Martin Suarez returned from a morning run in his Puerto Rican gated community in August 1994 to an assassin emerging from the shadows, a Smith & Wesson revolver heavy in his hand.

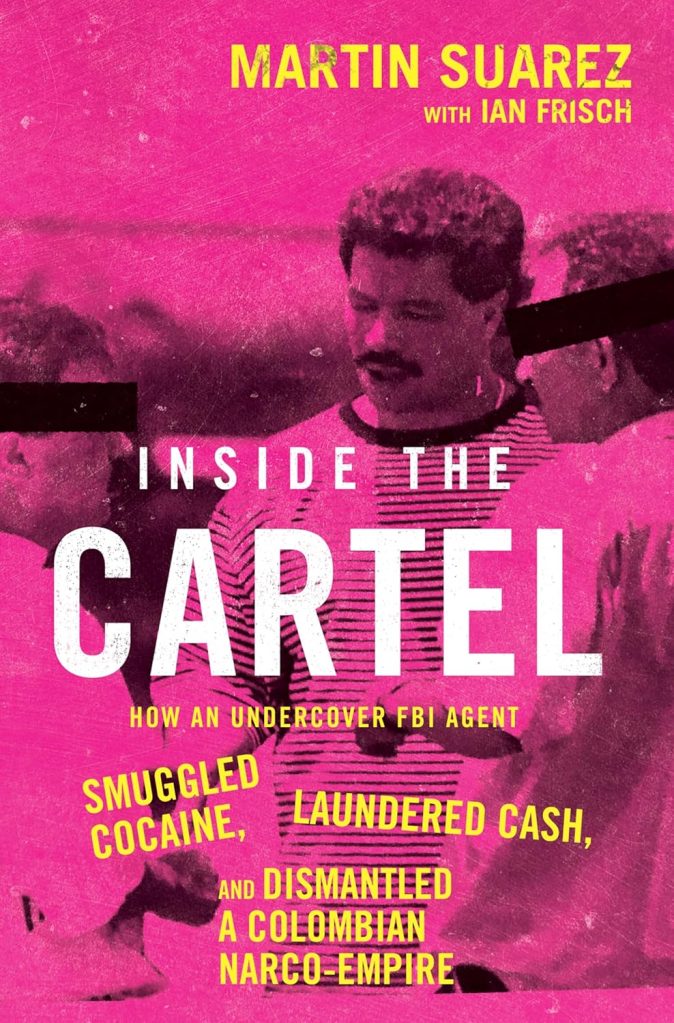

“Don’t run, motherf–ker,” the man shouted at him, as Suarez recalls in his new book, “Inside the Cartel: How an Undercover FBI Agent Smuggled Cocaine, Laundered Cash, and Dismantled a Colombian Narco-Empire” (Dey Street Books). “You aren’t going to outrun these bullets.”

Suarez, an FBI special agent with 23 years on the job, had faced Colombian narco-bosses, smugglers and killers, but this was different. The man pressing a gun into the back of his head was there to murder Suarez on his own doorstep, while his wife and two young sons were away.

He knew exactly who’d ordered the hit: El Toro Negro, the North Coast Cartel’s ruthless money boss. Toro had once warned Suarez, “At any time, I can reach across the world and tap you on the shoulder.”

Suarez had been infiltrating the Medellín and Cali cartels since 1988. Posing as “Manny,” a guy “who had no qualms helping Colombian cartels,” he’d smuggled $1 billion worth of cocaine into Miami by boat and plane (all of which federal agents would seize) and laundered millions for Toro himself.

“Not a gram of those drugs ever made it to the streets,” he writes. “We funneled every payment given to us by the cartel back into the government’s coffers. In essence, our investigation into the cartels was being funded by the cartels themselves.”

Suarez hadn’t planned on becoming “the first FBI agent in history to be thrown into a long-term, deep-undercover operation that targeted Colombia’s most ruthless drug cartels.”

By the mid-1980s, Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar had transformed the Medellín Cartel into a multinational empire, replacing coffee with cocaine as his country’s most lucrative export and flooding America with nearly 2 million pounds of product a year. Miami, Suarez’s hometown, became the cartels’ main point of entry.

“As the War on Drugs grew in scale and importance, even conducting thousand-pound busts wasn’t going to cut it anymore,” Suarez recalls. “The cartels were making so much money that they chalked up the losses to merely an overhead cost. The FBI needed to infiltrate the cartels.”

So the bureau built Suarez an office on Miami’s industrial south side, a warehouse that doubled as an import-export company. Outwardly, it was a produce business, moving crates of oranges and vegetables through the port. Inside, it was the launchpad for one of the FBI’s boldest infiltrations.

To pass as Manny, Suarez had to learn how to think, act and live like a smuggler. The FBI paired him with Diego, a cooperating witness and former pilot for the Medellín Cartel, who walked him through the cultural details that could make or break an undercover legend — how to do everything from spend money (“Don’t be cheap,” Diego said) to use the right vernacular. Instead of “son of a bitch,” for instance, a true drug smuggler would say “triple hijo de puta,” roughly translated as “triple son of a whore.”

“It doesn’t make much sense when you say it in English,” Suarez admits, “but it was how they spoke.”

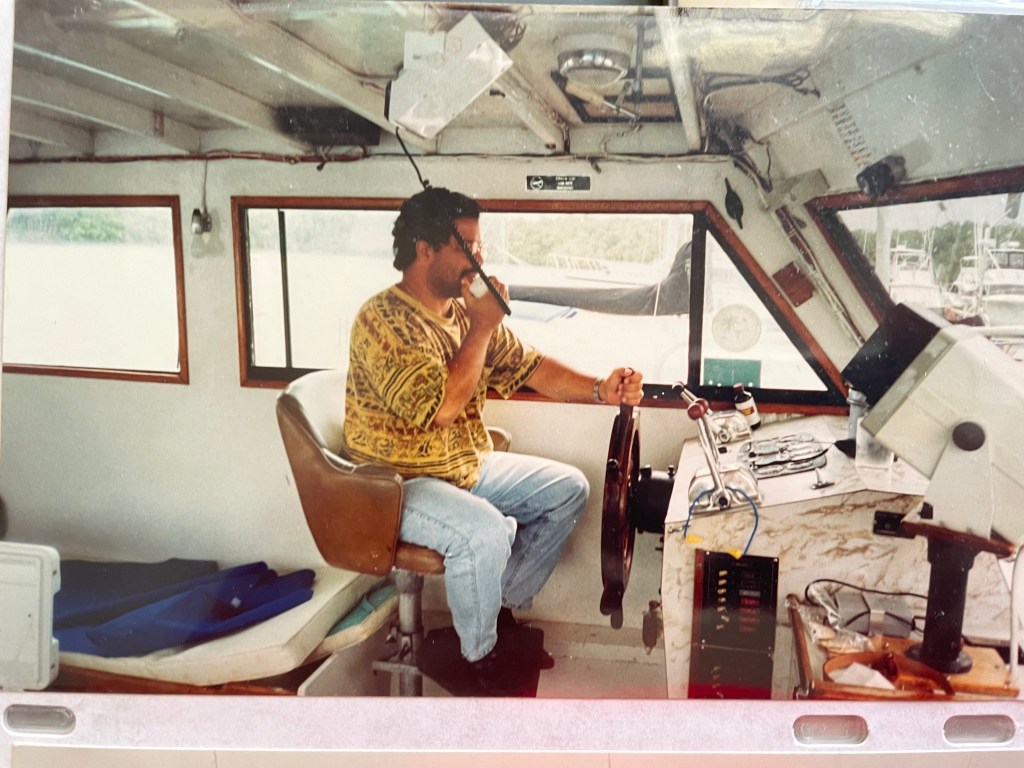

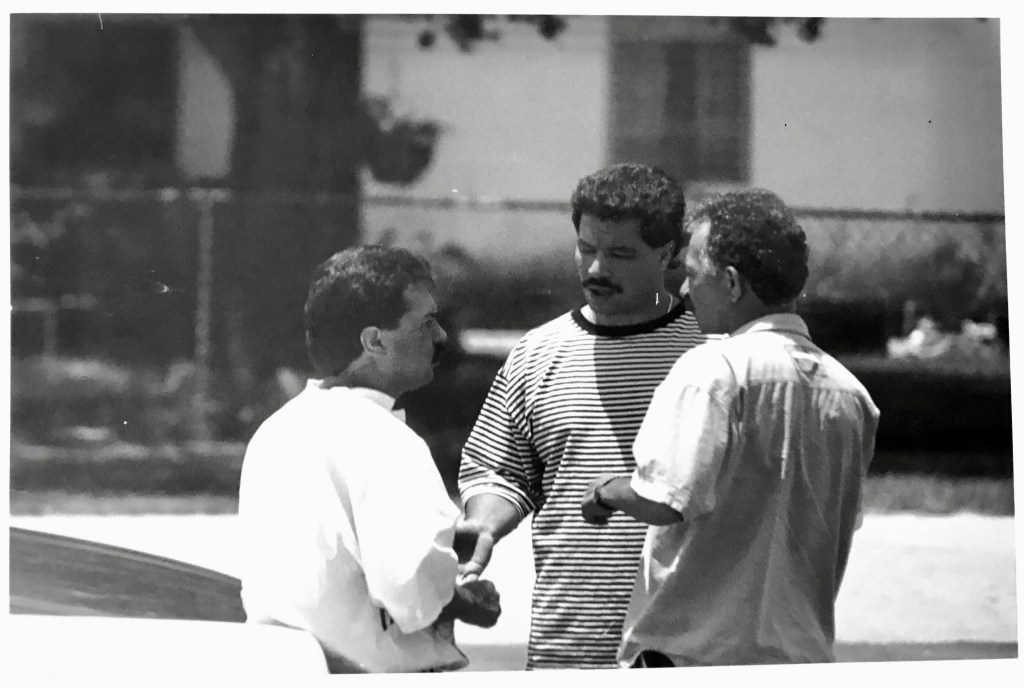

Suarez also needed to look like a high-rolling trafficker. “I stocked up on the finest European linen, Italian slacks, high-quality denim, cowboy boots, and tropical fedoras,” he writes. He grew a thick mustache, added a diamond-studded Rolex and a heavy gold bracelet to his wrist and slid behind the wheel of FBI-bought luxury cars: a gold Porsche 928, a black Porsche 911 Carrera S, a Bentley Continental.

“To complete the vibe, I put more swagger in my step. I ratcheted up my cockiness,” he writes.

Soon the façade became indistinguishable from the truth.

“In the eyes of the cartel, I was one of the most prolific drug smugglers in South Florida,” he writes. “I had marine and aviation skills, a reliable crew, and the guts to get their dope across the border.”

The cartels trusted him, couriers started showing up at his door, and Manny became a fixture in an underworld that was supposed to be impenetrable.

A typical “drop” looked less like a drug deal than a scene from an action thriller. His smuggling vessel was an inconspicuous 100-foot lobster boat, anchored at “specific coordinates” off Cuba’s coast. A 36-foot Mako fishing boat was his runner, darting into open water to collect the payload.

The handoff was simple on paper. Suarez would anchor the lobster boat, prep the Mako and wait for the cargo plane flying straight from Colombia. Once overhead, the crew would open its doors and drop tightly wrapped bundles of cocaine into the sea. Suarez would scoop them out before the Caribbean swallowed them whole.

In practice, it was chaos.

“A great whooshing came from overhead, the rippled squealing of a plane. The cartel had arrived,” Suarez writes. “And then I heard the sound: BANG! BANG! BANG!”

Each 45-kilogram bag of cocaine hit the ocean like a fridge hurled off a rooftop, landing so close to his vessel that one wrong angle could have destroyed it.

Suarez and his crew worked frantically as seawater poured onto the deck. “We took on so much water that the bales floated onboard and nearly washed back out to sea,” he recalls. For the next six hours, they hauled bundles aboard, chasing down stragglers swept away by the shifting currents. Missing even one would raise suspicion.

Other times a brush with danger was as simple as dinner. Suarez once sat down at a restaurant with Gustavo, a North Coast trafficker known as El Loco. Mid-conversation, El Loco’s wife, Ella, leaned in and whispered urgently, “We should get out of here. Those two guys, over there, they are feds. I can smell a cop from a mile away.”

Suarez froze. The two men at the bar were indeed federal agents. They were his men, running surveillance. To Ella, it was proof the walls were closing in. To Suarez, it was a reminder of how thin the line was between survival and exposure.

In August 1994, the FBI called the operation complete. “I threw away all my doper gear and money-laundering garb,” Suarez writes. “I crushed my undercover phones and turned my wire over.”

But he wasn’t out of danger. The sicario, Spanish for hitman, came within days. Suarez fought back, and shots were fired. “My back seized up and I felt blood on my face.”

The blood wasn’t from a bullet but from his busted nose. The hitman fled across a golf course, Suarez chasing and pulling the trigger. Click. He was out of bullets.

Suarez survived, and the shooting made local headlines, framed as a botched home invasion. Agents eventually caught the assassin, but he refused to talk. No one could prove El Toro Negro had ordered the hit, though Suarez never doubted it.

One month later, a US Attorney unsealed an indictment that landed like a thunderclap in federal court. Fifty-two members of the North Coast Cartel and its network of associates were charged with crimes from drug trafficking to money laundering. The list was “a who’s who” of the underworld: Daniel Mayer, Julio Tamez, the Moore cousins, Toro himself. It “made a bigger splash than a bale of cocaine falling from a plane and into the ocean.”

But El Toro Negro disappeared. “We never found him,” Suarez admits. “He slipped into the darkness of Colombia’s criminal underworld and never touched American soil. We were never even able to figure out his real name.”

Suarez returned to San Juan in 1996 and 1997 to testify in court, not as Manny but as Special Agent Martin Suarez. “When the defendants saw me enter the courtroom in my G-man garb — slick suit, trimmed hair, clean-shaven — they knew they were in deep shit,” Suarez writes. “Manny, a federal agent? It couldn’t be!”

The trials ended in convictions, and Suarez retired from the FBI in 2011.

Yet one name still lingers in his mind: Toro.

“He’s still out there. I suspect that he never forgot about me, the lone undercover FBI agent who crumbled the ground beneath his feet. I sometimes wonder if he continues to plot revenge, his long arm still laced with muscle, ready to tap me on the shoulder once more.”

The post A covert FBI agent smuggled $1B in cocaine to crush Colombian cartels — and lived to tell the tale appeared first on New York Post.