In its first eight months so far, the Trump administration has fired or otherwise relieved some 15 senior military officers, most of whom were high-ranking three- and four-stars in the force. The first three months alone saw the abrupt removal of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the chief of naval operations, commandant of the Coast Guard, vice chief of staff of the Air Force, director of the National Security Agency, and the seniormost lawyers in the Army, Navy, and Air Force. After what seemed like a pause, the forced removals renewed with the firings of the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency and two admirals, the unexpected early retirement of the Air Force chief of staff, and the out-of-cycle reassignment of the superintendent of the Naval Academy. In addition, the administration made numerous unexpected personnel appointments that effectively ended the careers of some of the most celebrated military leaders. Beyond all of this, reportedly President Donald Trump plans to personally interview all prospective four-star nominees across the services.

The administration couched the removals as consistent with the presidential prerogative to choose its military advisors. Previous presidents did have this power, and every administration has fired a few military leaders, made some surprise appointments, or exercised close presidential scrutiny of the selection of personnel to a few of the seniormost positions. None has relieved so many, nor shaped the appointments so forcefully, this early in the president’s tenure. No previous administration exercised its power in this dramatic fashion for fear that doing so would effectively treat the senior officer corps as akin to partisan political appointees whose professional ethos is to come and go with changes of administration, rather than career public servants whose professional ethos is to serve regardless of changes in political leadership.

These personnel moves have been poorly explained to both the public and the individuals relieved, but one thing was made clear: None of the officers had committed a grave fault—insubordination or dereliction—that would have made their removal obvious and noncontroversial. To relieve so many senior officers so soon in an administration amounted to a dramatic break with past precedent, raising two obvious questions: What are historical norms and best practices around relieving senior military leaders, and how should senior officers still serving function in the present moment?

The power to determine who will lead the military is an important lever of civilian control. The framers of the Constitution saw it as vital and took pains to share that power between the executive and legislative branches. Civil-military relations theory likewise underscores the role of the rewards and punishments inherent in the up-or-out system of promotions. When presidents have expressed an extreme reluctance to exercise control for fear of the political clout of senior military officers—think President Bill Clinton during his first months in office—the resulting diminished expectation of punishment can produce an unhealthy imbalance between military and proper civilian control, producing needless friction that corrodes trust within civil-military relations.

Over the past two decades, presidents and their secretaries of defense have removed leaders—or forced their resignations—for a variety of reasons. Among other cases, for example, the George W. Bush administration removed Adm. William “Fox” Fallon from U.S. Central Command for publicly disagreeing on Iran policy and Air Force chief of staff Gen. T. Michael Moseley for systemic deficiencies in the handling of nuclear weapons and other concerns. The Obama administration removed Gen. David McKiernan when it thought another general would be better aligned with its Afghanistan policy and then removed McKiernan’s replacement, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, for allowing a command climate that was politicized against the president to take root. In these and the handful of other such personnel actions undertaken on their watch, the Bush and Obama administrations took pains to explain why the action was necessary.

When the Trump administration announced the departures of the military officers, such clear and compelling explanations were absent. The on-the-record talking points were vague and the anonymous backgrounders raised more questions than they answered. For instance, the Trump team argued that most of the firings that have occurred to date were akin to the “McKiernan” category: wanting to go in a different direction. But the closer the analogy is examined, the less well it seems to apply. President Barack Obama and his team spent five months in frustrating exchanges that convinced them McKiernan would not be a good fit for the new direction they wanted to go in Afghanistan. As recounted in his memoir, Duty, former Defense Secretary Robert Gates wrote that McKiernan’s background as an armor officer in conventional assignments made him ill-suited for the asymmetric warfare in Afghanistan, and they further locked horns for months over the command structure in Afghanistan and problem of civilian casualties. Officials trying to explain the firings in 2025 could point to no similar good-faith effort to “make it work.”

Defending the Trump administration’s approach, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth asserted that Obama removed hundreds of military officials during his tenure. However, this is misleading. Over his eight-year tenure, Obama did remove some high-level officers, as noted above. But to get the count to “hundreds,” one has to add up all the officers of much lesser rank who were routinely relieved by their higher-level military commanders for a loss of confidence in their abilities or well-documented transgressions. That is apples-to-oranges different from the high-profile, civilian-directed removals of flag and general officers addressed here.

In the absence of any compelling justifications, many observers concluded they were relieved for being the “wrong” gender or “wrong” race, noting that seven of the 15 officers removed to date were women and three were racial minorities. This disproportionate tally has not been lost on people of color and on women in general who have come forward to serve their country as part of an all-volunteer force.

Regardless of the circumstances of why, there is a common template for how. It is customary for the senior officer to learn in private and in person and have it explained before it is announced; the officer is given the option of retiring so as to keep the earned retirement benefits; and the officer usually leaves quietly so as to reinforce the norm of civilian control. The exceptions—for instance, when Maj. Gen. John Singlaub continued to criticize President Jimmy Carter even after being relieved of command in South Korea or when Gen. James Mattis was informed about his early relief by a low-level public affairs officer rather than his chain of command—are held up as examples of what not to do.

When civilians want to make a change in senior military leadership for a change of policy direction, as opposed to some form of dereliction, they often will look for ways to reassign the officer to a position that better aligns with their abilities—even if it means “kicking them upstairs” with a promotion, as was done with Gen. William Westmoreland during the Vietnam War and Gen. George Casey during the Iraq War—both of whom later became chief of staff of the Army after their wartime commands.

The Trump 2.0 actions have followed some of these norms. All of the officers have left quietly and, so far as we can tell, have since refrained from commenting on the circumstances surrounding their removal—a stark contrast to the stormy departures of the political appointees serving in Hegseth’s inner circle. To our knowledge, so far, they were all given the opportunity to retire with benefits, although some were forced to vacate their military housing with little notice—a move without precedent for those fired without cause.

On the other hand, none of the Trump-era removals was well-explained, and only one case so far—the relief of the Naval Academy superintendent—followed the pattern of moving the officer to a lateral position so as to allow a capable officer to continue to serve. Moreover, few if any of the personnel actions appeared to be done in person with the customary private courtesies and were done so abruptly that some learned about their relief from third parties while traveling.

The firings produced little to no public outcry, but some critics have asked, what will it take for Trump and Hegseth to return to the norms previous administrations abided by? This is a valid question, but it may not be useful from the standpoint of helping current senior military leaders who must honor their oath to uphold civilian control and the military’s norm of nonpartisanship regardless of what civilians do. It is clear that neither the president nor the secretary has evinced any doubt about the wisdom of shaping the military in this way. Moreover, while a marked departure from established practice, what they are doing is legal and consistent with the constitutional principle of civilian control. It seems obvious that the administration will continue in its approach unless or until Congress exerts its constitutional powers to constrain executive discretion.

Thus, the more pressing question for the health of the military profession and of democratic civil-military relations is how senior military leaders can best adjust to the new reality. A bedrock principle of military doctrine is not to “fight against the terrain”—meaning they should accept mountains and rivers and other constraints as they are, adjusting to them rather than wishing them away. In the present moment, the norm-busting style of Trump 2.0 is the “new terrain” and is unlikely to change anytime soon.

The fact remains, therefore, that while every administration has fired some military leaders, none has relieved so many, so early in their tenure, and in this dramatic fashion. As a result, this new approach to civilian control has generated considerable confusion and consternation among senior military ranks. Senior military officers are inevitably asking what is the right response and may be considering one of the following four problematic options.

First, many officers may simply decide to quietly quit. “Quiet quitting” in these circumstances is opting for retirement rather than staying for another tour of service. In an all-volunteer force, that is always an option, and based on anecdotal evidence, this option seems to be top of mind for many officers. This course is not a political act, unlike resignation in protest discussed below, and allows officers with professionally grounded objections to leave without posing a direct challenge to civilian control. If done in sufficient numbers, however, it could pose a challenge to warfighting readiness and could play havoc with the painstaking efforts all of the services engage in to grow their best junior officers into generals and admirals. It also is at odds with the “stay at your post” tradition that professional militaries adhere to in troubled times and sends a discomforting message to their subordinates in the process. It is never a good time to bleed talent, but losing the best of the services precisely when the country is facing the most complex security environment of the post-Cold War era would seem the worst time.

Second, in response to a policy disagreement or because they think the military is being used for immoral or unethical purposes, senior officers might choose what civil-military relations scholars have long viewed as taboo: resigning in protest. Unlike quiet early retirements, resignation in protest by a general or flag officer in response to a “lawful but awful” order is a public political act that undermines civilian control and politicizes the military. While this remains an option senior officers might consider in the face of an onslaught of illegal orders, it is also the least likely of the four to occur. There is no tradition of generals resigning in protest in the modern era. In practice, senior military leaders have deemed such a public political act to be at odds with military professionalism and basic democratic ideals. It is possible that continually treating the military as if it were a partisan political actor will eventually drive its members to behave as partisan political actors; in that case, resignations in protest will start to happen. If so, we will be in a different and ominous new era in American civil-military relations.

A third possible reaction could be for officers to pick a policy fight with civilian superiors and conduct it in public through leaks and other brazen acts precisely to guarantee that they will be fired. The officer would maintain some veneer of professionalism by not taking the provocative step of resigning in protest, but it is nonetheless a political act that would undermine the military’s credibility as a nonpartisan actor. To be clear: Providing advice that a military leader knows is inconsistent with a stated or implied preference of a civilian leader is not picking a fight, as we explain further below. In fact, giving honest advice to senior decision-makers is the military leader’s duty, regardless of the personal consequences. Rather, the problematic behavior contemplated here would go well beyond providing candid advice and cross the line into political machinations designed to thwart the administration. While this scenario is also unlikely (because it suggests a level of political machination within the military that simply is not there), some political opponents of the administration have suggested that senior military leaders should function as a check on perceived excesses of presidential power. We do not expect the military to act in this way—and certainly do not advocate that it does so—because the military does not see itself as part of a political resistance or inhabiting a role that belongs to the civilian branches of government. The best military leaders understand that such forms of politicization would undermine civilian control and worsen civil-military relations.

The final possible ill-advised response might be the most seductive: self-preservation that crosses the line into careerism. This would involve senior officers acting in a manner where their overarching consideration is to avoid being fired at all costs. In practice, this means failing to offer their true military advice behind closed doors, lest it be met with disapproval or dismissal. It also might entail failing to provide important and accurate but unwelcome information. It also means going well beyond the normal trust-building that is essential in any hierarchical relationship and crossing the line into politicized behavior designed to curry favor with civilian political leaders, such as advocating for a policy, rather than faithfully and neutrally executing policy. This approach might be tempting because it aligns with a senior officer’s material incentives of ensuring their continued service, if not advancement in the military, unmarred by controversy. In this option, officers might begin by telling themselves they are protecting the institution by following whatever the current political trajectory is at the time, but in practice they end up moving the institution in a partisan direction and sacrificing their service’s professional values in the process.

To be fair, there is some validity in the idea that one can do more good working from inside than one can as a carping critic from the outside. But excessive careerism and self-preservation are not likely to protect the institution in the long run. Senior leaders rightly understand that not every issue is a hill worth dying on. But leaders must take care lest they deceive themselves into thinking that they are protecting the institution when they might just be protecting their own careerist ambitions. It is hard to judge motivations, even one’s own, and so this requires unsparing self-scrutiny coupled with regular accountability to something beyond one’s own opinion. As with any thorny ethical conundrum, it is important to identify objective standards in advance of circumstances and then use trusted advisors as sounding boards against which to measure one’s motives and calculations.

At this point, dutiful military leaders might throw up their hands in exasperation. What is it you would have us do, if you recommend against quiet quitting and rule out resignation in protest, trying to get fired, and trying not to get fired? The answer is walking a fine line that requires great care and delicacy but begins with internalizing a deep truth: There is no shame in getting fired when it is not for cause. In fact, preserving the integrity of the military profession might require accepting the risk that you will be fired because you did your duty.

The honor and reputations of those who have been fired are intact. The same cannot be said for those who would resign in protest or would sacrifice all of their professional ethics in the hopes of never getting fired.

In practice, this means, firstly, senior military officials should not pick fights. There are many policy hills where the dutiful thing is to accept change rather than die trying to preserve a position that is no longer viable in the new administration. The U.S. Army handled this well with respect to the debates in both the first and second Trump administrations about whether to hold a parade in Washington, D.C. The civilian secretary of defense worked to persuade Trump not to have a parade during his first term. It is the professional responsibility of cabinet officers to advise the president, and if they think the president is making a policy or political mistake, cabinet officials can push back in bureaucratic ways. In the current term, a different secretary of defense wanted the parade, and that changed the calculus decisively. Appropriately, the military saluted and obliged. Whatever one thought about the parade, it did not diminish military professionalism, in large part because Army leaders took great care to ensure that it showcased its people, culture, and values in an authentic manner.

It also means, secondly, that senior military officials should scrupulously observe the distinction between speaking up versus speaking out when professional values and ideals are in jeopardy. Civilians have the right to set policy, even if that policy is misguided; in short, they have the right to be wrong. But the military has the duty to warn them about the perhaps unintended consequences of policies. This should always be done by speaking up behind closed doors, directly to the civilian principal—not by speaking out to the press or on social media. This duty requires military officials to show moral courage and to take on risk that the advice will not be welcome, especially when the health of the profession is at stake. If senior flag officers remain quiet out of fear that if they spoke up they would be relieved, this should prompt a moment for reflection: Is protecting this professional norm or value worth getting fired over? To be certain, there are plenty of things that are not worth a dismissal, but every senior military leader should do the personal reflection to consider what they are willing to be fired over, and review that mental list from time to time as they encounter new professional challenges. Crucially, that list should not be empty.

Finally, senior military leaders need to find ways to communicate to the institution, particularly to the junior service members who look to them for cues on how professionals should act. This may be one of the most difficult challenges of all, especially in our digital age. Senior leaders must communicate in a respectful way that does not undermine civilian leadership—and if civilian leaders view even mild caution about a policy question as disrespectful, the need for tact is acute. But complete silence can be corrosive to good order and discipline and signal to the force that the military’s professional values and norms are expendable. Subordinates are very aware when their leaders go silent, and senior military leaders need to find ways to communicate internally about the profession’s values and standards. As they communicate, however, officers must be scrupulous about what they do and do not say. But they should accept more risk when they are speaking to the force about the military’s professional standards and values (as distinct from speaking about the behavior of their civilian superiors when the military should be extremely circumspect). At the end of the day, senior military officials are responsible for how the force under their command behaves and must steward the profession, no matter the political climate.

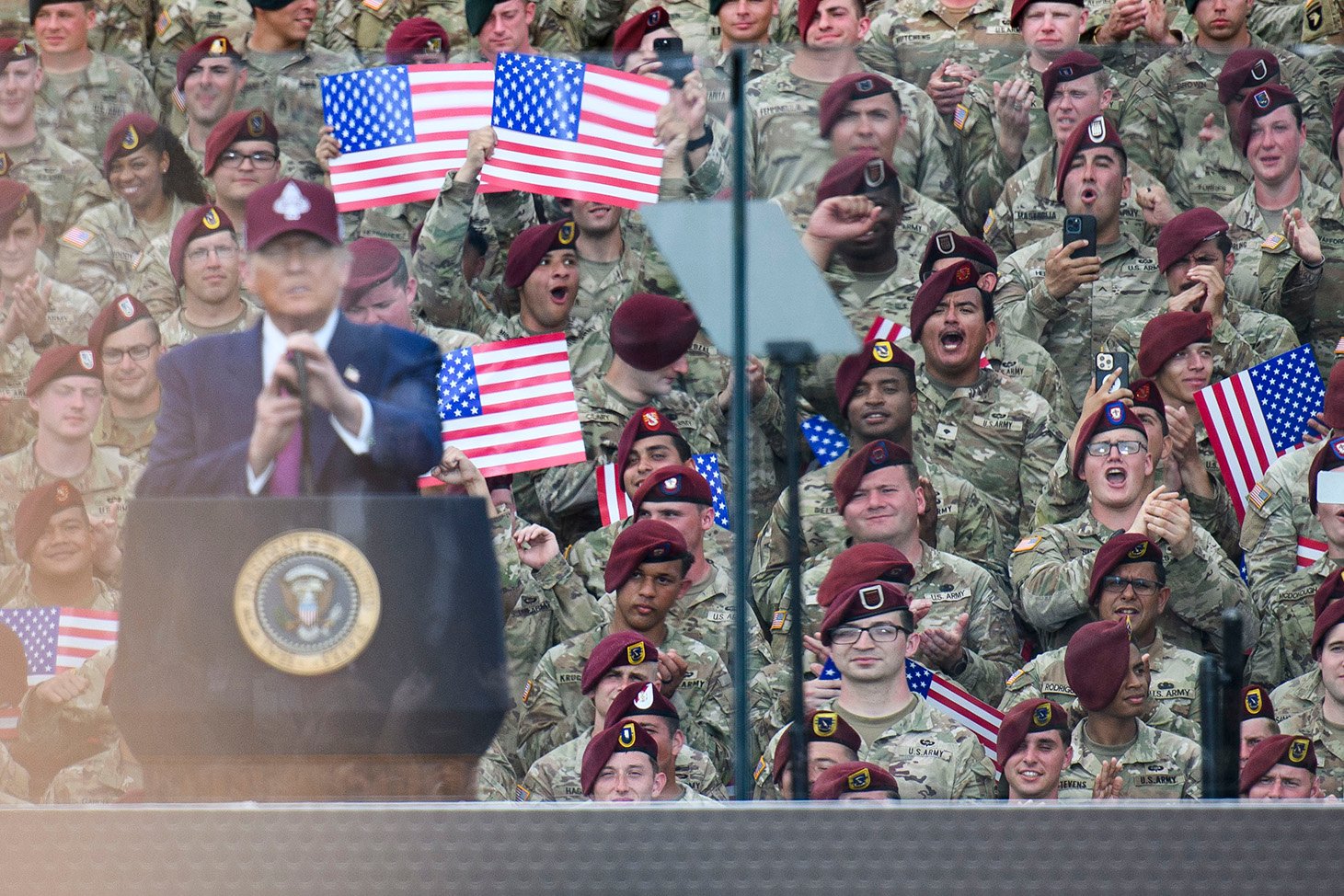

While no case perfectly captures all of the complexity, perhaps one recent example can serve to illustrate the distinctions and recommendations this approach advocates. Around the time of the 250th celebration of the founding of the U.S. Army, Trump traveled to Fort Bragg to give a speech. The speech ended up containing lots of partisan elements, and the troops’ boisterous reception did not distinguish between the partisan and nonpartisan elements. Numerous commentators criticized the event for politicizing a moment that should have been a nonpartisan celebration of the Army. However, senior political appointees in the Trump administration vigorously disagreed that there was anything inappropriate about the event at all. Here were all of the ingredients for a civil-military conflict that might produce more firings.

Applying the principles outlined above, we would offer the following prescriptions. In a situation like this: (i) Officers should not speak out about the president’s remarks nor criticize the partisan campaign style of the event; (ii) officers should quietly convey to the troops that their own behavior crossed a line and was inappropriate; (iii) officers in direct command of the units at the rally should accept more risk to their own careers in making sure the troops understand what was expected of them in such settings and how they could do better next time to honor the nonpartisan ethic of military professionalism; and (iv) the seniormost levels of the military should internally use this entire episode as a teaching moment. It will be hard to do this perfectly, and one can do it perfectly and still end up getting fired. If so, history will judge and recognize the care leaders took in living up to their professional duties.

Some may object to the forgoing by claiming the country is already in a civil-military crisis and so old norms like “do not resign in protest” or “do not push back in public against the administration” no longer apply. Some might argue that demanding that the military uphold norms when civilians are not is partisan in effect if not intent and so makes the military a partisan tool. We understand these concerns, but it is important to recognize they arise from a breakdown in civilian democratic institutions, and the military is not part of the system of checks and balances, no matter how respected or professional it may be. Moreover, a military that no longer upholds the norms that made the profession competent, subordinate, and trusted would only make matters worse. Better to leave this kind of politics to the political branches and stay mission-focused on what only the military can do.

In all of this, senior uniformed officials must maintain a delicate balance, guarding against two competing but fraught instincts: overreaction by falling on one’s sword over every slight and the death of the professional military ethic by a thousand cuts. The stakes are high. The military’s professional ethos is strong but not impervious to erosion, and it is either upheld or compromised based on the daily choices of its individual leaders under pressure. For generations, America’s leaders have understood that the real source of American military power is the integrity and caliber of its people. If that is lost, it could take a generation to recover it.

The post How Military Leaders Should Respond to Trump’s Norm-Busting appeared first on Foreign Policy.