Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has decided that soldiers who received the Medal of Honor for helping gun down hundreds of Lakota Indians at the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre will be allowed to keep the military’s highest decoration.

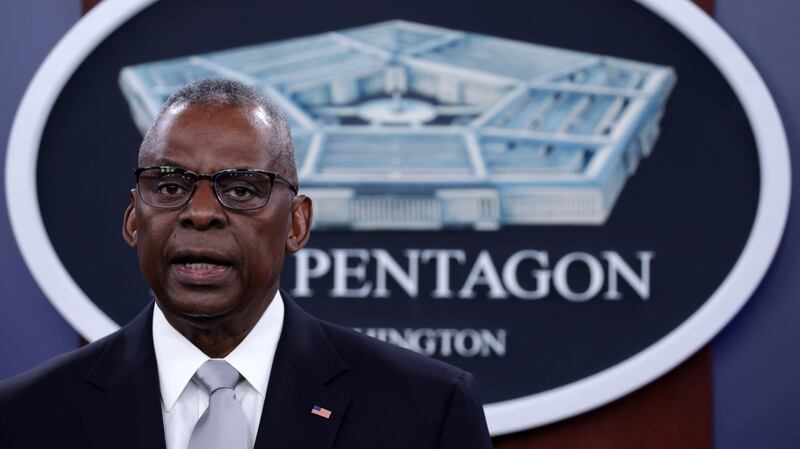

His predecessor Lloyd Austin had ordered a review last year in response to a 2022 congressional recommendation that the medals—which were awarded to 20 soldiers from the 7th Cavalry Regiment—be revisited.

“We’re making it clear without hesitation that the soldiers who fought in the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890 will keep their medals, and we’re making it clear they deserve those medals,” Hegseth said in a video posted to the social media platform X.

Although originally described as a “battle,” historical records show the U.S. Army killed between 150 and 300 members of a Lakota group called the Miniconjou—including women and children—even after the armed members of their group had already surrendered their weapons, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

The massacre was one of the final chapters of the Indian Wars between the U.S. government and the Plains Indians.

By 1890, the Lakota had lost 58 million acres of their land and been forced to live on a handful of neighboring reservations in North and South Dakota, National Geographic reported.

In 1889, Congress slashed the annual Lakota rations budget; a year later, a harsh winter and drought pushed the tribe to the brink of starvation, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

In response, many embraced a spiritual movement called the Ghost Dance, believing they could bring back their dead and reclaim their traditional hunting lands if they participated in ceremonial songs and dances.

The rituals were supposed to encourage the gods to return the earth to its natural state before the arrival of European colonists, and bury the non-believing white settlers underground.

It was the U.S. Army’s crackdown on the Ghost Dance movement—which white settlers worried would incite violence against them—that led to the Wounded Knee Massacre.

In December 1890, the U.S. Army banned Ghost Dance ceremonies and sent dozens of Native American policemen to arrest the Lakota Chief Sitting Bull, who had indicated that he would allow Ghost Dancers to gather at his camp in South Dakota.

Years earlier, in 1876, Sitting Bull had defeated the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

He resisted arrest and was murdered by one of the police officers. A group of his followers fled to join Sitting Bull’s half-brother Spotted Elk and his Miniconjou band at another reservation, according to National Geographic.

Worried the Army would kill more chiefs, the entire group decided to travel to yet another reservation. On the way, they were intercepted by 7th Cavalry troops, who escorted them to Wounded Knee Creek.

There, they were surrounded by about 500 more 7th Cavalry soldiers, who told the Lakota to lay down their weapons and said they would take them to a new camp.

It’s not entirely clear what happened next.

According to National Geographic, the Lakota thought they would be removed from their territory entirely and began to sing Ghost Dance songs. A dancer picked up dirt from the ground and flung it in the air, which the soldiers interpreted as a signal.

They began firing, discharging early machine guns and shooting women and babies at close range. The Lakota fought back but had mostly given up their guns, and even some who tried to flee were hunted down and shot, National Geographic reported.

Other accounts say the troops opened fire after a shot rang out, possibly because a soldier grabbed the rifle of a deaf Miniconjou named Black Coyote, who either didn’t understand or didn’t want to follow the order to turn over his weapon, according to Smithsonian.

The shooting continued for several hours, killing hundreds of Lakota and leaving 25 soldiers dead, many of them killed by friendly fire.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs nevertheless said the encounter had been a battle, and 20 soldiers were given Medals of Honor for various reasons, including bravery, efforts to rescue fellow troops, and “dislodging Indians” who were concealed in a ravine, according to the AP.

Starting in the 1970s, though, the incident became widely seen as a slaughter and not a legitimate military engagement. In 1990, Congress formally apologized to the descendants of the victims of Wounded Knee.

The massacre could have been revenge for the Army’s humiliating losses at the Battle of Little Bighorn, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Hegseth, however, insisted during his social media video that the Wounded Knee soldiers’ “place in our nation’s history is no longer up for debate.”

During his video, he claimed that the review panel Austin convened had issued a report reaching the same conclusion about the soldiers keeping their medals, but that the previous administration had kept the soldiers’ fate in limbo by refusing to act on the report.

“We salute their memory, we honor their service, and we will never forget what they did,” Hegseth said.

Reached for comment by the AP, a Defense Department official couldn’t say if the report would be made public. The Daily Beast has also requested comment.

It’s not the first time Hegseth has insisted on honoring ugly chapters of U.S. history.

Since taking the helm at the Department of Defense—which the Trump administration has given the secondary name of the Department of War—he has restored a Confederate monument that celebrates the slaveholding South and returned a statue of a Confederate general to a prominent place outside the Metropolitan Police Department Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

He has also renamed military bases after Confederate generals and reinstalled a giant portrait of rebel Gen. Robert E. Lee wearing his Confederate gray uniform and accompanied by an enslaved person.

The post Hegseth Declares Wounded Knee Massacre Troops Will Keep Medals of Honor appeared first on The Daily Beast.