In 2009, Apple coined a catchy slogan: “There’s an app for just about anything.” The original commercial is a time capsule from the early years—when the idea that smartphones could be used in every corner of life read more as a promise than a threat.

Now we have apps to help us stop using apps. The deterrents are creative. Some apps slow down how quickly we can open others; some block everything except calls and texts until we enter a specific password; some prompt us to reflect on a mantra or take deep, meditative breaths before scrolling on. One shows a little animated tree growing—a tree that dies if we open Instagram.

If an app for everything was prophecy, this is its dark fulfillment.

I tried these app-restricting apps for years in an attempt to kick my smartphone addiction. Looking at my phone all the time didn’t make me happy, but I couldn’t seem to stop. I would set a daily limit for my phone usage, and then ignore the notifications telling me I’d reached it. Whatever the barriers, I could always override them or change their settings. Looking at my phone was ultimately my decision; I had to make the right one a thousand times a day.

My friends and I were born in the aughts, the first children of the smartphone age. Recent years have seen a flood of advocacy and warnings about the effects smartphones have on kids, and a scramble for school policies to restrict their use. But they came too late for my generation. Gone are our childhood years, when schools and family could easily steer our choices. We’re more addicted than anyone, and there’s no one to take our phones away but us.

Most of us realize that our attention span is shot and our screen time is out of control—that the ability to do anything too often leaves us doing nothing at all. That’s why we create byzantine screen-restriction systems—and hate ourselves when we press “Ignore.”

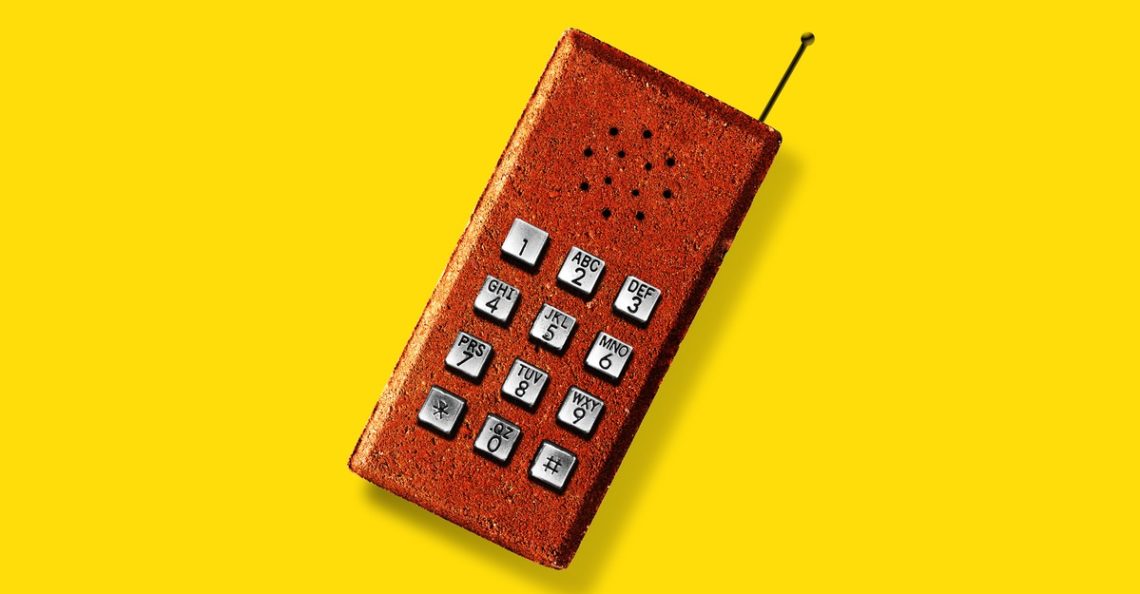

There is, of course, another solution: We could get rid of our smartphones altogether. But that’s quite a leap when you barely remember life without them.

A few years ago, a freshman at Stanford, Georgia Walker-Keleher, told a group chat full of friends that she’d be doing something “drastic.” She was trading her smartphone for a “dumbphone.”

“Did you get hacked?” one replied. Another quipped: “Text us in the green bubble if you need help.” One friend ran into Walker-Keleher on campus and sent a picture to the others confirming that she was alive and well.

My friends were similarly dumbfounded when, in July, I showed them my new Light Phone, one of a few modernized alternatives to retro flip phones. Mine has a camera, an MP3 player, and a maps tool. But the black-and-white, matte screen has no internet browsing, no social media, no news, and no email. In fact, it has no apps at all. When I asked the company’s co-founder Joe Hollier what separated a Light Phone from a smartphone, he said that the former would never have access to “anything infinite.” It is designed to have limits.

I’ve been learning those limits for a few months now. My first day was a logistical nightmare. The door to my office requires an app to unlock it; I couldn’t get inside, nor could I access Slack to ask for a hand. I just had to wait for someone else to come along. That evening, my roommates and I found a new apartment and realized that we needed to fill out an online application as soon as possible. Just a day before, I would have pulled out my iPhone—the magic box with all my bank accounts and pay stubs—and been done in five minutes. Instead, I made the hour-long commute home, where I powered up my laptop and thought about the convenience I had willingly given up.

The more we live on our phones, the more life requires us to do so; innovations such as QR codes and dual-factor authentication have made the world ever harder to navigate sans iPhone. Walking around without one feels like leaving your opposable thumbs at home.

Yet many of the apps we use every day are designed to keep us away from the outside world. Their core success metric is how many hours of your life they can take from you, and living in a constant state of digital gavage isn’t good for us. Chronic smartphone use has been linked to diminished cognitive capacity, social isolation, and poor mental health. The studies have been around for years, and most of us know their findings to be true at a gut level. Walker-Keleher described the feeling well: It’s not just disliking the smartphone; “it’s that I don’t like myself when I’m interacting with my phone. I feel like I don’t have control—like I’m in this constant battle to restrain myself.”

The app-limiting apps may help at the margins, but for most of us, they don’t take away that feeling.

My generation is often described as lacking a monoculture, because what we see on our screens is algorithmically siloed according to our interests and affiliations. But the screen is our monoculture: 98 percent of Gen Zers own a smartphone, and, for the youngest among us, our average screen time is a staggering eight hours a day. That’s equivalent to about 122 days a year—a third of our time on Earth. Ninety-five percent of 18-to-29-year-olds keep their phones with them “almost all the time during waking hours,” and 92 percent do so when sleeping.

You don’t have to be an extreme addict to have a problem. I’ve never been the “stay up ’til 5 a.m. watching TikTok in the dark” type. In fact, I gave up social media years ago, and I’m a notoriously hard-to-reach texter. For years, I had been meticulously culling my iPhone of its many allures and distractions. But I could always find something else to click. When I deleted Instagram, I became news obsessed. When I switched to reading physical newspapers and magazines, I still scrolled through photos I’d taken, compulsively tracked my finances online, and waded through Wikipedia. It was like a game of whack-a-mole with my dopamine receptors. I deleted everything compelling from my phone, but I still had an addictive relationship with the object itself; I’d pick it up only to realize I didn’t know what I was checking.

Jose Briones, who moved to rural Georgia after college for a software- engineering job, used to average 12 to 13 hours of screen time a day. Without the structured social world of campus life, he started “living online,” he told me. His friendships were filtered through Facebook and Instagram; he watched Netflix in every spare moment, including on his commute. “I don’t want that for my life,” he remembers realizing. “Something has to change.”

Shortly before the pandemic, Briones got himself a dumbphone, and he soon began posting online about it. His YouTube reviews of dumbphones now get thousands of views, and he moderates popular Reddit groups for “digital minimalists.” Perhaps there’s an irony in evangelizing the benefits of digital minimalism online, but young people make up the majority of his audience, and—at least for now—that is where they are. If you want to convert sinners, you can’t stay in the churchyard.

According to Michael Lloy, a tech analyst I spoke with at Mintel, a market-research company, 69 percent of 18-to-34-year-olds are actively trying to reduce their screen time (compared with 58 percent of adults overall), and many say—at least in theory—that they’d like to try a dumbphone. When Walker-Keleher and two classmates asked fellow students to volunteer to use dumbphones for a week as part of a study by the Stanford Social Media Lab, they had to close their interest form after receiving 250 responses in three days.

Despite all of this, Lloy confirmed what I already knew: Actual adoption of dumbphones is vanishingly rare. More than 100,000 Light Phones have been sold in the past decade; Apple has sold 23,000 times as many iPhones in that period. About 6 percent of the mobile-phone users his team surveyed have a dumbphone, Lloy told me, but the majority of those people barely or never use it—presumably because many have a smartphone too.

Many people who switch to a dumbphone describe a kind of conversion moment. Carter Hyde is 24 years old and getting her master’s degree in clinical psychology at Columbia. She told me that her middle-school years were defined by a “dark depression and anxiety from social media.” During her freshman year of high school, she was in a serious four-wheeler accident. She wasn’t injured, but her iPhone was shattered. When her parents took her to a Verizon store to replace it, she found herself asking: “Why am I spending so much of this precious life that I’ve been given on my phone?” She saw an LG Cosmos slide phone in a corner, complete with no app store—“It was, like, musty; there were cobwebs growing on it,” she joked—and knew immediately that she wanted it. Her mom laughed at her, and so did the Verizon guy. But she used that phone for the rest of high school. She told me that she slept better and felt better, and got better grades: “I was so much healthier and less tired all the time, less groggy.”

My own road to Damascus was a subway ride to Brooklyn. The train that day was full but not crowded: finance bros in suits, older people with little carts of groceries, a toddler in his mother’s lap. Everyone, even the toddler, was staring at the shiny rectangle in their hands. For that matter, so was I. This was not an unfamiliar sight, but for some reason, on that day, it struck me how dystopian our world would seem to a traveler from the very recent past.

My iPhone had often felt like a part of me—grafted onto my fingers or suspended at my hip. More viscerally than rationally, my body was finally rejecting the transplant. I suppose that’s what many conversion moments look like. The convert doesn’t learn any new information; what they already knew is simply made legible.

Switching phones didn’t change my life overnight. For one thing, I have a job now that requires looking at a laptop all day. For that reason alone, my daily screen time is probably higher than ever. But I have begun to notice little changes. I’m reading paperbacks on the subway—or sometimes just sitting with my thoughts. I’m sleeping better. I check my email over coffee in the morning, not over drinks with friends or in the bathroom at the bar.

For the digital-minimalism crowd, intentionality is more important than restriction. “When you do a research paper for school,” Briones explained, “you willingly decide, ‘I am going to be overwhelmed with information about this topic, and I want to do that.’” But the relationship we have with our phone doesn’t usually work that way: “There is a difference between willing cooperation—willing desire to have that information—and the unwilling reality of the algorithm.”

For this reason, Briones suggested, the use of dumbphones isn’t some retro trend like the readoption of record players and film cameras. “I don’t think it’s nostalgia,” he told me. “People, especially young people, are tired of being harmed without their consent.”

When Georgia Walker-Keleher finished her study at Stanford, many of the student volunteers switched back to their iPhones. Carter Hyde’s parents encouraged her to get a smartphone again when she moved to L.A. for college. She was going to be in a new place and living on her own. She needed to be able to call an Uber in an emergency and check her bank balance while out with friends. But she was worried. “My biggest fear,” she remembers, was “reverting completely back to my old ways.”

Her experience in high school had inoculated her for a while. For a few years she managed to stay intentional about her use, with the help of screen-time apps and limits. But more and more, she found her time spent on the phone creeping up again. When we spoke, it had been eight years since the accident, and she confessed that she was “back to chronically scrolling.”

She told me she “would love nothing more” than to go back to using a dumbphone. For now, though, she was calling me on her iPhone. “I just know that, you know, there’s so much of my life that’s on the phone.”

The post There Is Life After the iPhone appeared first on The Atlantic.