If you’re involved with an active addict or substance abuser, you will be lied to and made a chump of: It’s axiomatic. As when Elizabeth Gilbert’s friend and eventual lover, Rayya Elias, assures Gilbert and the rest of their circle that the little bottles of Angostura bitters she keeps stowed in her purse and habitually chugs straight from the bottle while claiming to be sober—indeed, while attending AA meetings and publishing a well-received memoir about her victory over substance addiction—don’t contain alcohol. (The alcohol level is 44.7 percent.)

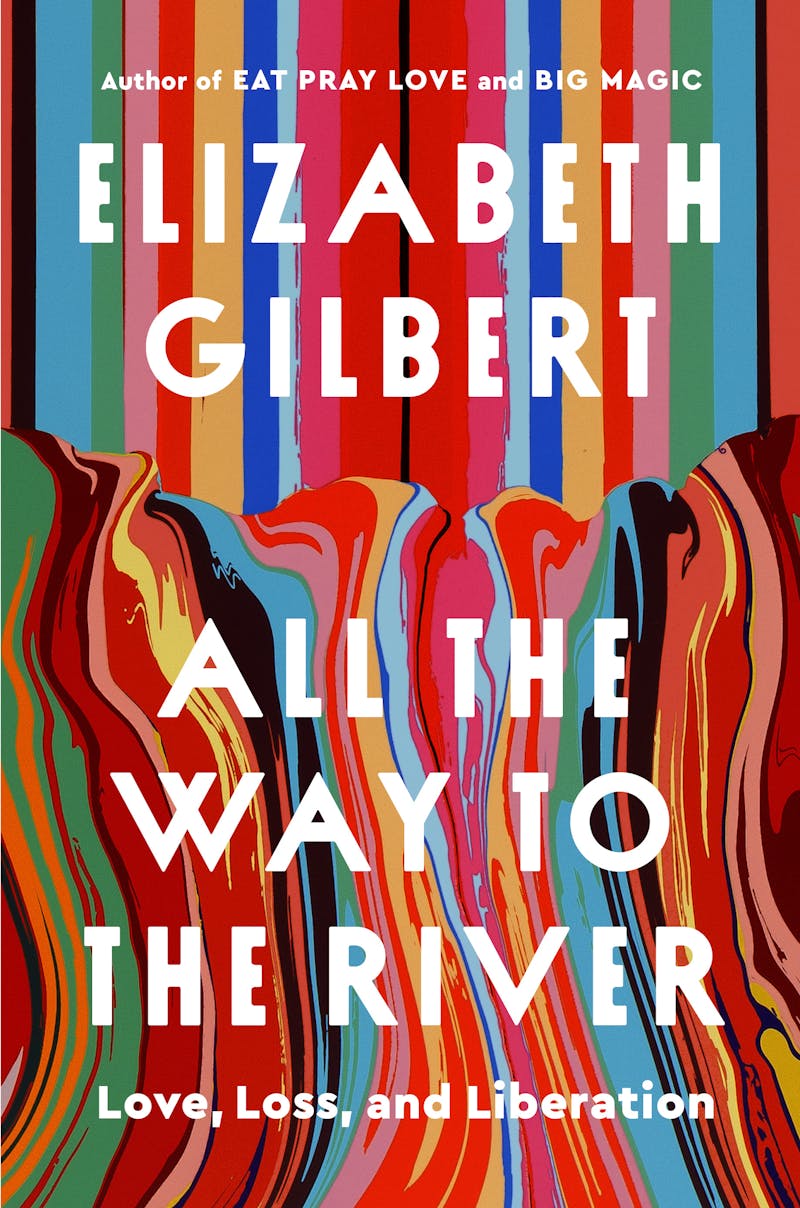

Over the years, as Gilbert relates in All the Way to the River: Love, Loss, and Liberation, she observed Rayya—who’d also had hepatitis C, so shouldn’t have been drinking at all—telling people, on multiple occasions, and with totally convincing sincerity, that she either hadn’t read the label, or the alcohol in bitters is actually different than regular alcohol, or her doctor had recommended drinking bitters to ease her chronic stomach pain. Like all addicts, she’s emotionally manipulative. Given the global epidemic of substance issues and addictions, the cognitive dissonance of someone you love flat out lying to your dumb, credulous face will ring uncomfortably true for many of us.

About these dilemmas and her own complicity in this one—she’d been the one who insisted Rayya write the addiction memoir, supporting her while she did—Gilbert can be mordantly, self-indictingly funny. On the one hand, Rayya was “the single most honest person I had ever met”; on the other, she was lying on a daily basis. This includes later informing Gilbert, with the same convincing sincerity, that a doctor had prescribed medical grade cocaine to her—“so she may not have been a reliable narrator on such matters.”

A queer Syrian-born and Detroit-raised ex-junkie, ex-dealer, and ex-felon, Rayya had become a successful hairdresser after getting clean—few had ever so adeptly tamed Gilbert’s frizzy mess of hair. They became friends, then inseparable friends, then traveling companions, with Rayya joining Gilbert on book tours and red carpets—they were almost a couple, everywhere but the bedroom. Then in 2016, in her mid-fifties and weakened by years of addiction (drinking on top of hep C may have contributed), Rayya was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic and liver cancer and given six months to live. Following which, though ostensibly happily married to the handsome older Brazilian man she’d met at the end of her 2006 bestseller, Eat Pray Love, Gilbert declared her love for Rayya—whom at that point she’d never so much as kissed—and left her husband.

The two become an official couple and have some good months, with Gilbert, grandly electrified by the intensity of the situation, dropping everything and pledging to stay with Rayya to the end (“all the way to the river”). The plan is to selflessly escort her lover to her imminent death, which turns out to be less imminent than anyone had thought: Rayya hangs on for 20 increasingly disastrous and destructive months. As the cancer progresses, she spins out of control, shooting street drugs into her neck when the prescribed painkillers stop working, spending a fortune of Gilbert’s money on luxury items—a Range Rover, a Rolex, a rented penthouse—while lapsing into venomous frenzies, so abusive she’s even kicked out of hospice. By now, Rayya is imbibing deadly combinations of booze and drugs, the two are fighting every day, are up all night (coke isn’t great for the sleep cycle), and descending into mutual psychosis. On the rare occasions that Gilbert manages to fall asleep, Rayya wakes her up to harangue her, to the point that Gilbert starts plotting to literally murder her beloved to end the mutual nightmare and finally get some rest.

The harrowing quality of this descent is dark catnip for the reader: The more gothic things get, the more gripping the story becomes. At the same time, Gilbert wants us to understand that, despite everything, Rayya was and is still the love of her life, her “beautiful story.” The job is to convince us of Rayya’s magnetism and specialness by selling us on her contradictory charms, showing us her talents as “an unfailingly honest master manipulator,” “a social magician” with extraordinary instincts about people, and ultimately making us fall in love a little with her, too.

It turns out Rayya’s charisma even extends into the afterlife—five years later, Gilbert is still being haunted, not unpleasantly, by Rayya’s foul-mouthed antic spirit, which also shows up periodically to chat and offer social guidance. “Tell this bitch she can fuck right off, said Rayya, from inside my head,” about an intrusive stranger at a party. “Tell this idiot she can jump directly up my dead fucking ass,” Rayya insists when Gilbert fails to comply. “Rayya is more vivid in death than most people are in life!” Gilbert quips to friends.

Whether or not communing with the dead is your thing, there’s an enduring strain of spiritual eccentricity and wandering in American literature, from the transcendentalists to Melville to the Beats, and so on, that Gilbert is tapping into. I’d propose adding her name to the notables.

Though the Rayya saga takes up a good chunk of the book, it’s actually more of a frame story. Indeed, if you’ve read Gilbert’s massive bestseller Eat Pray Love, you’ll recognize that the setup here is much the same: Relationships end (in EPL, her marriage and a love affair), and a journey of self-discovery ensues. EPL took Gilbert to far-flung locales and made her the patron saint of women yearning to break out of their lives; this one takes her from another marriage and another love affair into “the rooms”—12-step meetings and recovery—where legions of fellow sufferers have come and gone.

Her big realization is that Rayya wasn’t the only addict. She, Elizabeth herself, is a sex and love junkie. People are her substance—“I needed Rayya at a level that was far beyond healthy. I came to believe, quite literally, that I could not live without Rayya.” She smokes lovers like crack, then crashes and wants to die, but without an influx of emotional chaos, she’d soon go into withdrawal.

Meaning perhaps she was even responsible for Rayya’s relapse (taking a fearless moral inventory is the crucial Step Four)—after all, she’d used and manipulated her by declaring her love when Rayya, having just been told she was dying, was at her most vulnerable. “Driven mad by fear and longing, I tried to drain all the love from Rayya into me before she died—as though through some crazy emotional blood transfusion. In so doing, I turned into a vampire, which is what all active addicts eventually become.”

Fearless moral inventories are all to the good, even if, conceptually speaking, this is something of a high-wire act: simultaneously debunking the course of events with Rayya as a symptom of her own addiction while celebrating Rayya as her life’s great love; insisting that Rayya was a magical person but also that sex/love addicts assign magical qualities to people (“pedestaling”). Even if Gilbert hadn’t questioned Rayya’s lies because to her Rayya was a godlike figure, and because she was addicted to Rayya, we’ve seen just how convincingly Rayya lied to all the non–sex/love addicts in her orbit, too.

The question is whether Gilbert can pull it off. I’d say mostly yes, because she’s such a likable writer, matched by few in her sprezzatura on the page. Coherence isn’t entirely required when her goofy, self-deprecating charm is so winning—at any rate it wins me. Gilbert is a world-class specialist at reporting on her emotional struggles in ways that resonate with a collectivity of baffled, mostly female co-strugglers—every woman saddled with aspirations and emotions badly suited for happiness, perpetually mismatched with the possibilities the world actually contains.

Recovery—“being in the rooms”—meant disengaging from not just sex and love, or at least her usual high-intensity patterns of acquiring them, but eventually also alcohol and drugs (she was big on hallucinogens), which wasn’t strictly required, but her new life is going to be about rules and boundaries. Gilbert’s fans will probably recall that she arrived at precisely the same insights in Eat Pray Love, announcing that “addiction is the hallmark of every infatuation-based love story,” and that she herself was such an addict, with the bad habit of throwing herself at people. Until she realized, as in the current book, that prayer and spirituality are salves, and celibacy—at least in the year and a half prior to meeting the charming Brazilian guy—is a necessary step.

Who’s in a position to fault Gilbert for learning and forgetting the same life lessons over and over? Not me. Will the new celibacy pledge last? I wouldn’t bet the farm on it. Gilbert is too helplessly alive to other people. Everyone she encounters seems to have figured out something she thinks she hasn’t, hence their allure: She’s not just addicted to love but to answers. If she was criticized for turning Eastern mysticism into a spiritual shopping mall, it wasn’t Indian yogis and Indonesian medicine men alone whose teachings she guzzled; every random stranger seemed to have life wisdom to impart. Rayya couldn’t be merely a relapsed junkie; she was a spiritual guide sent to jolt Gilbert into the next level of self-awareness.

This unsnobby receptiveness to people in all their motley weirdness may be a festering symptom of something, but it’s also quite a wonderful talent.

It’s common among intellectuals and secular types to sneer at 12-step clichés—the term “Oprah-ish” in not an approbation in these circles. Please be assured that I’m secular to the core, but it also seems obvious to me that idioms of addiction and recovery are, practically speaking, the only means our culture has to express, and attempt to relieve, spiritual suffering.

Being “in the rooms” is a way to speak about spiritual anguish in uncommercialized peer-to-peer settings, rather than in glitzy, dollar-driven megachurches, and unmediated by the hierarchies of organized religion. And how many versions of such pain does an insatiable consumer society cultivate in the psyches and appetites of its populaces? Even “normal” addictions—fast food, online shopping, scrolling—are debilitating and ruinous, but frantically craving humans (“disordered-disoriented” is the attachment style of Gilbert’s romantic history, she says) are a functionally useful, which is to say lucrative, character type in this social order. That’s my read, not Gilbert’s—she’s not particularly interested in social analysis, defaulting toward thinking that human needs and behaviors are timeless.

Of course, some of the unease about Gilbert’s own work is that it’s crack for advice addicts, which has also made her too commercially successful—some 25 million combined book sales worldwide—for intellectuals to have to take her seriously. (I got some significant eye-rolling from friends when I mentioned I was writing about Gilbert’s new book.) Additionally, her torments are chick torments, not important David Foster Wallace–style torments. Even when depressed, she’s more suburban than cool; even her worst breakups lack the MFA cred of a Sarah Manguso or a Leslie Jamison. As Gilbert herself knows and rues, describing her beige-hued outfit, the day she met the black leather–clad Rayya, as making her look like a Banana Republic salesclerk.

And yet, and yet. Throughout the new book, I kept being reminded, unaccountably, of the poet-philosopher Emerson, and trying out sentences in my head like “Is Elizabeth Gilbert the Ralph Waldo Emerson of our time?” “Is Elizabeth Gilbert Chick Lit’s Transcendentalist-in-Chief?” I have no idea if Gilbert has actually read Emerson, though the titles of her early books Stern Men (a novel) and The Last American Man do echo his famous 1850 title Representative Men. But All the Way to the River shares quite a lot of Emerson’s spiritual questions and conclusions, particularly those of his 1841 essay “The Over-Soul.”

The comparison may be less of a reach than it sounds, as there’s a shadow intellectual lineage, given Emerson’s handprint—and that of the transcendentalists generally—on the Alcoholics Anonymous Big Book, which Gilbert, long a sponge for spiritual wisdom, has lately immersed herself in and quotes multiple times here. The Big Book’s emphasis on an individual concept of the divine (“God as we have understood him”) and spiritual awakening through experience rather than scripture or churches, is decidedly Emersonian. Emerson’s godson, the philosopher-psychologist William James, was also a major influence on AA cofounder Bill Wilson in the writing of the Big Book.

A Boston clergyman before parting ways with the church over his religious unorthodoxies, Emerson, like Gilbert, sojourned abroad, also spending several months in Italy. On his return, he hit the road, doing hundreds of talks across the country. Like Gilbert, he drew on Eastern mysticism, especially the Bhagavad Gita. Both depart from traditional Christianity to knit together an eclectic, novel spirituality—Gilbert’s latest update offers a mélange of 12-step insights, some occult and soul travel, along with neuroscience and trauma theory. Both locate a personal God that resides within and can be conferred with directly. Gilbert’s even answers back, though when she inquires whether she should start dating someone new after Rayya, frustratingly He keeps responding “Lol no.”

Breezy tone notwithstanding, Gilbert does often sound quite similar to Emerson: “What if Earth is nothing but a school for souls?” asks Gilbert. Emerson puts it more long-windedly in “The Over-Soul”: “The soul gives itself, alone, original, and pure, to the Lonely, Original, and Pure, who, on that condition, gladly inhabits, leads, and speaks through it… Behold, it saith, I am born into the great, the universal mind.”

Gilbert’s aptitude for speaking from what Emerson calls “the common heart” often does have a ring of the nineteenth-century pulpit:

For who among us has never gotten lost, much to our own embarrassment? Who has not ended up in scenarios that are frightening, alienating, shameful, and spirit-crushing. Who has not kept secrets, or been betrayed, or tried to control the behavior of others? Who has not longed for escape from suffering?

Emerson suffered losses (his first wife, his son) that left him shot through with grief. William James had what used to be called a nervous breakdown, followed by a period of travel in Europe to recuperate—as with Gilbert, emotional pain sent them on overseas journeys and spiritual investigations. The varieties of soul sickness come differently labeled in our time—we use idioms of addiction and compulsion rather than nervous collapse; our journeys are generally to the pharmacist’s counter instead of curative tours of Europe.

If Gilbert’s depressions and quests prompt more snark about self-help tourism and privilege than do the comparably privileged Emerson’s travels and inquiries about the soul, of course he spoke with loftier high seriousness. Gilbert’s pop feminine style is unlofty to a fault. Perhaps it’s why her invite to the table of canonical American questers and seekers seems to have been lost in the mail.

Does a writer have to sound ponderous to be taken seriously? Is Gilbert’s endless need and enormous ability for reeling people in then smothering them with likability and charm a detriment? Given her own self-analysis, I suppose it’s legitimate to ask whether her writerly superpowers are also the symptomology of a love addict? To the extent that authorial style is always a negotiation between craft and neurosis, of course they are.

But then there’s Gilbert’s ingenuous ability to yank you, out of the blue, to surprising uncharted places, as when pondering the Rayya relationship: “I was forced to ask myself what, in fact, I believed to be true about the universe: Is it friendly, or is it malicious?” Is life useless suffering, or is there a point? It sounds like a simple question, simple enough to spend the entirety of your existence attempting to answer it.

The post The Spiritual Appeal of Elizabeth Gilbert appeared first on New Republic.