AP Photo/Jean-Marc Bouju

- Jane Goodall, a pioneering primatologist who befriended chimpanzees, is dead at 91.

- She discovered that chimpanzees make and use tools, engage in war, and have personalities.

- Later in life, Goodall pivoted to conservation and led a crusade to protect wild places.

Jane Goodall, the pioneering chimpanzee researcher who changed our understanding of what it means to be human, died while on tour in California at 91 years old. The Jane Goodall Institute posted a statement October 1 saying she died “in her sleep” and of natural causes.

Goodall dedicated her life to environmental conservation and the study of animals in the field.

A secretary from a middle-class British family who couldn’t afford college, Goodall dreamed of living in Africa among the creatures of the forest long before she did so.

“At the time, I wanted to do things which men did and women didn’t,” she told National Geographic in the 2017 documentary “Jane.” “You know, going to Africa, living with animals.”

Goodall first visited Kenya in 1957, and met archaeologist Louis Leakey there. He hired her to observe chimps in the wild, and that initial journey into the forest — for a researcher with no formal training but ample patience and keen observational skills — was the beginning of Goodall’s lifelong investigation into what makes us human. The trip also fostered her love of nature; Goodall spent the later part of her life as an international ambassador for wildlife conservation.

Goodall discovered that humans aren’t the only creatures who use tools

AP Photo

Goodall recruited her mother to accompany her on her first research trip to the Gombe Stream Game Reserve (now Gombe National Park) in 1960, since women at the time were not typically allowed to perform such research missions solo.

In Gombe, she spent nearly half a year simply observing chimpanzees from afar, climbing into trees wearing black Converse All Stars to watch them. After about five months of observation, Goodall gained the primates’ acceptance, which allowed her to watch them groom and report on their movements and behaviors like no other researcher had before.

She discovered that like us, chimps make their own tools. This realization came when she saw a chimpanzee (whom she’d named “David Greybeard”) use a twig to fish termites out of a nest. The chimp stripped the twig of its leaves, then dipped it into the termite mound.

Her report about that finding, called “Tool-using and aimed throwing in a community of free-living chimpanzees,” was published in the journal Nature in 1964. It was revolutionary, since scientists thought at the time that humans were the only animals capable of such innovation.

“It had long been thought that we were the only creatures on Earth that used and made tools,” Goodall said to National Geographic. “And here was David Greybeard using a tool.”

After that discovery, Goodall went on to attend Cambridge. She received her PhD in animal behavior (ethology) in 1965, without ever obtaining a bachelor’s degree. Some scientists scoffed at the way she named the chimpanzees she met while conducting her research, arguing that animals should not get human-like monikers.

Goodall didn’t agree.

“We find animals doing things that we, in our arrogance, used to think was just human,” she told National Geographic on her 80th birthday.

Goodall also discovered that chimpanzees conduct warfare and sometimes engage in cannibalism and other dark behaviors like infant killing.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Goodall wanted to replicate the best of what she saw in chimpanzee mothers

In order to pursue her research work, Goodall had to overcome some inappropriate advances in the form of unrequited love letters from her boss, Leakey.

“I was in a very difficult position, because on the one hand I hugely admired him,” she said of Leakey in an interview with the Guardian in 2010. “He knew so much. He also had my whole future in his hands. On the other hand, I thought: ‘No thanks.'”

Goodall faced unfair treatment from other sources as well. The National Geographic Society, which funded her research, once insisted that Goodall be photographed washing her hair in a stream. Other stories about her discoveries often focused more on her looks than the science.

“The media produced some rather sensational articles, emphasizing my blond hair and referring to my legs,” Goodall wrote in TIME in 2018. “Some scientists discredited my observations because of this — but that did not bother me so long as I got the funding to return to Gombe and continue my work. I had never wanted to be a scientist anyway, as women didn’t have such careers in those days. I just wanted to be a naturalist. If my legs helped me get publicity for the chimps, that was useful.”

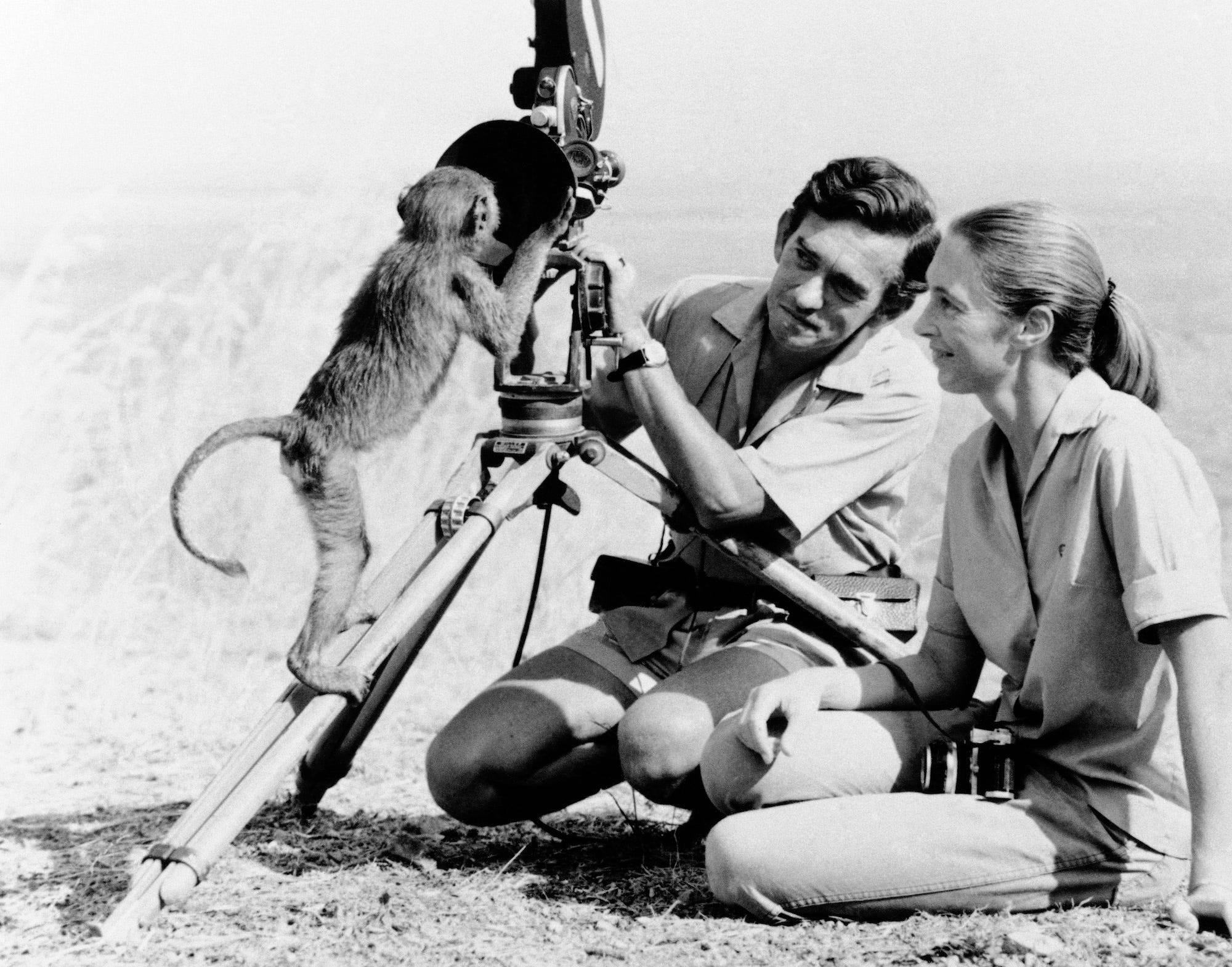

Goodall said she never thought she would get married, but she fell in love with wildlife photographer Hugo Van Lawick when he took pictures of her for National Geographic. The two married in 1964 and had a son named Hugo, whom Goodall affectionately called “Grub.”

Goodall credits chimpanzees with helping her become a better mother. Her observations in the forest suggested that chimp mothers who are affectionate and supportive of their youngsters engender more self-confidence in their offspring, so she strove to do the same.

After 10 years of marriage, Goodall and Van Lawick divorced in 1974. The next year she married Derek Bryceson, director of Tanzania’s national parks. The couple stayed together until Bryceson died of cancer in 1980.

AP Photo/MTI, Barnabas Honeczy

Goodall became a leading voice for wildlife conservation

In 1977, driven by the realization that chimpanzee habitats were being extinguished, Goodall started the nonprofit Jane Goodall Institute. She became a globally recognized face of the conservation movement.

In 1991, Goodall incorporated the “Roots & Shoots” youth service program into the work of her organization in order to inspire young people to get involved in caring for the planet’s natural habitats.

Her advocacy for animals and the environment extended to the halls of government, too. In the 1980s, Goodall lobbied the US National Institutes of Health to improve conditions for chimpanzees in lab experiments. Thirty-five years later, in 2015, the last federally owned chimps retired from life as lab-research subjects.

“I have long advocated for the end of invasive research on chimpanzees,” Goodall said at the time. “This decision was made after a special task force investigated all research protocols and found none of the research was beneficial to human health.”

Goodall was named a UN Messenger of Peace in 2002 and a Dame of the British Empire (the equivalent to knighthood) in 2004. She was inducted into the French Legion of Honor in 2006.

Gustavo Caballero/Getty Images

Goodall always acknowledged that there are critical differences between humans and chimpanzees, despite our relatively similar brains. Language, she said, is the greatest divider — the thing that allows people abstract thought and an ability to fast-forward and rewind time.

“With language we can ask, as can no other living being, those questions about who we are and why we are here,” she told National Geographic in “Jane.” “And this highly developed intellect means, surely, that we have a responsibility towards the other life forms of our planet whose continued existence is threatened by the thoughtless behavior of our own human species.”

Read the original article on Business Insider

The post Jane Goodall, chimpanzee researcher and conservationist, is dead at 91 appeared first on Business Insider.