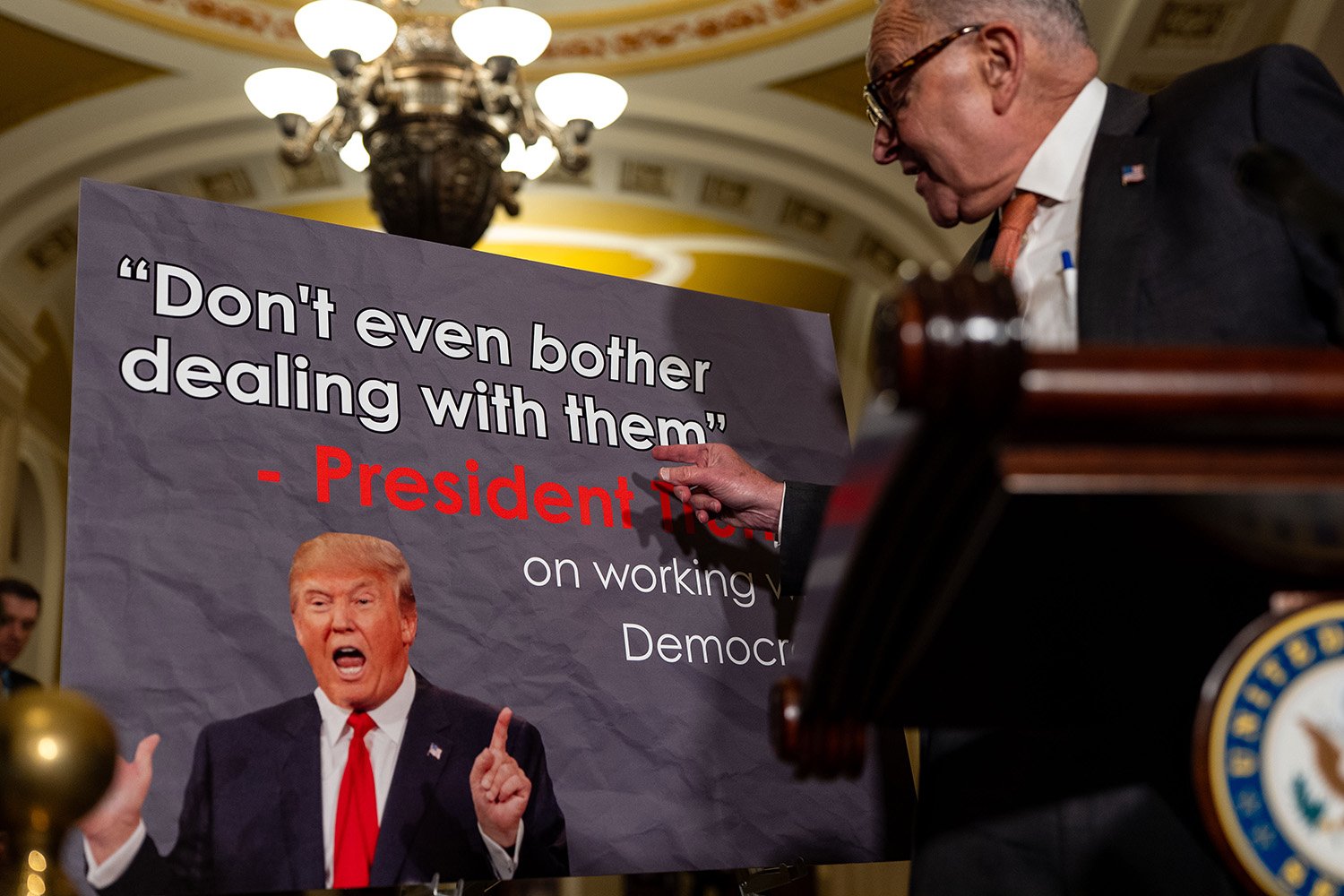

As the two-week standoff over the U.S. government shutdown dragged on—imperiling hundreds of federal programs that the Democratic Party has created over the past century—the nation’s top Democrat, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, suggested at one point that he’s fairly satisfied with his party’s progress.

“Every day gets better for us,” chortled Schumer, apparently full of vim that he wasn’t swiftly surrendering to President Donald Trump as he did to avoid a shutdown in March.

But few in the country agreed—and Democrats continue to earn record-low ratings among voters (who still trust Republicans more on economic issues, even though the Democratic Party is polling slightly better on the shutdown). And therein lies the latter political party’s long, woeful tale of impotence against Trump, the most powerful demagogue that the United States has ever seen.

Even as Schumer was preening on Capitol Hill, Russell Vought, Trump’s zealous Office of Management and Budget director, was halting billions of dollars in funds for Democratic-led states and using the shutdown to pursue his long-term plan of inflicting “trauma”—in the form of mass layoffs—on what Vought has condemned as a pro-Democratic federal workforce.

Trump, meanwhile, directed his Justice Department to begin to indict leading Democrats, starting with New York Attorney General Letitia James, and he ordered National Guard troops into Chicago while threatening Illinois’s top Democratic officials with jail time. That prompted one of those officials, Gov. J.B. Pritzker, to rail against “do-nothing Democrats” back in Washington, saying, “This is exactly the moment for people to stand up. And do I see enough people doing it? No, I don’t.”

Nor does anyone else. The party’s most recent standard-bearer, former Vice President Kamala Harris, seems mainly focused on relitigating the past as she continues a tour for her new book 107 Days—Harris’s somewhat self-pitying account of her failed presidential run—in which she writes that she predicted Trump’s scorched-earth agenda and says, “I warned of it. What I did not predict: the [Democratic] capitulation.”

Rather stunningly, Harris then advises her fellow Democrats: “We need to come up with our own blueprint that sets out our alternative vision for our country.” Huh? Isn’t that what Harris was supposed to be doing when she ran for president?

Bottom line, Democrats have a lot of anger and angst these days but still no real agenda. Since the debacle of 2024, a great deal has been written—and is still being written—about how the party lost the working class to Trump by moving too far left on cultural, so-called woke issues. And how even now, the Democrats are so beholden to far-left progressives that the party leadership can’t find a way back to the center.

This criticism explains a lot. But there is a larger historical trend that also explains why the party is still wandering in the political wilderness. Basically, since the New Deal and Great Society era—in other words, more than a half century ago—the Democrats have mostly failed to put forward their own agenda and have been mainly counterpunching. That is, adapting to and co-opting the Republicans’ agenda—or, more accurately, a “political order” imposed by the other side (to use Cambridge University scholar Gary Gerstle’s term)—whether on economics or foreign policy.

In his forthcoming book After the Fall: From the End of History to the Crisis of Democracy, How Politicians Broke Our World, Yale University political scientist Ian Shapiro argues that these failures of the liberal/progressive side of the spectrum to set the agenda are part of a broad ideological surrender that spans the Atlantic.

The failures of the Democrats in the United States were also the failures of their left-of-center counterparts in Britain and Europe. Among them were former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s New Labor; the French Socialist Party leader and former President François Mitterrand—whose tournant de la rigueur or “turn to austerity” in the 1980s presaged the route that U.S. President Bill Clinton later took—and, in Germany, the Social Democrats and Green party.

For all these players, the end of the Cold War and its implicit message that government-directed economies never work—and free markets always do—left them bereft of a message, and they still can’t keep up, according to Shapiro.

“Unlike during the New Deal and Great Society, when there was an alternative ideology competing for the hearts and minds of workers in the West, these parties had no place to go,” Shapiro said in an interview. “All of this goes into overdrive at the end of communism. And it’s not until after the [2008] financial crisis that a lot of these elites realize [that] the legitimacy of what they’d been shoving down the throats of voters was seriously in question. Instead of new solutions, they responded with more of the same and made it worse because they bailed out the banks.”

“Now, except in Spain, all these [liberal] parties are running scared of the far right,” Shapiro added. Hence, Trump’s success in the United States has been mirrored, to a degree, by the popularity of the Alternative for Germany party and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party in France.

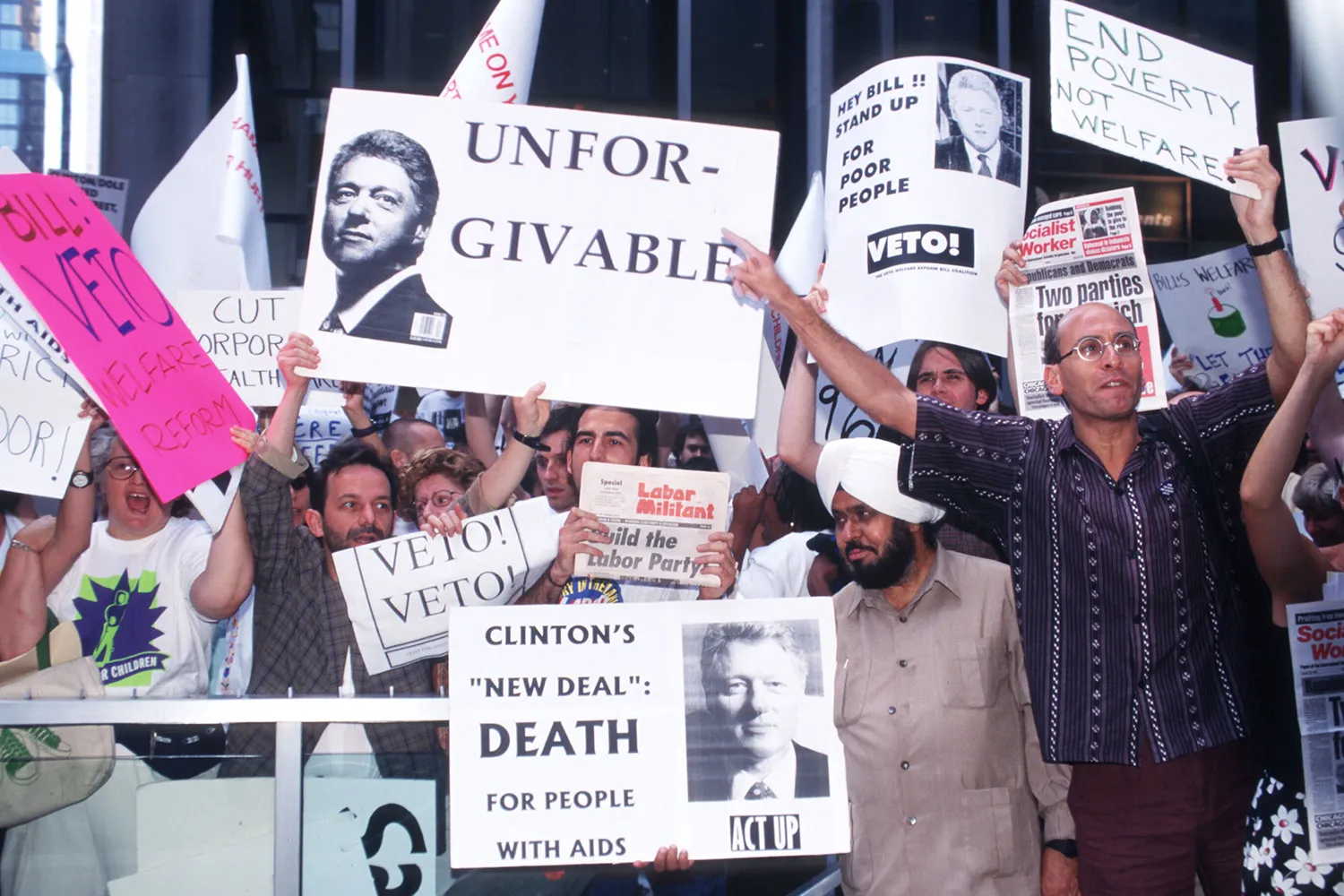

In the United States, two previous Democratic presidents, Clinton and Barack Obama, effectively admitted to such an agenda-surrender at various points during their presidencies. In 1996, Clinton delivered his famously Reaganesque declaration that “the era of big government is over.” He became an eager deficit hawk—lamenting at one point that he had gone from being a liberal Democrat to an “Eisenhower Republican”—and adopted a Republican Party-inspired “workfare” program over welfare while letting Wall Street run rampant.

Obama poked fun at Clinton for this approach as he ran against Hillary Clinton in 2008, saying that Bill Clinton hadn’t “changed the trajectory” of the country the way that former President Ronald Reagan had. But Obama later admitted to a group of economists that he himself found it hard “to change the narrative after 30 years” of Reaganite thinking.

And in the end, Obama did little better than President Clinton. Under pressure from the right, Obama—like Clinton—became a determined deficit cutter and did little to correct deepening economic inequalities that actually became worse during his presidency (with the exception of health care, but even Obamacare represented a big concession to the insurance industry). A big example was complying with his neoliberal-leaning financial advisors, Tim Geithner and Larry Summers, when they pushed for a smaller-than-needed stimulus after the 2008 financial crisis and argued that the “moral hazard” of bailing out millions of underwater homeowners was too risky while dismissing the moral hazard of bailing out big banks.

And when neoliberalism—or more plainly, Reaganism—came crashing down along with Wall Street after the crisis of 2008, it was yet another Republican, Trump, who took the country in a starkly new direction, brazenly embracing trade war, protectionism, and “America First” neo-isolationism.

Here too, the Democrats are still playing catch-up. Compared to Trump and his MAGA movement’s “post-neoliberalism,” the left’s version remains “undercooked,” as Daniel Schlozman of Johns Hopkins University and Sam Rosenfeld of Colgate University described it in a recent paper. To put it more succinctly, Trump succeeded in remaking his party’s agenda while his closest populist counterpart on the left, Sen. Bernie Sanders, did not.

Ironically, the one Democratic leader who did genuinely try to create a major post-neoliberal agenda for the party—and succeeded in part, at least more than the others—was former President Joe Biden.

In the face of the global COVID-19 lockdown and the threat from Trump, Biden sought to forge a New Deal-sized presidency, telling his chief ideas guru, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, to embark on a program of “updating Roosevelt for modern times,” according to Chris Hughes’s new book, Marketcrafters. Biden oversaw legislation intended to transform how Americans saw the role of government, including massive stimulus spending and major industrial policy and climate initiatives in the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

But because Biden badly fumbled the politics of the moment—insisting that he deserved a second term despite deep voter concerns about his age and playing down persistent inflation—he is now persona non grata in his own party. Consequently, no one is eager to embrace Biden’s agenda.

“The Biden Administration deserves credit for pioneering modern industrial policy while also advancing the legislation needed to get it done,” a former senior Biden and Harris advisor, Rebecca Lissner, told me in an email. “The difficulty is that the agenda was incomplete after one term.”

Or as Yale’s Shapiro put it: “Biden really is the first Democrat to try and rebuild a Great Society-type coalition, but he was kind of a day late and a dollar short.”

Yet even during the Biden era, the party was in part reacting to and co-opting parts of the Trumpist agenda—especially neo-protectionism—rather than forging its own unique path.

“To the surprise of many, Joe Biden, as thorough a creature of the Washington establishment as has ever held the presidency, accepted many of Trump’s premises,” write Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in their new best-selling book Abundance.

The Klein-Thompson book is itself a fresh effort at Democratic agenda-setting—an attempt to promote what the authors call “supply-side progressivism” or a new kind of public-private-sector partnership. And Abundance is undoubtedly helping to shape an important Democratic debate over how to bridge the divide between the failures of the neoliberal center and the extremes of the progressive left, as exemplified by Sanders and Co. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom—a possible contender for the 2028 Democratic presidential nomination—posted recently that “we’re urgently embracing an abundance agenda.”

Even so, a number of critics say the Abundance agenda falls well short of a true ideological breakthrough—as opposed to resembling a kind of rejiggered Clintonian centrism with a measure of former President Jimmy Carter’s deregulatory mindset thrown in.

As Klein and others have previously noted, Biden himself promoted a version of the abundance agenda while in office—what his Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called “modern supply-side economics”—seeking, for example, to increase the housing supply by eliminating exclusionary zoning laws. (Though Biden’s programs relied mainly on public investment, not deregulation.)

On foreign policy, too, Democrats have also been largely adapting to Republican agenda-setting, at least since former President George W. Bush invaded Iraq, some critics argue. Recall that Obama first rose to prominence—and defeated Hillary Clinton, an Iraq war supporter, in 2008—by calling Iraq a “dumb war.” But Obama later adopted a similar tack in the so-called war on terror, or what came to be called the “forever war”—which, despite lamenting, he effectively prolonged by authorizing countless covert drone strikes, intervening disastrously in Libya and surging troops in Afghanistan.

“Here, too, the Democrats had no alternative; they were just complaining about what Bush was doing,” Shapiro said.

Later, after the financial crisis hit, Obama’s treasury secretary—Geithner—followed a bank-friendly path similar to that of his Republican predecessor, Hank Paulson. Biden also pursued Trump’s plan for a swift withdrawal from Afghanistan, much to his later grief.

This ideological vacuum at the heart of the Democratic Party may also help explain why Hillary Clinton lost in 2016 and Harris lost in 2024: Voters perceived, fairly accurately, that these candidates had no real coherent agenda of their own other than “don’t vote Trump.” Both candidates spent most of their campaigns arguing that Trump was unfit for the presidency and very little time delivering a compelling message about why they would be better.

Judging from her post-2016 memoir, What Happened, and various other accounts, Hillary Clinton never fully grasped that the seeds of working-class anger that sank her campaign were planted during her husband’s presidency, with its neo-Reaganite embrace of Wall Street deregulation, deficit-cutting, and untrammeled globalization—policies that left little room for job retraining for U.S. workers displaced by the “China Shock.” Cue the sudden rise of Sanders—and Trump.

As for Harris, many critics would agree that she also failed to offer an overarching vision that made much sense. Instead, Harris constantly “vacillated between competing visions for how to address the economic problems that voters repeatedly ranked as their top issue,” Nicholas Nehamas and Andrew Duehren wrote in the New York Times in a postmortem on what the headline called her “Wall Street-approved economic pitch.”

Harris’s campaign was also paralyzed by a bitter internal conflict over messaging—in particular, whether it should focus on the danger to democracy posed by Trump or bread-and-butter issues such as the economy.

So the Democratic Party’s identity crisis has a long history and very deep roots—and that has made it all the easier for Trump to create a new political order in the United States and, arguably, the world.

“What the party needs is a ‘Project 2029,’ but no one is really doing it,” Shapiro said.

Colgate’s Rosenfeld argued, however, that what’s needed is more than just getting the policies right. “Harris saying the Democrats need a blueprint—yes, in part, that’s a self-indictment,” he said in an interview. “But to say a blueprint or policy vision is what you start with is probably wrong.” What’s needed first, he said, is some kind of intraparty agreement on “big broad values and principles that speak to the moment, allowing for a lot more kinds of people and organizations locally and subnationally.”

Instead of that, Rosenfeld said, today’s “Democratic hollowness” is “manifested in a big sprawling blob of nonprofits, issue advocacy groups, think tanks, and policy intellectuals, and there’s very little in the way of real organization. Nobody is in charge. There’s no real mechanism to set priorities that you had in the New Deal and Great Society eras.”

This is why Trump is more likely than not to come out of the shutdown looking like he won, even if he backs down on the health care standoff in which Democrats are refusing to vote for a new spending bill unless Obamacare subsidies are extended. As a recent Wall Street Journal article reports, Trump himself seems to be surprised that he has faced “little resistance to his ambitious agenda” and “has even remarked to aides that he is shocked how easy it has all proven to be.”

But perhaps it’s less surprising when one considers that Trump is pushing up against the mere “hollowness” of his opponents, as Rosenfeld and Schlozman describe it. Democrats went from being true retail politicians with deep roots in their communities and turned into “proponents of data-driven politics” built on polling, thus failing to create a “common cause” or “public philosophy” for the party, they write.

“As a result, the Democrats remain a party that cannot bring the horses together,” Rosenfeld and Schlozman argue.

Party agendas and political orders, of course, go in cycles—and usually are created to address the failures of their predecessors. A century ago, former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was a response to 12 years of failure by Republican presidents to rein in the laissez-faire policies that ultimately led to the Great Depression. And the dominance of Roosevelt’s Democratic agenda in that era was accompanied by political ineptitude on the part of Republicans as much as today’s Republican dominance is built on Democratic directionlessness.

At the bottom of these reversals of fortune are usually major policy errors. If Roosevelt’s New Deal was a response to the excesses of the Republican Party’s laissez-faire policies—too little government—then Reaganism was a response to the failures of too much government in the wake of the New Deal. This mainly emerged as terrible Vietnam War-era inflation compounded of exorbitant spending on the war and Great Society-type government programs and the stagflation that followed.

Trumpism, in turn, is partly a response to the failures of post-Cold War Reaganism to bring equitable prosperity shared across economic classes, as well as the backlash from titanic errors of overreach abroad such as the Iraq War (which also stemmed, to a degree, from the hubris of neo-Reaganite hawks such as Paul Wolfowitz—one of the chief promoters of the war—who, like Reagan were convinced that “evil” regimes should be toppled).

It is likely that the future of the Democratic Party, too, will depend on the long-term success or failure of Trumpism. One problem today, of course, is the sheer relentlessness and rapidity of Trump’s agenda. Lissner, for one, suggested that “the narrative of Dems adrift” may have less to do with a lack of “policy ideas” right now than “being forced into a reactive mode given the daily chaos of this White House.”

Perhaps. But it’s also true that the Democrats appear to be so lost that many are still focused on the words that they’re using rather than the substance of what they’re actually saying. Over the summer, the center-left think tank Third Way put out a list of nearly 45 words and phrases that it warned Democratic elites against using with voters, including politically correct terms such as “cisgender,” “birthing person,” and “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, people of color). Such terms, Third Way said, reflected “the eggshell dance of political correctness” and put “a wall between us and everyday people of all races, religions, and ethnicities.”

No one on the Democratic side has quite figured out yet how to get over that wall.

The post Why the Democrats Are So Lost appeared first on Foreign Policy.