A picture book is a deceptively complex object: Ideally, it should be mind-expanding, psychologically astute, vividly illustrated, and—the most elusive criterion—fun. It must entertain the child without boring the grown-up to tears. And it should teach children to match sounds to meaning, pictures to objects, cause to effect, without feeling like homework. Finding picture books is easy; the market is glutted with them. The hard part is picking out just the right ones. What follows is an effort to bring clarity to the earliest years of literacy, and to help foster a child’s lifelong relationship with books. We hope this selection will assist harried caregivers in sorting the wheat from the chaff, while also giving these formative works the respect and scrutiny they deserve.

Because children’s books vary so much according to age, we decided to limit our scope to titles that lead up to the transition from listening to an adult’s narration to reading independently: illustrated stories without long chapters, meant to be shared. We then asked authors, librarians, and other experts for suggestions and debated works among ourselves, stress-testing both classics and newer books to come up with our final list—of titles you know and those you should.

Over the course of our project, some trends emerged: 1955—peak Baby Boom—was an auspicious year for the genre (when Eloise, Miffy, and the crayon-wielding Harold were created). The 1960s and ’70s brought bold colors and loopier styles to the fore. The 21st century delivered a wider array of stories—migrant journeys, portraits of grief, African and East Asian folktales. No single trait unifies the works below, but each represents a feat of artistry, voice, or complexity that we found exceptional. They are the kinds of books that will be cherished well into the future, worn from use and perhaps replaced more than once. Because of this, they felt essential.

Explore the best children’s books

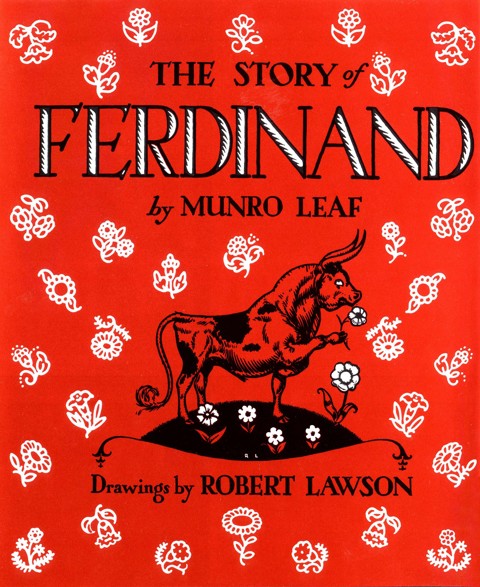

The Story of Ferdinand

by Munro Leaf, illustrated by Robert Lawson

1936

The plot of Ferdinand is deceptively simple: A bull who wants only to sit quietly under a tree is mistaken for a fierce beast and sent to a bullfight. There, he refuses combat, instead smelling the flowers in the ring. The tale may seem like a classic misfit story about a boy who doesn’t fit in with his head-butting peers. But unlike many other literary outcasts, Ferdinand is never ashamed to be different; he remains peaceful in a violent world. That was a divisive message when the book was published, with the Spanish Civil War under way and World War II approaching. Critics called Ferdinand communist, fascist, pacifist (as well as anti-pacifist), and emasculating; Adolf Hitler banned it for being “degenerate democratic propaganda.” Today, as many warn of a crisis in masculinity, Ferdinand’s unwavering gentleness feels refreshing. Leaf writes that the bull resisted fighting “no matter what they did”—a level of fortitude that may inspire children, even if some adults are more cynical.

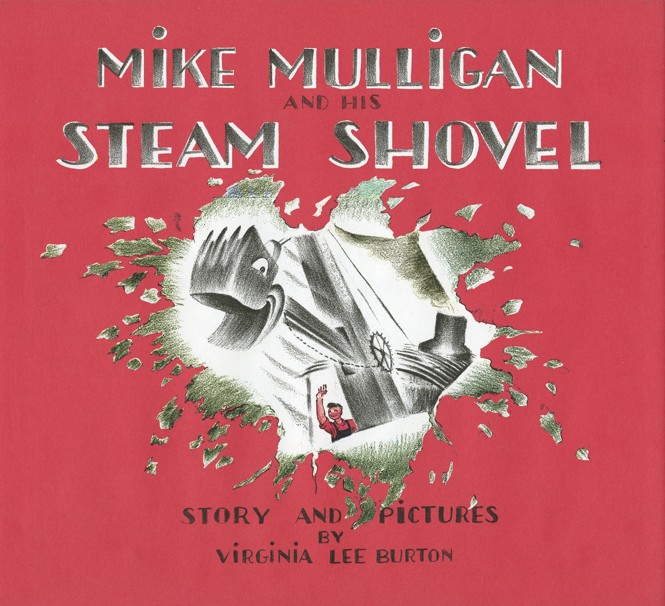

Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel

written and illustrated by Virginia Lee Burton

1939

Mary Anne is a good shovel, and Mike Mulligan is her good friend. Together, the two of them (and some others) have made canals, freeways, and tall skyscrapers in big cities possible. But steam shovels are quickly being replaced by more powerful machines, and Mary Anne and Mike have nowhere left to dig. Nowhere, that is, but Popperville, where a town hall needs a cellar, and the two need to prove that they’re still useful in a world that’s changing very fast. No one under 10 knows what a steam shovel is, but they don’t need to—Mike Mulligan is about taking pride, taking care, and working hard until the job is done.

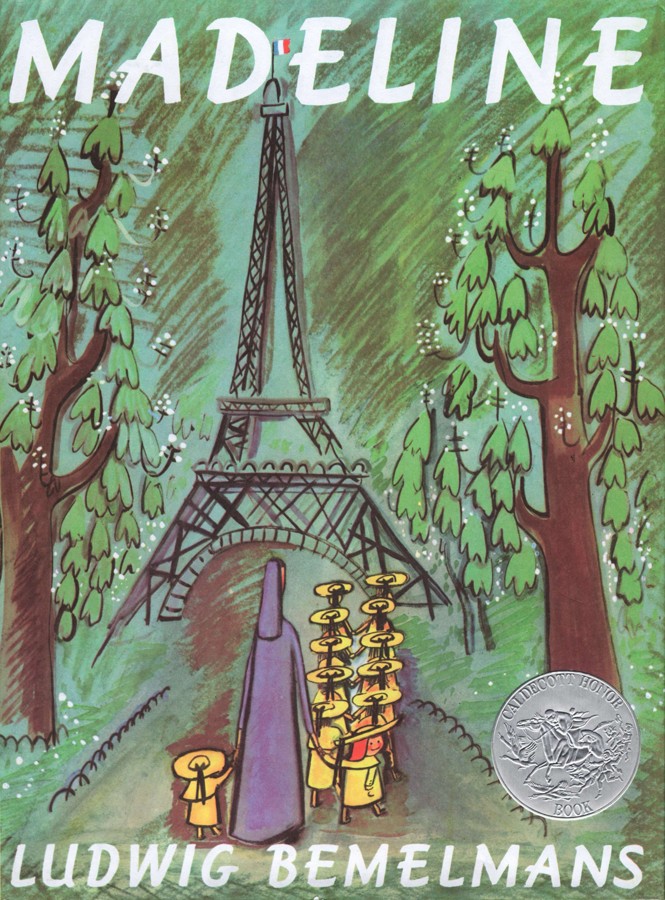

Madeline

written and illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans

1939

Oh, the drama of Madeline. The illustrations are big and colorful, leaving just a sliver of room for the words at the bottom of the page—irregular, sometimes-rhyming meter that adjusts to the action. The book’s “twelve little girls in two straight lines” have enviable daily lives: They take a rainy-day stroll by Notre-Dame, walk across the Seine, and go ice-skating outside Sacré-Coeur. One night, Madeline, the boldest of the group, is whisked off in an ambulance for an appendectomy. When the other girls visit her in the hospital, they’re jealous. She has toys and candy from her dad, and a cool scar! They want to have their appendix out too! This is the book’s sharpest and funniest insight into how kids see the world. What child hasn’t begrudged a classmate with a cast that everyone signs, or a sick sibling who gets to stay home from school, watching cartoons?

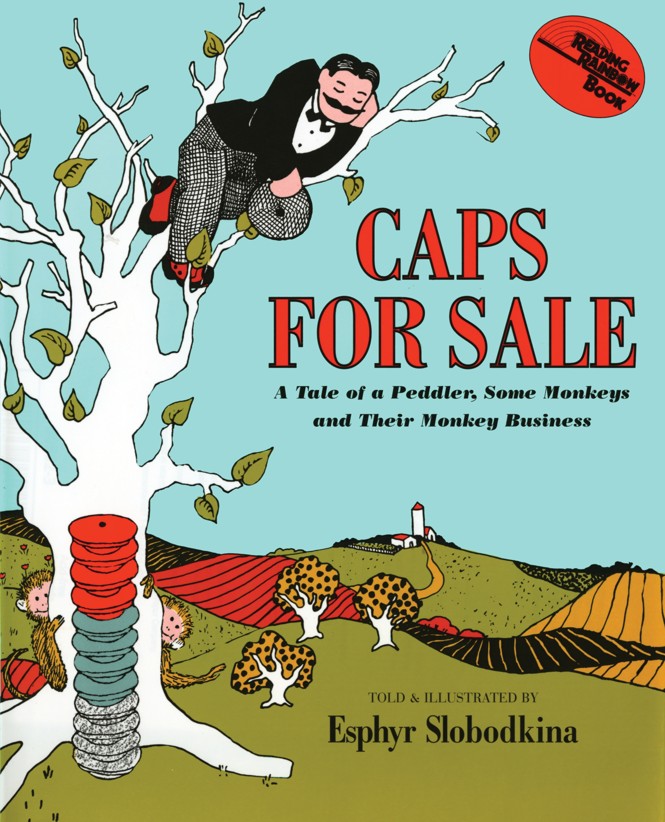

Caps for Sale

written and illustrated by Esphyr Slobodkina

1940

One of the first, and easiest, things you can do while reading a book with your child is get them to shake their fists. Caps for Sale, based on an old folktale, will help you pull that off: Its slow build, as a peddler has his inventory continually stolen by a band of monkeys, leads to a satisfying end, when he tricks them and gets his hats back. It’s told at a methodical pace that benefits the youngest reader, but the hint of genius appears when the man angrily stomps and shouts at those avaricious monkeys—you can admonish them right along with him.

The Carrot Seed

by Ruth Krauss, illustrated by Crockett Johnson

1945

The little boy at the center of this simple story is stubborn. He has planted a carrot seed that no one in his family—his mother, his father, his older brother—seems to believe will sprout. Yet he continues to pull up weeds and water the ground, until one day, he is proved right—in a big way. The patience he displays is worthy, even mature, but what gives The Carrot Seed its backbone, and a bit of edge, is the boy’s old-soul doggedness, his insouciant assurance that something, in the end, will come of his efforts.

Goodnight Moon

by Margaret Wise Brown, illustrated by Clement Hurd

1947

I remember, in the middle of my umpteenth read of Goodnight Moon to my children, some questions bubbling up: What is Brown’s book about, anyway? Why are we saying goodnight to a bowl of mush? Why is there a mouse, and how is it faring in a room with two kittens? Just what exactly is going on in that great green room? But now, having successfully survived lots of bedtimes, I know that the book is about vibes—about beauty and setting down the chaos of the day. It’s timeless, even in a world with fewer and fewer analog clocks.

Blueberries for Sal

written and illustrated by Robert McCloskey

1948

The plot of Blueberries for Sal should not be understood literally, because children should not follow fully grown brown bears through the wilderness. What does feel realistic, though, is the idyllic pleasure of a day spent with your mother, foraging for fruit without a care in the world. Sal, the heroine of McCloskey’s classic, is joyously committed to hanging out; for her, picking blueberries is an added bonus to the sunlight, the hills, the grass. That she confuses the bear for her mother—and that, accordingly, a bear cub confuses Sal’s mother for her own—exemplifies the book’s beautiful kid logic: Nothing can go wrong when you’re having a nice day outside. And despite one’s instinctive concerns about the bear, all is well in the end as both families are reunited and head home having picked their fill.

Harold and the Purple Crayon

written and illustrated by Crockett Johnson

1955

Among the barrage of flashy, colorful children’s books available today, Johnson’s minimalist line drawings practically whisper: Each page is stark white, except for the grayscale Harold and the objects he draws with thick, purple lines. In Harold’s dreamland, he cannot walk until he draws the road himself; he cannot eat until he draws his own pies. In this way, the story follows straightforward toddler reasoning, and ends up playfully illustrating cause and effect. The best part of the book is that its world is built entirely by a single child, sending a message that’s charming for readers of any age: Adventure can be available to anybody who thinks to seek it.

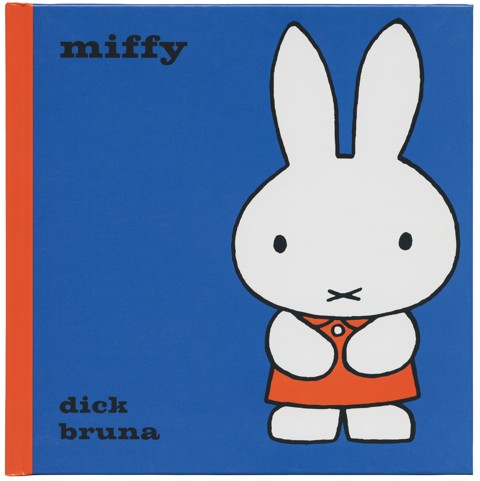

Miffy

written and illustrated by Dick Bruna

1955

Bruna’s Miffy (Nijntje in the original Dutch), the white rabbit with the X for a mouth, is by now as famous for being a design icon as she is for being a literary character. (You’d be hard-pressed to find a high-end museum gift shop that Miffy isn’t hopping through.) But the books themselves, with their pleasing sans-serif text, bold colors, and blocky shapes, should not be overlooked. Through Miffy, Bruna was not merely telling stories but creating objects to admire—this is most obvious, I would argue, when they’re in the chubby hands of a baby who’s captivated by their charm.

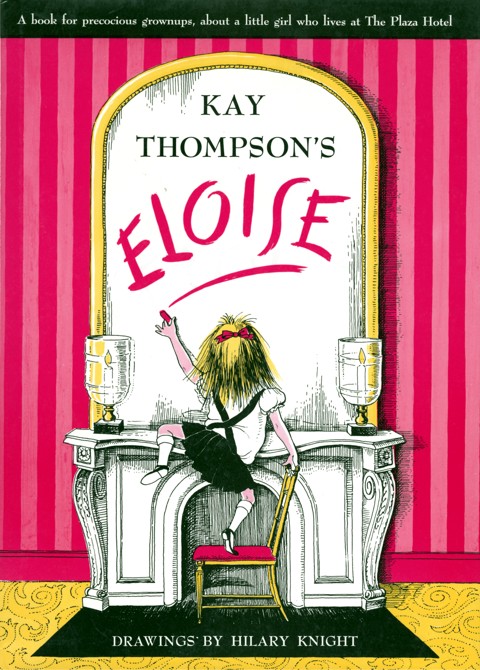

Eloise

by Kay Thompson, illustrated by Hilary Knight

1955

Eloise is surely the biggest brat in picture-book history. Few children would want to be her friend—she’s too bossy, marching belly first around the Plaza Hotel as if she’s the only kid in New York City. But what a delight it is to read about her as she presses all of the elevator’s buttons, upsets a waiter’s trays, and demands that room service “charge it please.” She has to help the busboys, she has to braid her turtle’s ears, she has to call her mother long-distance because—well, never mind, don’t worry about her mother. Who needs a mother when you’ve got a nanny and a turtle and the Plaza Hotel, where you’re never, not for one moment ever, even a little bit bored? What better book is there for an ordinary child to enter, and then—enchanted, exhausted, and obscurely sad—leave behind?

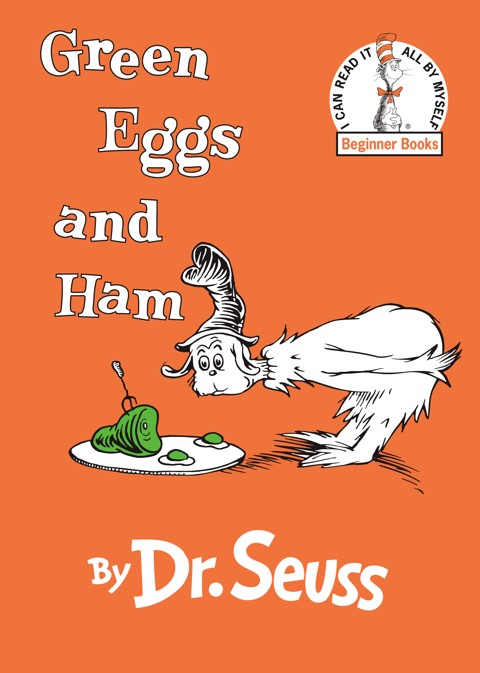

Green Eggs and Ham

written and illustrated by Dr. Seuss

1960

Theodor Geisel, one of the most rhythmically inventive writers in the English language, wrote more than 50 books for children. The works he left behind are complicated: Some Seuss drawings are clear racist caricatures; in 2021, the company that controls his estate ceased publication of six books that invoke ethnic stereotypes. Among the many that deservedly endure—tales of Horton and the Grinch and Bartholomew Cubbins—Green Eggs and Ham is arguably the best. As Sam-I-Am and the finicky narrator argue over the palatability of familiar but radioactively colored food, they embark on a propulsive journey—inside a car that runs up a tree, then on top of a train, through a tunnel, and onto a boat and into a teeming sea. Few books can so effectively build memory and delight through sheer accumulation: This one uses only 50 words (49 of them monosyllabic).

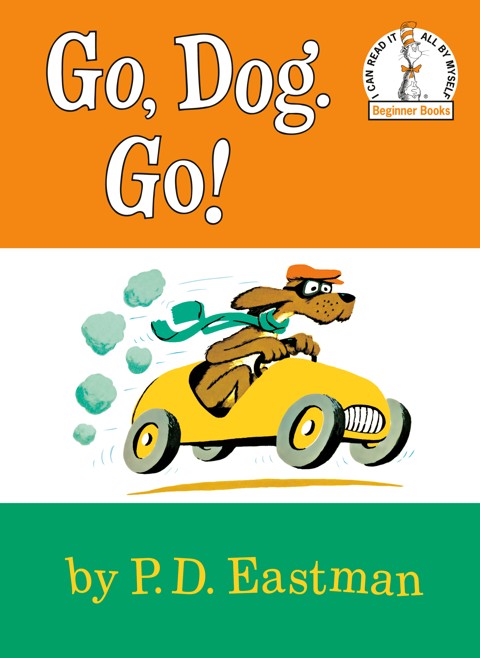

Go, Dog. Go!

written and illustrated by P. D. Eastman

1961

Go, Dog. Go’s minimalist pages feature mesmerizing, colorful line drawings and a perfunctory amount of text. Eastman doesn’t need much more than that to conjure a lively world of canines, in which a green dog pilots a helicopter over a tree, two blue dogs play paddleball on top of a blimp, and a pink poodle flirts with her dapper yellow acquaintance. The storytelling is specific, the artwork slightly surreal, and the total package nuanced—and often hilarious—enough to zoom readers through the pages.

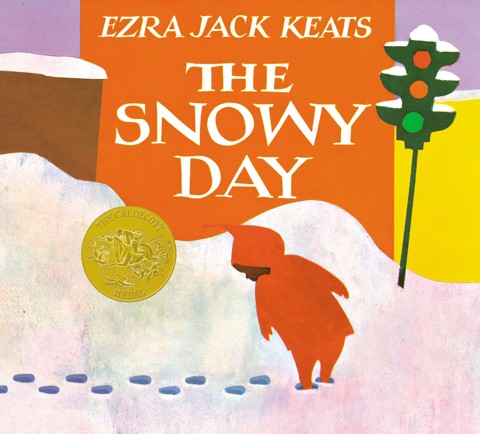

The Snowy Day

written and illustrated by Ezra Jack Keats

1962

One condition—and opportunity—of a genre made for open, unformed minds is that it tends to focus on the fantastical. The Snowy Day is not that kind of book. This is a plainspoken chronicle of an ordinary day in an ordinary city, rendered in simple collaged art and language that feels as hushed, spare, and exquisite as a snow-dusted street. Peter wakes up, romps around in his red snowsuit, builds a snowman, stashes a snowball in his pocket, and is confused when it disappears. The book, written in the midst of the civil-rights movement, was one of the first full-color picture books to feature a Black child as the main character, but that’s only part of what makes it special—The Snowy Day channels a child’s ability to find wonder in the mundane. It is assured in its approach and respectful of its young audience. Sometimes real life is fantastical enough.

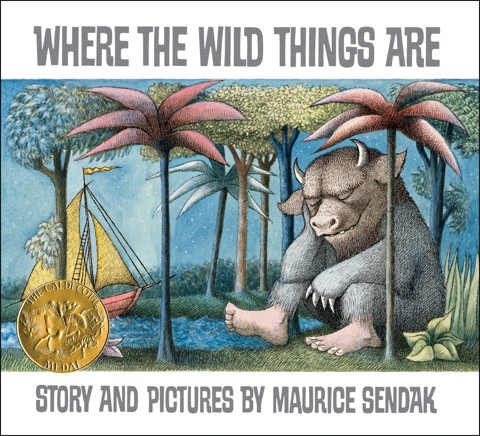

Where the Wild Things Are

written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak

1963

Max has been bad: He menaced the dog and threatened his mom, and so he is sent to bed without dinner. “That very night in Max’s room a forest grew,” Sendak writes, and suddenly we are off in a tantrum-driven fantasia, the most memorable of the author’s feral tales. A wild thing rises from the sea, flaunting its claws, but Max isn’t scared. Here the bad boy is king, and the monsters can’t take their eyes off him. Still, he is lonely, and he wants to be “where someone loved him.” As in all of the best stories, there is no moral here, only a threat of punishment, a reprieve, and a promise: that misbehaving children are still loved. When he wakes from his dream, Max sees that his mother has brought him dinner after all—milk, soup, and a fat slice of cake.

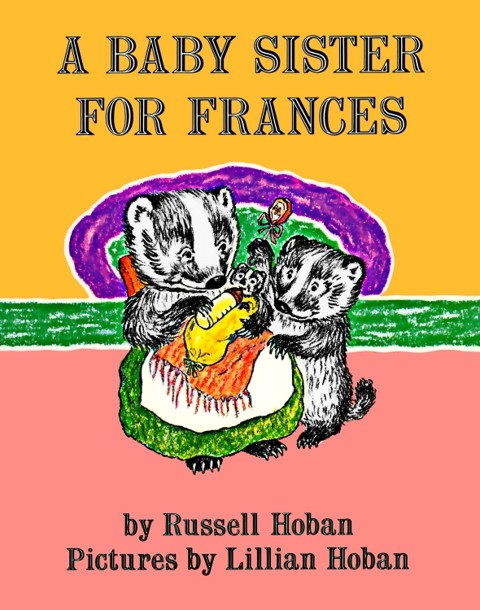

A Baby Sister for Frances

by Russell Hoban, illustrated by Lillian Hoban

1964

Hoban’s six-book Frances series—published from 1960 to 1970 and illustrated first by Garth Williams and then by the author’s wife, Lillian Hoban—portrays a sweetly schlumpy family of badgers to love and learn from. They model a crucial secret to transforming parent-child interaction: Don’t badger. When navigating trouble, encourage playful imagination instead. Mother and Father, low-key pros with a quiet sense of humor, are abetted by (and abet) their spirited firstborn, Frances. Her go-to habit when she confronts a problem (in this case, being sidelined by a baby sister’s arrival) is to rhyme her way out of it in funny verses. Big sisters better not sulk under the dining room table, she’s soon singing, “because everybody misses them / And wants to hug-and-kisses them.” She’s not quite pleased with that last rhyme. Her parents “like it fine.” The family cuddle is adorable. You’ll never think of the word badger (skunklike, needling) the same way again.

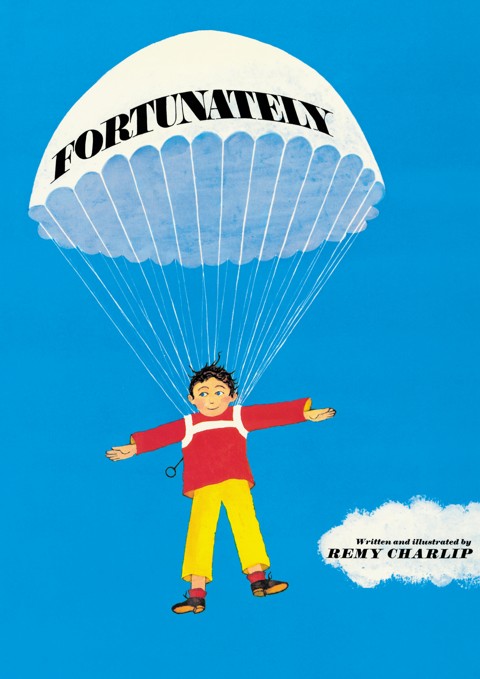

Fortunately

written and illustrated by Remy Charlip

1964

Ned is trying to get to a surprise party, but his fortunes keep flipping back and forth between luck and disaster. When he falls into shark-infested waters, for example, he swims away easily—then finds himself in front of a pack of hungry tigers. Fortunately is a crowd-pleasing romp full of hilarious twists; it also serves as a helpful reminder that, even when things seem like they can’t get any worse, there may be a pleasant surprise waiting just around the corner.

Minh Lê

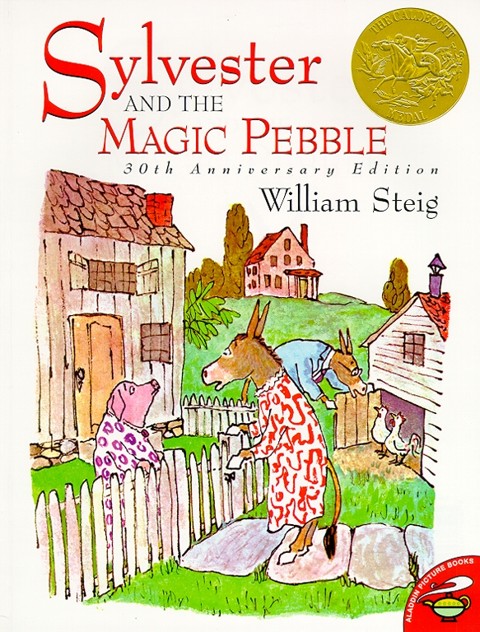

Sylvester and the Magic Pebble

written and illustrated by William Steig

1969

Sylvester is a donkey who—in a moment of desperation—uses a magic pebble to turn himself into a rock. Then, alas, he is incapable of undoing his wish. Sylvester’s parents end up picnicking on the boulder that is their son, wishing he was there with them. And, in one of the most piercing, intuitive moments in children’s literature, Sylvester calls out to his parents, “Mother! Father! It’s me, Sylvester, I’m right here.” Steig’s tale of being lost and found is funny, unpredictable, and moving.

Kate DiCamillo

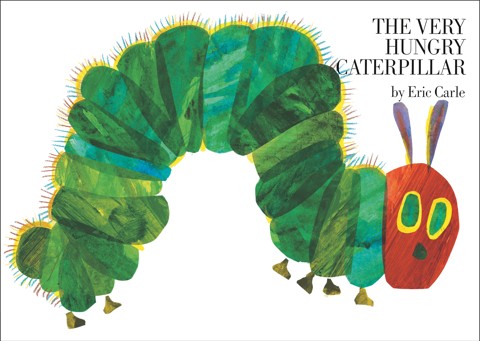

The Very Hungry Caterpillar

written and illustrated by Eric Carle

1969

I have long argued, only somewhat jokingly, that Carle’s magnum opus functions best as a paean to the healing properties of salad. A tired, hungry caterpillar wakes up one morning with an insatiable appetite, and munches through every kind of cuisine imaginable, leaving behind literal holes in the pages. It’s a never-ending delight to plough, with the caterpillar, through all of the food he eats: salami, a lollipop, cherry pie, sausage, a cupcake, watermelon. His massive stomachache is inevitable. But something manages to soothe our engorged friend: a simple dinner of one green leaf. Carle takes advantage of a natural twist ending to wrap things up, and our chubby little caterpillar becomes a big, beautiful butterfly.

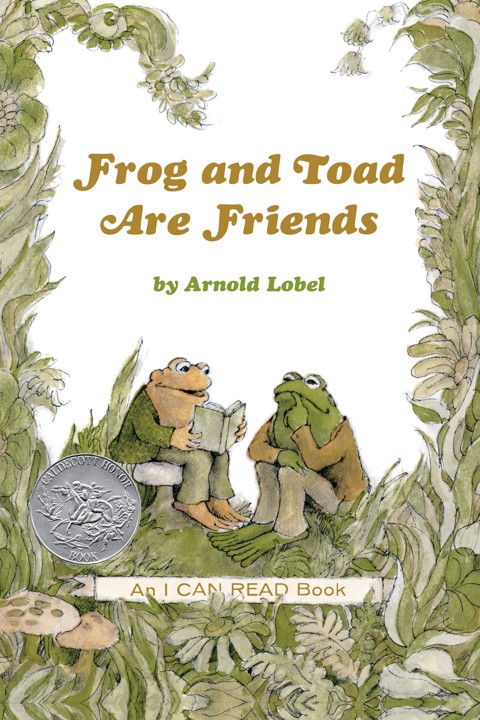

Frog and Toad Are Friends

written and illustrated by Arnold Lobel

1970

This book is termed an “easy reader,” but in truth, it is poetry. Lobel’s introduction to his beloved woodland pair, whose many books of adventure have endured for more than 50 years, is a lyrical meditation on the joys and challenges of friendship. It is wonderful to read aloud, and wonderful to hear—again and again and again.

Kate DiCamillo

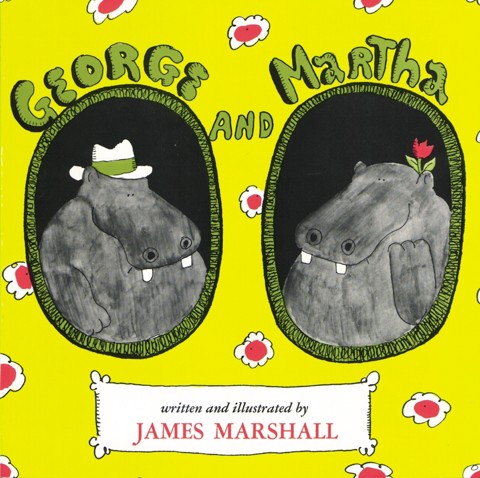

George and Martha

written and illustrated by James Marshall

1972

When Marshall created the well-meaning but bumbling hippos George and Martha in the early 1970s, he named them not after the first U.S. president and his wife but rather in tribute to the vicious marital antagonists of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. His hippos are much sweeter, but their stories are all about conflict between two best friends, evinced by examples children can understand: Martha is furious when George is too busy to see her; George thinks Martha looks in the mirror too much. Their relationship persists across seven books and through all of their farcical minidramas because, as George says, friends “always look on the bright side and they always cheer you up.”

Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day

by Judith Viorst, illustrated by Ray Cruz

1972

This title is not an overstatement. Alexander does, in fact, suffer a long series of indignities: gum in his hair, no toy in his cereal box, no dessert in his lunch box, lima beans for dinner. You can hear his frustration in Viorst’s narration, and see it in Cruz’s black-and-white illustrations—Alexander’s folded arms and scowl on the first page and his mouth-wide-open yelp midway through the story are particularly vivid. What makes this book transcend other children’s stories about bad moods and bad days is that it takes a Seinfeld-ian, “no hugging, no learning” approach to Alexander’s unhappiness. Our hero is still ranting as he goes to bed. (His night-light burned out! He bit his tongue!) We don’t see him cheer up or look on the bright side. Instead, we close with a bit of clear-eyed, motherly commentary: Some days are just bad. The end.

Where the Sidewalk Ends

written and illustrated by Shel Silverstein

1974

Silverstein is almost certainly the only author on this list who at one point lived in the Playboy Mansion. He was a weirdo and a hedonist and a goof—who better to capture a child’s predilections? In this collection of poetry, accompanied by scribbly illustrations, he steps into a universe where rules are meant to be broken and lessons are not always learned. This is a place where a plunger can be a very fetching hat, and a little girl can eat an entire whale if she just tries her best for as long as it takes (89 years, as it turns out). Where the Sidewalk Ends is genuinely funny, sometimes darkly so, and profoundly imaginative—the product of a singular mind.

Cars and Trucks and Things That Go

written and illustrated by Richard Scarry

1974

The title, like Scarry’s comic-strip-inflected illustrations, strikes a fast tempo. The vibrant cover is crowded with vehicles, and their animal drivers and passengers are in a hurry. Now open the oversize book, big enough to cover two laps. You’ll find yourselves hurtling along, too, tearing a page here and there in your rush. The eye-catching traffic streams left to right across both pages, as Ma, Pa, Penny, and Pickle Pig—stuffed into a red convertible VW bug—careen toward the beach for a picnic. A car shaped like an alligator, a five-seater pencil car, a broom-o-cycle, everything labeled: So silly, right? But the best part is pausing. The truck-obsessive in the family can bliss out on the road-construction array (rock crusher, tamper-downer, asphalt mixer, and lots more). In all the commotion, can you spot tiny Goldbug, cleverly hidden by Scarry? Only if you slow down. You’ll also notice lots of other things that go (and don’t).

Strega Nona

written and illustrated by Tomie dePaola

1975

Oh, Strega Nona! No other witch in all of literature can compare to the one who stands, eyes closed and arms outstretched, like a maestro over her magic clay pot. DePaola offers much to adore: soft-brush earth tones; the reverence with which the villagers twirl their forkfuls of pasta; Big Anthony, that poor doofus; and of course all of that spaghetti, cresting across the pages in waves. But most of all I adore Strega Nona herself—a legend in watercolors, radiating confidence and good humor in the face of chaos. A bewitched pot is nice, but Strega Nona’s serene self-satisfaction is the true magic.

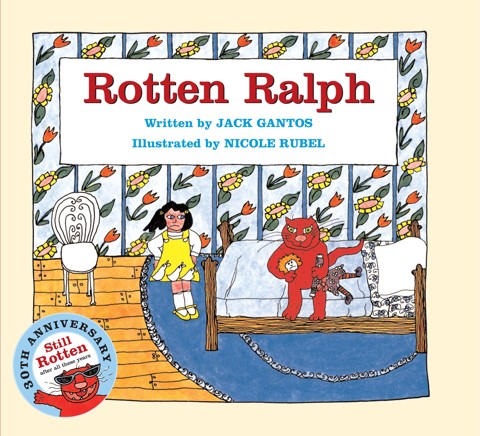

Rotten Ralph

by Jack Gantos, illustrated by Nicole Rubel

1976

Like all good cats, Ralph is a menace. He harasses his owner, Sarah—ruining her parties, cutting down tree branches she’s swinging from—but, like all good cat owners, she loves him anyway. Rubel’s wacky, Matisse-inspired illustrations show Ralph to be more human than pet. He sits upright in chairs, rides a bike, and catches birds with a net. Of course, Ralph is due for a comeuppance: When his behavior becomes too much for Sarah’s parents, they purposely leave him behind at the circus. His journey back to Sarah is briefly harrowing. But it’s a credit to Ralph—and to Gantos’s lines—that once home, Ralph goes right back to his old, rotten ways, making him one of the few perfectly unrepentant antiheroes in children’s literature.

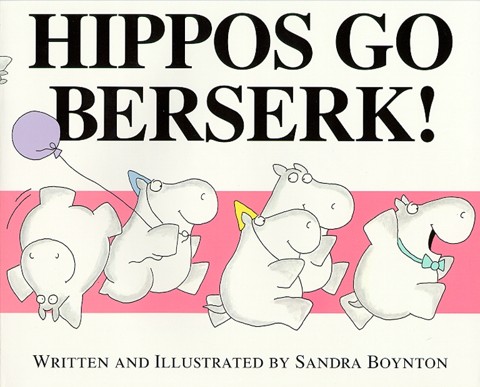

Hippos Go Berserk!

written and illustrated by Sandra Boynton

1977

Hippos Go Berserk!, a sterling example of Boynton’s comedic genius, has the subtitle “A wild counting story.” “One hippo, all alone, calls two hippos on the phone,” it begins, and each page introduces another attendee to a gathering being planned in real time, until 45 of them crowd an all-night cocktail party. Then come the visual gags: There’s a hippo’s version of Whistler’s Mother, a hippo upside-down, and one guest, a classic spiky-furred grinning Boynton beastie, who consistently eludes the count. As the hippos gradually leave, little creature in tow, Berserk shows that even basic arithmetic can be an act of imagination, rather than rote repetition—and it cleverly reminds adult readers that the most familiar exercise can invite unexpected images into the mind.

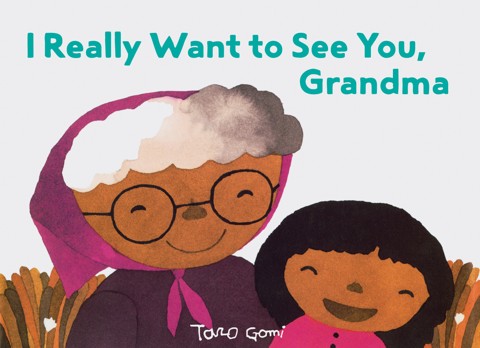

I Really Want to See You, Grandma

written and illustrated by Tarō Gomi

1979

Trains and buses are the building blocks of many children’s imagination, and in I Really Want to See You, Grandma, this prolific writer and illustrator gets them exactly right: minimal detail, muted colors, irregular lines and shapes. These familiar conveyances are put to slapstick effect here, as Yumi and her grandmother go through a series of more and more desperate attempts to meet up. Gomi’s tender story is so satisfying because as it celebrates intergenerational friendship, it sets up a pleasing symmetry between grandparent and grandchild. Their bond’s thrilling, kinetic power is made clear by the climax: a joyous collision between Yumi on a scooter and Grandma on a motorbike.

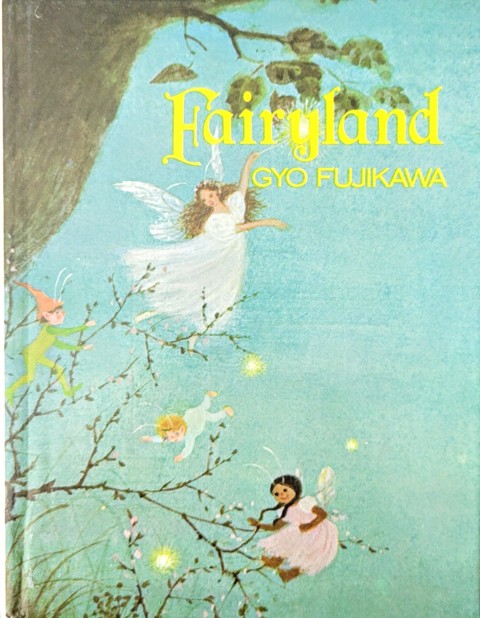

Fairyland

written and illustrated by Gyo Fujikawa

1981

What you notice first about Fujikawa’s illustrations is that they are equal parts stunning and sweet. My favorites are in this book (which, though out of print, can be found with a little luck online), along with Babies and Baby Animals, both from 1963, and Oh, What a Busy Day!, released in 1976. Every detail is meticulous: the wrinkle of fabric on a sleeping infant’s nightgown, the blend of colors in a dusk sky, the sparkle of fireflies rising up across the page. Many of Fujikawa’s illustrations are irresistibly cute, yes, but she also manages to capture the natural world as seen through the eyes of a curious and adventurous child: The trees are gigantic, the light is always changing, and wildflowers grow taller than your head. Fairyland is a story about actual fairies, but the title is also a good descriptor for the universe Fujikawa created through the beauty of her entire oeuvre.

Miss Rumphius

written and illustrated by Barbara Cooney

1982

When this book opens, Alice Rumphius is a little girl with three goals: to visit faraway places, to live by the sea, and to make the world more beautiful. She accomplishes the first two without much trouble. The third, though, proves trickier. “The world is already pretty nice,” she thinks. But later, Miss Rumphius spends a long season bedridden, and when she is finally well enough to go outside again, she sees the world anew. Eureka: She can plant flowers that turn her town’s hillsides breathtaking shades of blue, purple, and pink. This book understands that suffering can clarify one’s vision and purpose. The story closes with Miss Rumphius telling her great-niece that she, too, must make the world more beautiful, and the niece, echoing the uncertainty her aunt once felt, saying, “I do not know yet what that can be.” It’s a gorgeously bittersweet ending. We know she’ll find her calling; we don’t know what she’ll have to go through to discover it.

Everett Anderson’s Goodbye

by Lucille Clifton, illustrated by Ann Grifalconi

1983

Grief doesn’t spare anyone—even children, especially children, whose open hearts and brand-new brains may be least equipped to deal with it. Everett Anderson’s Goodbye uses Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief as the waypoints through which a young boy must pass in order to come to terms with his father’s death. This is a useful book, but it isn’t a didactic one: Clifton, a world-class poet, seems to be much less interested in instructing than in observing her young protagonist’s emotions in all their contradiction and depth. Her story is simple yet evocative: Everett is sad; Everett is angry; Everett is confused. Everett cries big, fat saltwater-pearl tears and stares out the window. He fights with his mama. He dreams of his daddy.

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie

by Laura Numeroff, illustrated by Felicia Bond

1985

A boy offers a mouse a chocolate-chip cookie. The mouse asks for some milk. From there, things devolve. The mouse would like a straw, and a napkin, and could he please have a tiny bed too? This story has endured for 40 years partly because it lets kids live the experience of having every impulse accommodated—and possibly because it gives them a taste of how parents feel about their constant demands. Numeroff’s metaphor has been used to argue against welfare, and it’s invoked in the 1990s thriller Air Force One as a reminder of why you shouldn’t negotiate with terrorists. (Seriously.) But to interpret this book as a cautionary tale against giving anyone what they ask for does it a disservice. The enthusiastic mouse doesn’t actually do anything bad. Rather than being a slippery slope to ruin, his story is as full circle and satisfying as a cookie.

Annie Bananie

by Leah Komaiko, illustrated by Laura Cornell

1987

Until I reached the second grade, a girl named Sam was a major character in my tiny existence. She was one of my first best friends—and then that summer her family moved away, plucking her out of my life. I wish I’d had Annie Bananie. The book offers no explanations for why a pal might relocate, nor any promises that friendship lasts forever; it’s just a kid’s primal scream of betrayal. When the narrator learns that her friend, the titular Annie B., is leaving town, she’s indignant—posing pointed theoretical questions such as “Do you think it’s good / leaving your whole neighborhood?”—but also tender, aware that this particular girlboss, who makes her tickle bumblebees and tie her brother to a tree, will not be replaceable. Neither, she hopes, will she. “When you are in bed at night,” she says, ending on a note both sweet and vaguely threatening, “remember … you’ll never ever ever never ever ever never find another friend like me. Will you?”

Faith Hill

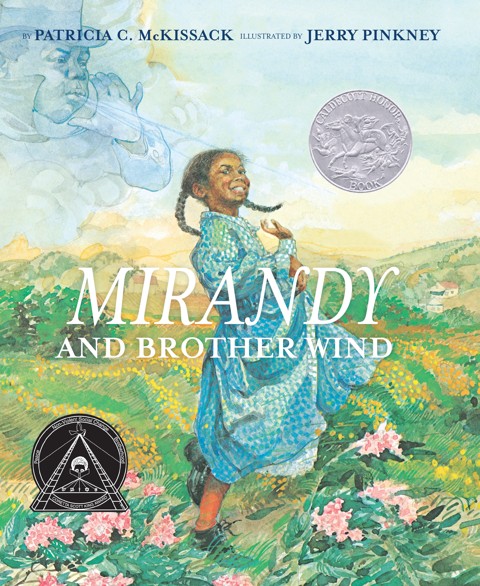

Mirandy and Brother Wind

by Patricia C. McKissack, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney

1988

With its combination of rich watercolors and snappy dialect, McKissack’s story, set in the rural southern community of Ridgetop, welcomes its readers with bombast and generosity. It’s spring, which means the junior cakewalk is coming up—and Brother Wind is “high steppin’” his way into town. Mirandy’s mom tells her that “whoever catch the Wind can make him do their bidding,” so Mirandy hatches a plan: She’ll find Brother Wind and make him her dance partner. “Can’t nobody put shackles on Brother Wind, chile,” her grandmother warns her, but she persists until she finally corners him in a barn. Yet in the end, after she hears some girls making fun of her friend Ezel, she picks him for the dance. And she surprises everyone in town when she and Ezel take the cake—with a little help from Brother Wind.

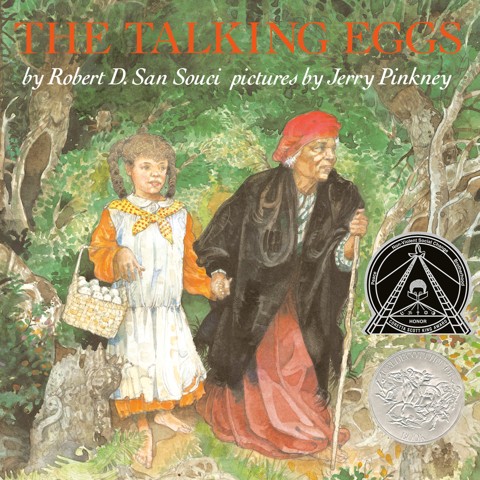

The Talking Eggs

by Robert D. San Souci, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney

1989

The Talking Eggs is a retelling of a Creole folktale about a pair of polar-opposite sisters: kind, smart Blanche and shallow, cruel Rose. They separately encounter a mysterious old woman with enchanted eggs that reveal either treasures or nightmares; each sister gets what she deserves. San Souci, who in the course of his career adapted more than a dozen folktales from various cultures (Disney’s Mulan comes from one of his books), tells this story in colloquial language that recalls the oral tradition it came from, making the book a pleasure to read aloud. But Pinkney’s absorbing watercolor illustrations are the real treat. Every one is satisfyingly dense, though the most exciting pages feature the magical beings to whom the old woman introduces the sisters—chickens that sing like mockingbirds; rabbits dressed in finery, square-dancing in the moonlight.

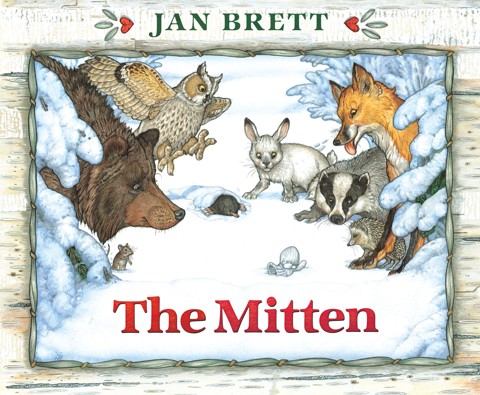

The Mitten

written and illustrated by Jan Brett

1989

Brett’s cozy adaptation of a Ukrainian folktale is an homage to craftsmanship. Little Nicki jumps onto the page, drawn fastidiously, in his handmade red hat and embroidered tunic. His baba, surrounded by skeins of dyed wool in front of a gorgeously painted fireplace, is knitting the white mittens Nicki has begged for, even though she knows he’ll lose them if he drops them in the snow. Any adult can anticipate what happens next. Brett’s detailed illustrations make the warm, snuggly, left-behind mitten irresistible. Soon she’s depicting a menagerie of forest animals squeezing inside, and not a detail is omitted: See the hedgehog’s individual spines poking out between stitches, for example. Baba’s handiwork is so strong that even a bear wiggles his way in before a ferocious sneeze sends the mitten flying back home, abetting maybe the luckiest evasion of an “I told you so” in kids’ literature.

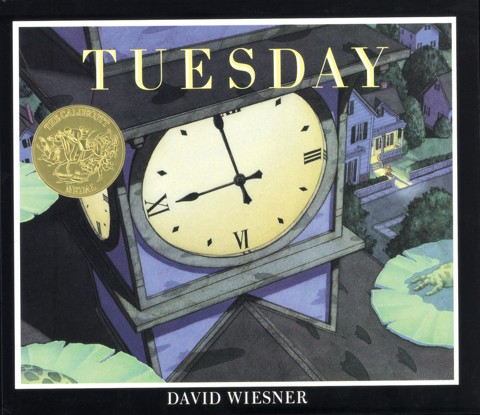

Tuesday

written and illustrated by David Wiesner

1991

This weird and wonderful picture book gives adults and children heaps of opportunities to be curious together. With essentially no text, Wiesner creates multiple engaging, rich storylines about bizarre occurrences happening on a Tuesday, all of which are brought together in the end. For me, this initially posed a challenge—what in the world are you supposed to do without words to read out loud?—but Tuesday actually inspires a collaborative reading experience, in which adult and child can co-create the backstory.

Dipesh Navsaria

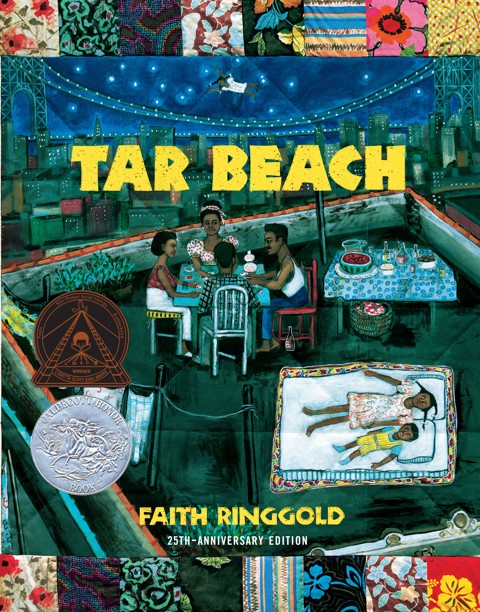

Tar Beach

written and illustrated by Faith Ringgold

1991

Over more than half a century, Ringgold vividly captured the Black American experience in paintings, quilts, sculptures, costumes, and children’s books. Her style was well-suited to this last genre; Tar Beach, Ringgold’s first picture book, pops with an expansive color palette and unselfconscious illustrations that call to mind those found in elementary-school classrooms. The story, which follows the young Cassie as she pursues her dream of taking flight from her Harlem apartment, is similarly bold, and her adventure offers insight into the aspirations of working-class New Yorkers in the late 1930s. What really makes the book sing, though, are the quiltlike patterns that border each page, inviting readers to explore the rest of Ringgold’s deep, moving body of work.

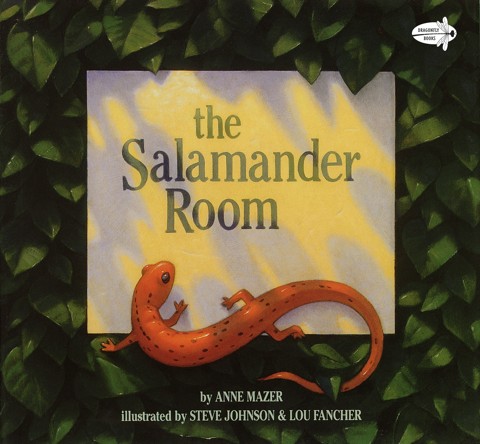

The Salamander Room

by Anne Mazer, illustrated by Steve Johnson and Lou Fancher

1991

When children stumble across any sort of delightful animal, they almost always want to bring it home. But many wild creatures have died in the loving hands of an unguided little one, and so I love The Salamander Room and think all parents should share this story with their kids. The book’s gorgeous, soulful illustrations depict a salamander, a young boy, and the natural world he comes to know. When the boy’s mom asks gentle questions focusing on the amphibian’s needs, the reader’s consciousness moves from the novelty of acquiring a pet to the responsibility of keeping that creature healthy and happy—which frequently means returning it to its place in a beautifully complex ecosystem.

Janell Cannon

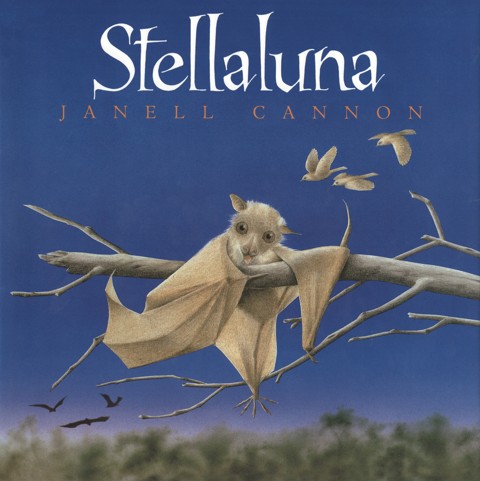

Stellaluna

written and illustrated by Janell Cannon

1993

Cannon has said that she chose a baby bat to be the hero of her story because she hated to see the creatures “being misunderstood and mistreated by humans, out of fear.” Cannon’s astonishing pictures of wide-eyed Stellaluna are easy to love, but the bat is still in for a hard time: After she’s separated from her mother, she falls into a nest full of baby birds and tries to adopt their ways—eating bugs instead of fruit, sleeping upright instead of upside down—because Mama Bird sternly tells her that batlike behavior is a bad influence. But when Stellaluna is reunited with her mother and fellow bats, her bird friends, who can’t see at night, are the ones who don’t quite fit in. The baby-animal cultural exchange teaches all of them the valuable lesson that “different” doesn’t mean “wrong.”

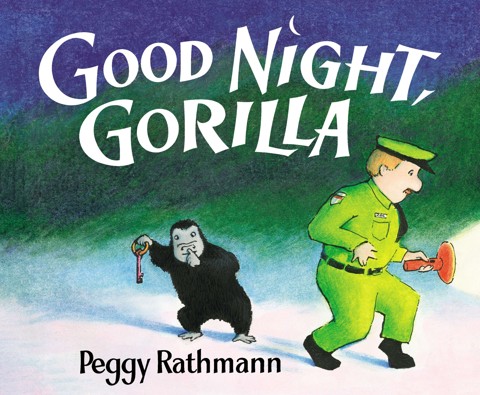

Good Night, Gorilla

written and illustrated by Peggy Rathmann

1994

Sight gags abound in this classic goodnight book, which drops the calm and soothing mode of the genre in favor of the screamingly funny. After an utterly oblivious human security guard is hoodwinked by a clever zoo gorilla, a group of animals roam free behind his back—and end up snoozing in the guard’s own bedroom. Children may identify gleefully with the quick-witted, adult-outsmarting gorilla, who leads a revolution against bedtime.

Dipesh Navsaria

Bark, George

written and illustrated by Jules Feiffer

1999

As a cartoonist for adults, Feiffer discovered pleasure in everyday haplessness; here, a parent’s exasperation becomes a ticklish, surreal vision. Feiffer draws a puppy named George who, when commanded to bark, instead meows, oinks, or moos. A rubber-gloved vet investigates, pulling a cat, pig, and cow out of George’s tiny body. His desperate mother, a dog who just wants to see her puppy be himself, is rewarded, finally, with an “Arf!” But Feiffer has one last punch line waiting for us. George opens his mouth, and out comes “Hello.”

Olivia

written and illustrated by Ian Falconer

2000

The titular piglet in Olivia gets up to a lot. She jumps rope, builds sandcastles, dances, runs, paints—and that’s not even counting the things she has to do, such as brushing her teeth and taking a bath. Falconer’s black, white, and red illustrations have so much life in them that they feel as if they could start moving at any moment. I remember being particularly transfixed by a spread involving 17 different outfits and tracing the outlines of a sweater and a gown with my sticky toddler finger. Olivia’s energy and curiosity can wear people out (and sometimes she wears herself out), but she gets to explore her talents and ambitions with the security of knowing she’s unconditionally loved.

Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type

by Doreen Cronin, illustrated by Betsy Lewin

2000

What parent doesn’t empathize just a bit with Farmer Brown? He’s simply trying to keep his livestock safe and fed when his cows get hold of a typewriter and start making demands. They want what? Electric blankets? The hens are cold too? But even if grown-ups sympathize with the management, this charmer of a book makes all of its readers feel solidarity with the chickens and cattle. When the barnyard crew strikes—no milk and no eggs until they get their blankets—they pull off probably the cutest possible unionization. Parents should just beware that the example can be contagious, and not only for the farm’s ducks. Tooth brushing and bathing might be at risk.

Beautiful Blackbird

written and illustrated by Ashley Bryan

2003

Stories adapted from traditional folktales generally come with a heavy-handed dose of moralizing that can feel preachy or dated or both. Beautiful Blackbird, based on a tale told by the Ila-speaking people of Zambia, skips lightly over those pitfalls through its skillful use of both pictures and words. Bryan’s paper cutouts create brilliant tableaus that invite interaction: Find that bird, trace those outlines, point out the black lines and spots. Occasional exclamations beg to be shouted in concert, and rhyming dialogue heightens the fun. The book, now considered a classic, prefigured many later titles about respect, community, and Black pride. Like all of the best picture books, Beautiful Blackbird first entertains, then enlightens; it operates via a kind of osmosis that seeps from page to brain and, eventually, to the reader’s heart.

Linda Sue Park

Michael Rosen’s Sad Book

by Michael Rosen, illustrated by Quentin Blake

2004

Rosen—the author of the poem “Chocolate Cake,” an indelible account of midnight treat-sneaking, and We’re Going On a Bear Hunt, the definitive saga of going under, over, and through—deals here with deep, real-life sadness. His son Eddie died, and now sometimes he’s sad even when he looks happy; other times, he writes, the sadness is “all over me,” and he looks especially gloomy. There are moments when he wants to talk about losing Eddie, as well as times when he doesn’t want to talk about it at all. His family won’t ever be the same, and sometimes this makes him angry. But in this frank, unpretentious book, Rosen tries to find ways of being sad that aren’t so painful. There are no silver linings here: Rosen will always miss his child, so all he can do is be honest. His straight-faced yet vulnerable account is something anyone whose sadness is “everywhere” can appreciate—even someone very young.

Kitten’s First Full Moon

written and illustrated by Kevin Henkes

2004

In black, white, and many shades of gray, this book turns on its head the idea that illustrations for children must be brightly colored. It will also introduce infant and toddler readers to the novelty of seeing a full moon that is forever seemingly just out of reach—and offer older children the satisfaction of predicting what Kitten will stumble into next. The narrative alternates between contemplative pauses and bursts of action, and I adore the way the certainty of the feline psyche collides with the reality of the world.

Dipesh Navsaria

Little Blue Truck

by Alice Schertle, illustrated by Jill McElmurry

2008

The most memorable aspect of this story, at least according to my own child, is the mud—which snares a busy, self-important dump truck first seen speeding past a toad, chicken, horse, sheep, and cow. The headstrong vehicle gets stuck in a pit and, having alienated the entire barnyard, cries out in vain for help. In drives the eponymous Little Blue Truck to save the day. Acting on his own, Little Blue Truck gets just as wedged in the mud, but Little Blue’s animal friends come together to push. The diminutive toad turns out to be the hero, because his tiny contribution makes the difference. A chastened dump truck realizes that “a lot depends / on a helping hand / from a few good friends”—and learns to be especially grateful for the smallest of the bunch.

We Are in a Book!

written and illustrated by Mo Willems

2010

We begin in medias res, with a wink. You, reader, and Piggie the pig are in cahoots, although you may not yet know the particulars. Gerald the elephant, Piggie’s dear friend, soon catches on: He and Piggie are being watched—and not just by any old snoop, but by you. We Are in a Book!, my household’s favorite entry in Willems’s Elephant & Piggie series, gleefully smashes through the fourth wall to show how words that sit humbly on the page can end up spurring a human to action. “I have a good idea!” Piggie says, realizing you’re probably reading aloud. “I can make the reader say a word!” This is so magical that Gerald becomes distraught when he realizes that the book must end. But fear not: At the close, Piggie and Gerald come up with a solution that encourages the fun to continue.

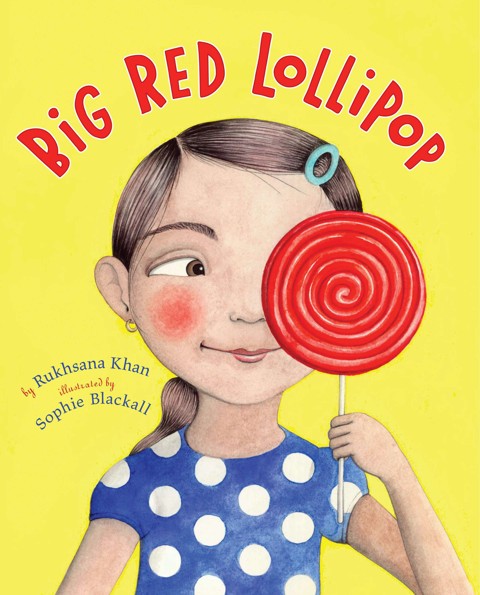

Big Red Lollipop

by Rukhsana Khan, illustrated by Sophie Blackall

2010

Big Red Lollipop understands that life isn’t always fair, and proves it by foregrounding the indignity of being the eldest child. Rubina knows that the invitation to her classmate’s birthday party didn’t come with a plus-one, and that bringing her annoying kid sister Sana, at her mother’s insistence, will surely lead to ostracism. (It does, and the party invites dry up for a while.) Nor does it help that Sana is a real pill: She acts like a baby; she gobbles her own candy, then steals Rubina’s share. But being a big sister isn’t just about keeping score, Rubina realizes later. When Sana gets her own invitation, Ami proposes that Sana take even littler Maryam along. Rubina implores Ami to let her go alone. Her altruism pays off, eventually, when Sana becomes less of a terror and more of a friend.

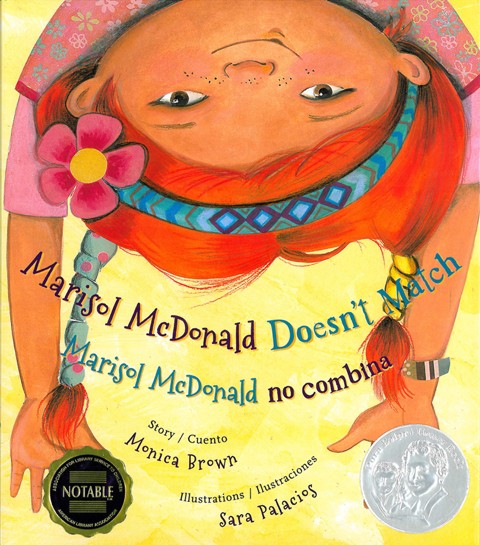

Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match

by Monica Brown, illustrated by Sara Palacios

2011

Marisol McDonald is a Peruvian, Scottish, and American girl who loves clashing patterns and peanut-butter-and-jelly burritos; she emphatically refuses to fit in any one category. Although her preferences are unconventional, this lovely book makes clear that Marisol’s tendency toward “mismatching” is, in fact, her most enviable trait. The story, told simultaneously in English and Spanish, shows what can emerge when seemingly disparate cultures, backgrounds, and tastes blend together, just as they do in Marisol’s family.

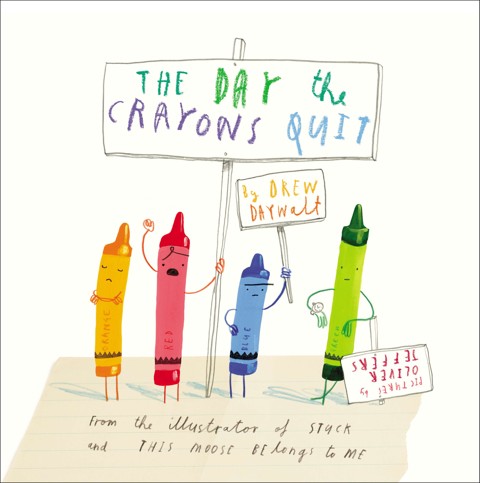

The Day the Crayons Quit

by Drew Daywalt, illustrated by Oliver Jeffers

2013

The Day the Crayons Quit is not just a book, but a piece of theater—it simply will not work unless you’re ready to reach deep into your cache of silly voices and commit to the bit. The premise: An assortment of crayons with serious workplace grievances have left a stack of letters for their owner, Duncan. Red crayon is tired of working holidays. Purple, the neat freak, is affronted at being used to color outside the lines. Yellow and Orange are mired in interpersonal conflict. Pink has a gender-discrimation complaint. The reader’s job is to take the visual cues—Red’s sweaty brow, Pink’s cross-armed pique—and summon the tone and diction to match. Do it right and you can expect a rapt audience (and perhaps a Tony Award in the mail).

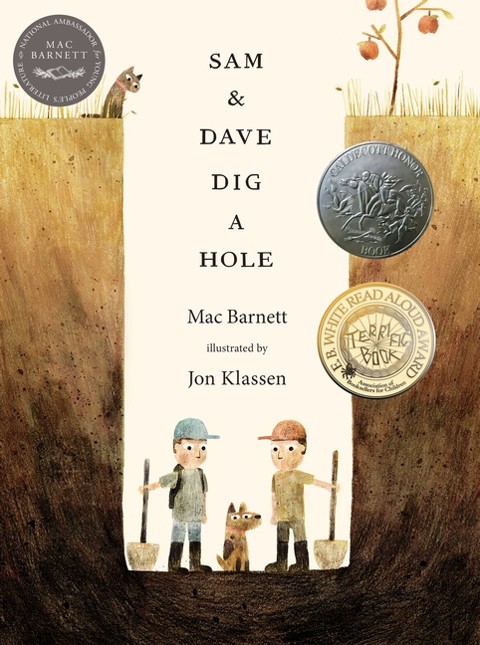

Sam & Dave Dig a Hole

by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen

2014

Here is the essence of the picture book: Words telling one story, art telling another. The reader watches these boys tunnel deep into the Earth, hunting for—and just missing—something spectacular. Your view conjures the satisfying whole.

Jon Scieszka

Grandad’s Island

written and illustrated by Benji Davies

2015

A child’s imagination functions as both a means of self-protection and a way of explaining the incomprehensible. In this subtle parable, a boy pays a visit to his granddad’s house, only to find him in the attic; quickly, they leave the room and its musty antiques behind for a massive ship, which whisks them both off to a tropical island—where Granddad decides he will stay forever. Davies’s story is about death, but what makes it so memorable (along with its timeless but casual artistry) is that it can be interpreted on several levels. Even a child who knows nothing about mortality can intuit its theme of loss; even a mournful grown-up can relish its sense of adventure.

Last Stop on Market Street

by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christian Robinson

2015

Leaving church with Nana on a rainy day, CJ resists their Sunday routine of taking the bus to the soup kitchen where they volunteer. “How come we don’t got a car?” he asks. Nana laughs off the question, then spends the ride pointing his attention to the people around them and the moments of connection they offer, encouraging him to enjoy the woman holding a jar of butterflies and the musician strumming his guitar. The bus, she’s telling him, has plenty to offer on its own terms. By the end of the ride, CJ isn’t focused on what he doesn’t have: He’s glad to inhabit the world he does.

The Sound of Silence

by Katrina Goldsaito, illustrated by Julia Kuo

2016

A perfect book for a hyperstimulated world: Goldsaito’s story, whose deep wisdom will linger long after you read it, follows a young boy searching a noisy city for the sound of silence. Imagine sitting down to a guided meditation led by Christopher Robin, and you’ll begin to understand its quiet magic.

Minh Lê

School’s First Day of School

by Adam Rex, illustrated by Christian Robinson

2016

“I don’t like school,” a shy little girl whispers during her very first class. “Maybe it doesn’t like you either,” the school retorts, as frazzled and huffy as any new kid. By cleverly transferring all of the apprehension surrounding a new academic year onto a brand-new edifice (with an oddly expressive front door), Rex not only soothes first-day jitters but slyly introduces young children to a theory of mind. No one—not even a building, maybe—wants to be torn away from the familiar and bombarded by clamorous strangers. But after the bell rings, Frederick Douglass Elementary can’t stop talking to the janitor about how much fun it was: One kid told a joke; there was a fun lesson about shapes; will the shy girl be back tomorrow? Maybe school isn’t so bad after all, even for school.

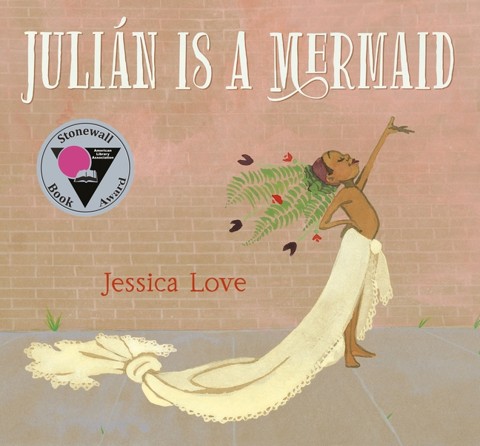

Julián Is a Mermaid

written and illustrated by Jessica Love

2018

From Julián’s vivid point of view, the imaginary blurs with the real. On the subway, inspired by a trio of glamorous mermaids, he imagines himself in an underwater expanse, where his puff of hair unfurls into a long mane and a school of fish give him a purple tail. At home, he chases this vision: Abuela’s lacy curtains become his fins; her fern and flowers, his tresses. When Abuela finds him in full mermaid splendor, she’s not pleased, and he tries to understand what he’s done wrong. But her frown is about the state of her apartment, not Julián’s dreams. She takes him to the beach to find a dazzling procession of sea life, evocative of Coney Island’s annual, gender-bending Mermaid Parade. “Let’s join them,” Abuela says. Where a child might see only an enchanting party, an adult will recognize that she’s showing Julián that the world has a place for him, whatever he wants to be.

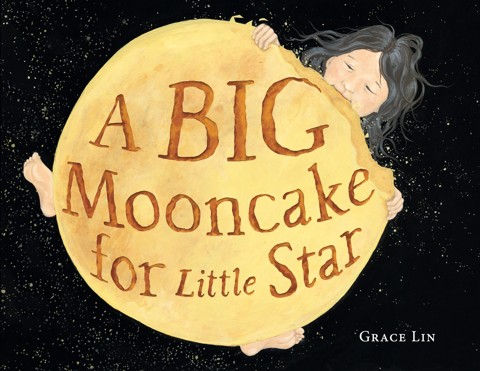

A Big Mooncake for Little Star

written and illustrated by Grace Lin

2018

Little Star’s mom has made a delicious mooncake and set it aside in the sky. This treat is so scrumptious—so tempting, so absolutely irresistible—that Little Star, who’s promised her mama she won’t touch it, gets up in the night to have just a teeny bite. She gets away with it, so she’s back again the next night, and the next, until the mooncake is whittled down to a half circle, and then a slim crescent, and then—oops. Once the whole thing is gone, Little Star and her mom need to bake a new one and hang it, whole and shining, among the stars. (One gets the sense, knowing that the moon will go through its phases all over again next month, that our protagonist hasn’t learned her lesson.)

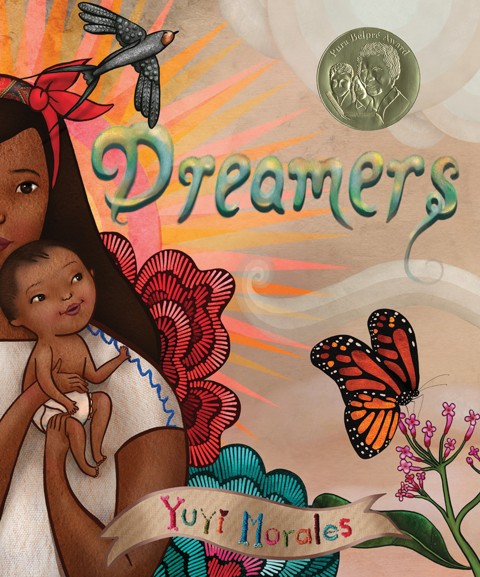

Dreamers

written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales

2018

A mother and son cross into the United States, where they find their way to a library that turns their world Technicolor: “Books became our home,” the mother notes, as they both learn English through reading. Dreamers, enlivened by dazzling images that combine acrylic paints and scanned photographs, is a picture book that is in part an ode to the power of picture books, told in swirling and poetic language. For Morales’s characters, immigration opens up an entirely new life, and reading widens it even further.

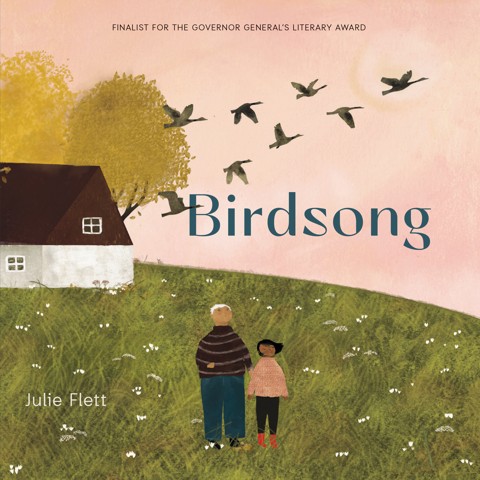

Birdsong

written and illustrated by Julie Flett

2019

Birdsong, a melancholy book of muted illustrations in which specks of white and pink represent the burst of spring flowers, is about change. Katherena must leave behind a place filled with family for a lonely house in the country, where she interacts with only her mother, her dog, and her elderly neighbor, Agnes. But Agnes becomes a steadfast friend, showing Katherena her garden and her pottery; in exchange, the girl shares her drawings and her Cree vocabulary with Agnes. (The book’s brightest pages show off the gallery of pictures Katherena later hangs in the ailing Agnes’s bedroom.) As the seasons shift, Katherena embraces her new home, even as she begins to understand that not everything can last forever.

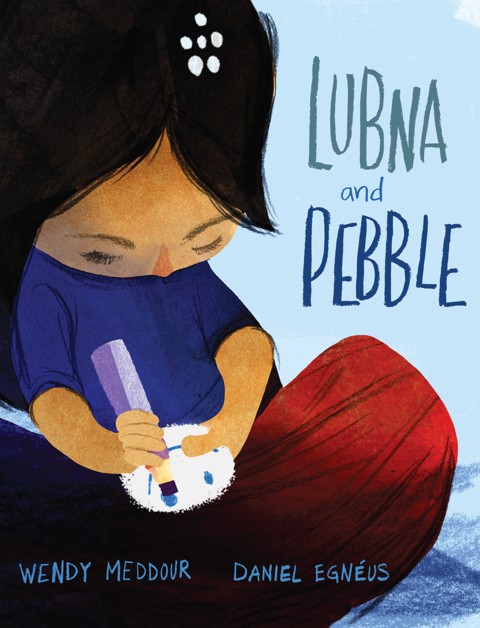

Lubna and Pebble

by Wendy Meddour, illustrated by Daniel Egnéus

2019

In Meddour’s understated, pleasingly illustrated tale, Lubna is going through something strange and scary: She and her family, now refugees, have had to leave their home behind. They arrive at a “World of Tents,” where lonely Lubna finds a pebble on the beach that quickly becomes her primary confidant and a source of comfort, though she also meets and grows close to a boy named Amir. When Lubna’s family finds out they’ll be leaving the camp, Amir is distraught, so Lubna bravely gives her pebble to him. Meddour’s story offers a child’s view of a global crisis and reminds kids that friendship and tenderness can flourish even in frightening situations.

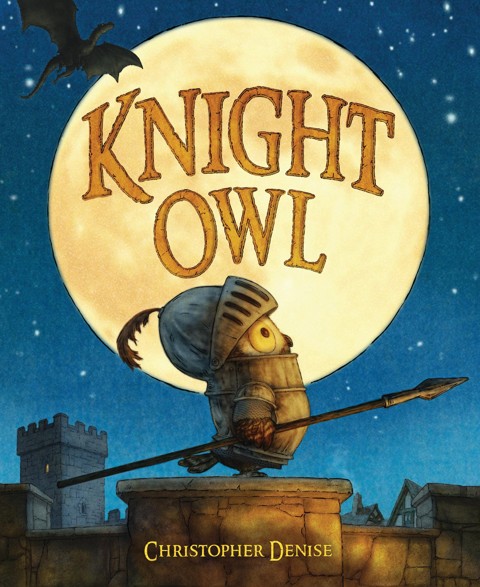

Knight Owl

written and illustrated by Christopher Denise

2022

Owl has only ever had one wish, which is to be a knight. He’s small but determined, so he applies to Knight School—and, shockingly, is accepted. Unlike his human classmates, he can’t maneuver his sword or shield, and he keeps falling asleep in class. But one night, while he’s serving on the Knight Night Watch, a dragon glides right up to his post on the castle wall. Owl is in danger of becoming a monster’s snack—until he finds something else for the dragon to eat. Our hero still might not be big enough to wield a weapon, but he manages to pull off something no one else could: gathering his fellow knights and the local dragons for pizza. By bringing the kingdom’s denizens together, Owl shows that there’s more than one way to care for one’s neighbors.

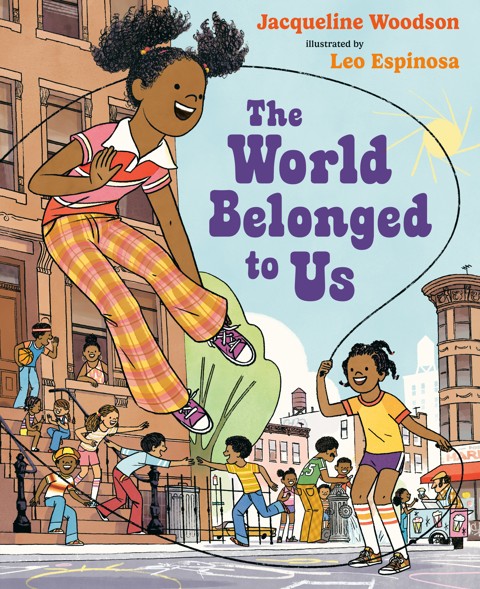

The World Belonged to Us

by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by Leo Espinosa

2022

Summer’s delights abound in Woodson’s tribute to “Brooklyn in the summer not so long ago,” when the end of school meant fun from dawn until dusk: jumping double Dutch, chasing down the ice-cream truck, building forts, exchanging stories. With help from Espinosa’s exuberant illustrations of city stoops and the subway, Woodson keenly captures the sense of community, friendship, and, most important, potential within the joyful chaos of urban life. In New York City, she writes, “it was easy to believe that anything was possible when a guy from our block was good enough to play for the Mets and a girl from our block sang on a big stage in Manhattan.” For now, though, these kids’ most urgent task is having fun.

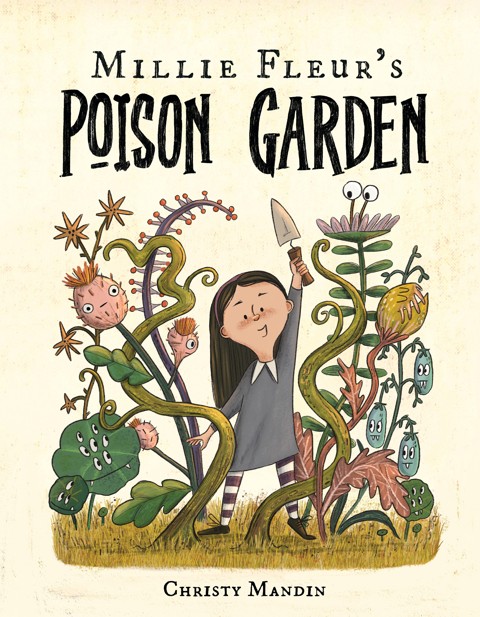

Millie Fleur’s Poison Garden

written and illustrated by Christy Mandin

2024

A witchy girl plants a fun, spooky garden at the edge of her new suburb, a cookie-cutter community that makes the standards of the most hidebound homeowners’ association look like a free-for-all. Mandin’s premise isn’t wholly original (the Addams family comes to mind), nor is her message that we are all better off embracing bits of eccentricity. But in that fertile soil, Millie Fleur grows a vegetal menagerie—toothy, monstrous stalks of fantastic species including grumpy gilliflower, fanged fairy moss, sneezing stickyweed, and swampy inkcap—all rendered in an earthy yet somehow kaleidoscopic palette. On the closing spread, some gardening tips involving creepy real-life plants might help a child’s dark fascination sprout into a lifelong habit.

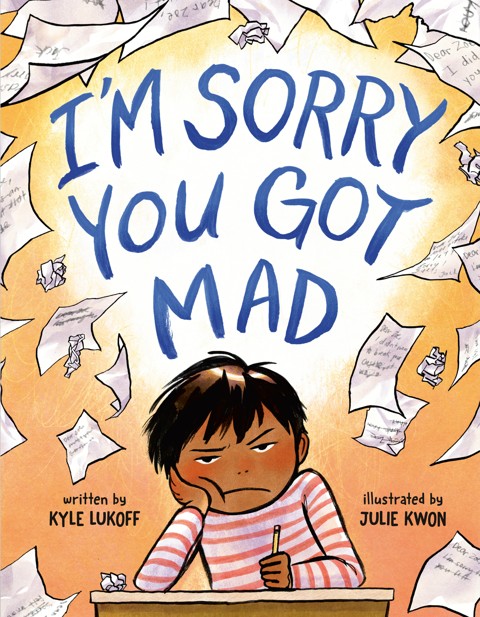

I’m Sorry You Got Mad

by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Julie Kwon

2024

Jack knocked over Zoe’s castle, but the best apology he can initially muster is a note scribbled with one word: “SORRY.” His teacher, Ms. Rice, is unimpressed; she asks him to try again. So we turn the page and see Jack’s next attempt: “SORRY ZOE.” Not good enough, Ms. Rice says. Fine. Jack writes, “DEAR ZOE, I’M SORRY YOU GOT SO MAD!!!” (In the margins, from Ms. Rice: “Please try again.”) Readers witness Jack gradually transform from a scribbling hothead into a compassionate and accountable playmate, as he learns a vital lesson applicable to children and grown-ups alike—how to truly make amends.

The post 65 Essential Children’s Books appeared first on The Atlantic.