This past July, I bought eggplants at the farmers’ market, intending to make my grandmother’s signature maqlubeh: the cinnamon-and-allspice-scented rice dish layered with fried eggplants and chicken, cooked in a pot, then flipped onto a serving platter, forming a golden dome. Before I had the chance to peel the eggplants, stripe by stripe, and drop them into hot oil, a WhatsApp message came in from my mother—a single, waving-hand emoji at an unusual hour. I knew immediately what it meant. My grandmother Teta Fatmeh, who had been ill for a while, had died. I experienced no tightness in my chest, no burning behind my eyes. Just a hollow stillness and sense of guilt.

Over the next few days, the eggplants sat in my crisper drawer, soft spots spreading across their skin like bruises. Every morning, I opened the drawer planning to make the maqlubeh. Every morning, I closed it again.

That week, I was supposed to be in Jaljulia—a small Palestinian town in Israel, near the West Bank—where my grandmother had lived her entire life. But our flights had been canceled amid rocket fire and regional escalation, fallout from Israel’s latest offensive in Gaza and its war with Iran. I found myself instead in my Pennsylvania kitchen, 5,000 miles away, doing math: one peaceful death compared with the thousands of violent deaths happening in Gaza; a woman who lived nearly nine decades compared with the children suffering from malnutrition and starvation who might not live nine years; a death witnessed by family compared with entire families erased, no one left to carry their names.

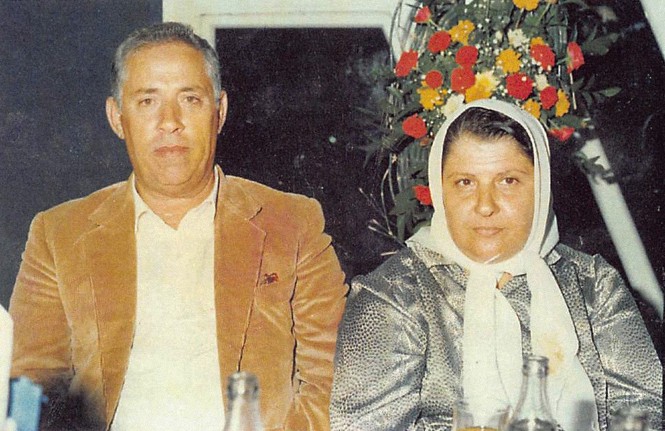

Teta Fatmeh, whose full name was Fatmeh Murrar, was born in Jaljulia in the late 1930s, before Israel existed—before the “green line,” the armistice boundary established following the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, split her family in half. When that line was drawn, many of her married sisters ended up just miles away on the other side—in what became the West Bank—and they didn’t embrace one another again for nearly two decades. Only after 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza, were they finally reunited. My grandmother was the last remaining sister. Now they are all gone.

Following the news of my grandmother’s death, I kept telling myself I would cook the eggplants tomorrow. But I couldn’t bring myself to start. Part of me didn’t want to accept that my grandmother was gone. Another part worried that the flavor of my favorite childhood dish would taste too much like comfort—and comfort, right now, feels like betrayal as so many Palestinians in Gaza go hungry.

This guilt isn’t new. I’ve carried it for years: What does it mean to be Palestinian when I’m spared the things that define life for so many other Palestinians—displacement, dispossession, siege?

Others may recognize this calculus. A woman mourning a miscarriage may minimize her pain when she hears of other women enduring the process of IVF because they are unable to conceive. Someone going through a breakup might tell themselves that their problems are nothing compared with a friend’s cancer diagnosis. A person feeling isolated during a pandemic might remain silent about their loneliness because others are losing their lives. Even the loss of a prized possession can seem illegitimate when—during wildfires, say—whole neighborhoods are reduced to ash. People measuring their grief against larger tragedies will frequently find it wanting. I shouldn’t feel this, one might think. Not when they have it worse.

A name exists for this reflex: disenfranchised grief. It is mourning that may feel unearned, inappropriate, underacknowledged, or too small for the world’s attention. Although the term itself is fairly new—coined by the bereavement scholar Kenneth J. Doka in the late 1980s—the idea is not. Emily Dickinson, writing in the 19th century, captured it in “I measure every Grief I meet,” which opens: “I measure every Grief I meet / With narrow, probing, eyes— / I wonder if It weighs like Mine— / Or has an Easier size.”

Grief never exists in a vacuum. For most Palestinians, since 1948 and what Arabs call the Nakba (“catastrophe,” in English)—when the creation of Israel led to massacres, the destruction or depopulation of more than 400 Palestinian villages, and the displacement of more than 700,000 people—our private sorrows have been refracted through the lens of the public pain we carry. Usually I, like many Palestinians, can carry both personal and collective losses. But in this moment, which finds me living in relative safety as so much of Gaza has been razed, the scale of atrocity has left no room. My grief from witnessing what has been done to my people is so vast, so relentless, that sadness over my grandmother’s death feels like something too indulgent. I am heartbroken, and I am ashamed of that heartbreak.

My shame is fed on a steady diet of videos and images that have been arriving without warning to my phone—ever since October 7, 2023, when Hamas carried out a brutal assault on Israel and Israel responded with a devastating bombardment of Gaza. Unlike the events of 1948, which my grandmother lived through but I inherited only in stories, the events taking place in Gaza now have been livestreamed into my kitchen via social media: a woman, eerily calm, cradling her dead niece, wrapped in a white shroud; a teen burned alive in his tent; a doctor learning that nine of her 10 children were killed in an air strike, after some of their bodies arrive at her hospital.

Each image recalibrates what feels worthy of my grief. But it’s not only Palestinians who carry this burden. Social media has democratized access to atrocity—anyone with a phone can witness Gaza’s devastation in real time. Some are beginning to ask what this unprecedented exposure will do to an entire generation. Will today’s young people grow up inclined to resist violence, or will they become numb from witnessing too much?

Even when grief seems illegitimate beside mass atrocity, it doesn’t disappear—it just finds a different outlet. After my grandmother’s death, mine kept getting rerouted by the sense that my sorrow was lavish when so many others weren’t allowed to mourn, when I had a lifetime of memories with my grandmother to look back on, while others died without the chance to start making theirs. My grief backed up until it came out as anger, when I finally removed the eggplants from their drawer.

I didn’t make the maqlubeh. I couldn’t bear the ceremony of that dish. So that night, we ate the eggplants simply fried, served with bread and tahini—what growing up we used to call “poor people’s dinner,” a meal my grandmother made on tired nights.

Yet even this make-do meal felt extravagant. So when my daughters, having left food on their plates, asked for dessert, I snapped: “There are kids in Gaza who would do anything for the food you didn’t finish.” It was a cliché. And I hated myself for saying it, for dragging war into their childhood, for stating something true in a way that felt cheap.

I wasn’t angry at them. I was angry that we live in a world with disparity so deep that basic comfort can feel like betrayal. I was angry that I couldn’t just say: I miss my grandmother. That I couldn’t just say: I wish she were still here—the woman who fed us as if nourishment were a language; who rolled maftool grain by grain, muttering about too many guests; who made bread by hand for msakhan and fried chicken next to maqlubeh every Friday, to gather her family. The woman who always asked me when I would finally have a boy (I have three girls) and later recanted, offering a date cookie and telling me that girls are the best, especially as you get old.

I longed for the grandmother whose kitchen taught me my first lessons about food and family, whose recipes fill the pages of my cookbooks, and whose stories echo through my writing—the one on whose Palestinian kitchen I built my American success.

As I look at the legacy my grandmother left behind, at the descendants—most of whom remain on our ancestral land—who became doctors and lawyers and writers, I find myself asking again: What right do I have to mourn someone who lived long enough to know her great-grandchildren when entire bloodlines are being buried? I also find myself asking what it means to grieve when grief itself must be justified—when mourning is a privilege and memory, like safety, that can feel so unevenly distributed.

I do not have the answer to those questions. So I try once more to turn to the language my grandmother taught me. I pick up eggplants at the market again, the late-season kind: a little larger and thicker-skinned. At home, I peel and slice them lengthwise the way Teta Fatmeh used to. I taste for bitterness, biting a morsel off like she always did. I salt and then fry. This time, I don’t hesitate to do the rest.

When I flip the maqlubeh into its golden dome, my 2-year-old claps because we are having “cake” for dinner. Tears smart my eyes. The rice is perfect, each grain separate, coated with ghee, and fragrant with spice. It tastes like childhood, like Fridays, like love. Yet with every bite, the contradiction sits heavy in my mouth: my grandmother gone in peace; children in Gaza dying without ever having known it.

I know that for Palestinians the act of cooking has never been separate from the act of surviving, of remembering. But that night at my table with family and close friends, I lived that truth the way my grandmother must have: the grandmother who never stopped cooking, never stopped gathering, never stopped setting the table—not during war, not when her family was split, not when she buried one of her daughters, lost too young to a medical mistake.

In a world that denies so many their humanity, feeding people, sharing stories, and creating space for joy and sorrow are their own acts of defiance: the way we Palestinians refuse to let cruelty strip us of our dignity. So I, too, will keep cooking and setting my own table—even as I struggle to comprehend why I am allowed this simple pleasure when so many others are not.

The post The Cruel Calculus of Palestinian Grief appeared first on The Atlantic.