Ever since the county of Los Angeles purchased one of downtown L.A.’s tallest skyscrapers, questions have mounted over whether the building could be vulnerable to major damage in the event of a massive earthquake.

County officials agreed to study the matter. But officials are now refusing to disclose a preliminary report that could shed light on the seismic safety question of whether the county should embark on costly retrofits to make it more reliable after a big earthquake.

This leaves the public in the dark — including those who currently work there and in adjacent buildings — as to what the taxpayer-funded report found. The report could offer more insight into the larger safety of other “steel-moment-frame buildings” that dot the Los Angeles cityscape.

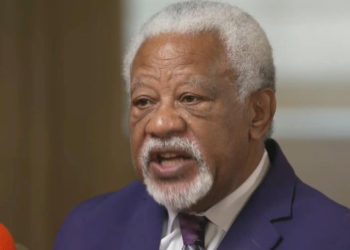

The head of the county’s Department of Public Works, Mark Pestrella, said at a public meeting this summer he expects the Gas Co. Tower, at 555 W. 5th St., would survive even the most powerful earthquake and the supervisors have said they believe it exceeds safety requirements.

But there remain real questions from others about whether the skyscaper suffered undiscovered damage during the Northridge earthquake in 1994, and whether another earthquake would render the tower so damaged that it would be unusable as the headquarters for the nation’s most populous county.

The County Counsel on Sept. 5 denied The Times’ request for a seismic report on the Gas Co. Tower, citing exemptions listed under the California Public Records Act. The seismic report was referenced in a Nov. 6 document recommending the county purchase the building, in which officials said they agreed with the report’s findings and recommendations, but didn’t elaborate on what they were.

The decision to refuse releasing the report comes as some elected officials have suggested they don’t support a retrofit, which carries an initial, rough estimated cost of $230 million. That’s more than the purchase price of the 52-story building, which the county bought in December for $200 million — just a third of the building’s pre-pandemic value.

The L.A. County Board of Supervisors on Aug. 12 voted to immediately suspend any work related to seismically retrofitting the skyscraper.

“We’re in some financial straits here in the county,” Supervisor Hilda Solis said during that board meeting. “What I wanted to make sure is that we are also taking more of a surgical look at how we are spending our money.”

The county is facing financial turmoil amid rising labor costs, a $4-billion sex abuse settlement and dramatic funding cuts from the federal government. Chief Executive Fesia Davenport emphasized at the Aug. 12 meeting that no money would be spent on seismic upgrades unless the supervisors agreed, and said she believed the upgrades were not necessary for the county to move into the building.

The county expects to have about 300 staff in the building by the end of the year.

“Safety is nonnegotiable, and my understanding is that the building already exceeds safety requirements,” Supervisor Lindsey Horvath said at the meeting. “In fact, it would have the highest standards of any county building at this present moment.”

In denying The Times’ request for the preliminary seismic report, county counsel said the county “is still in the process of considering prospective construction contracts.”

“As the process is ongoing, and the decision whether or not to award said contracts has not been made, the seismic report is not subject to disclosure at this time,” they wrote.

The county also characterized the report as both a confidential “attorney work product,” and a “preliminary draft” that is “being updated with new findings.” Disclosing the report now, officials contended, “would prejudice the prospective seismic retrofit project solicitation process.”

Some structural engineers argue that they have concerns that the Gas Co. Tower could be so heavily damaged in a major earthquake that it would be rendered useless to county officials.

And if the Board of Supervisors doesn’t allow further seismic study of the building, the county won’t be able to ascertain the potential risks of doing no retrofit work, some warn.

Considering the year it was built, “this particular kind of building — the steel-moment-frame-resisting building — has issues,” said structural engineer David Cocke, a former president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, and founder of the Gardena-based firm Structural Focus.

The Gas Co. Tower, built in 1991, was never required to be rigorously inspected for damage after the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake. The Gas Co. Tower incorporates a “steel-moment frame” as part of its structural system.

Such frames are made up of horizontal beams and vertical columns, and feature a largely rectangular skeleton. Steel-moment-frame buildings rely on the connections between horizontal beams and vertical columns to stay intact during earthquake shaking, keeping the skeleton of the building together.

During the Northridge earthquake in 1994, engineers were stunned to find severe damage in some steel-moment-frame buildings. That temblor significantly damaged 25 such structures, including the then-brand-new Automobile Club of Southern California building in Santa Clarita, which almost collapsed.

Northridge “showed us that the connections were susceptible to damage,” Cocke has said.

The city of L.A. required inspections and, if necessary, repairs of steel-moment-frame buildings in the San Fernando Valley. But the city never required the same of buildings downtown, despite the area also receiving a considerable amount of shaking.

During Northridge, some steel buildings in L.A. suffered such severe damage that their “columns were cracked halfway through,” Cocke said.

An in-depth study of the Gas Co. Tower would examine whether the building’s steel skeleton suffered any sort of damage during Northridge.

The Gas Co. Tower does have some structural advantages. It not only has a steel-moment frame, but a braced core. Cocke said he hasn’t been able to see the structural drawings of the tower but, in general, such a configuration is “probably going to perform [better] than an equivalent building that’s only a steel-moment frame.”

“I don’t think it’s going to collapse — that’s just my opinion,” Cocke said. “But I can say with a lot of confidence, in a major earthquake, they’re not going to be able to use the building unless they do the retrofit.”

The building code used at the time of the tower’s construction doesn’t necessarily meet today’s standards, according to Cocke. And in general, such buildings are only required to be built to a “life-safety” standard — meaning that occupants could crawl to safety, though the structures themselves may be damaged beyond repair.

“The building that they bought is going to provide a level of life safety, but there’s no guarantee that it will remain open and operational for the county’s services to the public unless they do this retrofit,” said Cocke, a member of the Structural Engineers Assn. of California.

County officials reiterated in a letter in September that they do recommend a voluntary seismic retrofit “to improve the building to current engineering standards,” but suggested that the initial estimate of the retrofit cost was only a rough one. To refine the price tag, the county Department of Public Works was soliciting bids for architectural and engineering design, project management and pre-construction services.

It’s similar to the process used to establish the actual cost to seismically retrofit the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration — the county’s existing headquarters — “and represents industry best practice for establishing seismic retrofit costs,” the county’s Chief Executive Office said.

The Department of Public Works had received proposals for the design and pre-construction work, “but they have not yet been opened,” the county said, and “the work is now on hold,” due to the Board of Supervisors’ Aug. 12 vote.

County officials said they can’t offer a better cost estimate unless they understand “the actual condition of the building’s connections and welds” — essentially, the areas of the building’s steel frame that connect with each other.

The county’s Chief Executive Office has maintained that the Gas Co. Tower is already safe, and any seismic upgrades are “proactive.” The estimated cost of retrofitting the new building is also far cheaper than the estimated $1 billion it would take to upgrade the Hall of Administration, a non-ductile concrete building that was built in 1960 and is vulnerable to collapse during a major earthquake.

At the Board of Supervisors’ Aug. 12 meeting, Pestrella, the county public works director, said he expects the tower would survive even the most powerful earthquake. In a magnitude 8 or above, he said most buildings downtown would see all their glass shattered, and major casualties would likely be from falling shards — not collapsing buildings.

“Within the building itself, you would be shook around so much that there could be incidental injuries to people from falling objects within the building itself,” he told the board. “But the structure itself should perform. It’s designed to perform and to remain standing.”

The Gas Co. Tower is not required to be retrofitted under city law. But Los Angeles is behind other cities in Southern California in requiring upgrades to such buildings.

Torrance, Santa Monica and West Hollywood all require steel-moment-frame buildings to be evaluated and, if necessary, retrofitted.

“Many of these buildings have not been retrofitted and may be susceptible to similar severe structural damage or even building collapse in a major earthquake,” the city of Torrance warns.

In a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault, it is plausible that five steel-moment-frame buildings — containing about 5,000 people — could completely collapse, according to a simulation from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Ten more of these buildings could be so severely damaged they would be “red-tagged,” meaning no one could enter them.

The city of L.A.’s landmark 2015 retrofit law did cover wood-frame apartments and brittle “non-ductile” concrete buildings, but elected officials opted not to include steel-moment-frame buildings, in part because they feared the cost, and in part because these buildings were seen as less of an urgent need to fix.

Still, the collapse of even one steel skyscraper would be catastrophic. The tallest members of California’s skyline have never been tested in a megaquake — on the scale of the magnitude 7.9 earthquakes that last rattled Southern California in 1857 and Northern California in 1906.

The county is working on an initial assessment involving limited testing and inspection of various parts of the Gas Co. Tower’s welded steel frame. That is estimated to cost $200,000, and will be paid for using revenue from tenants still renting out space in the building.

“We estimate the work will be completed in approximately three months. This work will not delay the move-in of county employees and will augment our understanding of seismic assessment work previously performed so that we are better able to quantify the cost of a seismic retrofit and make appropriate recommendations,” county officials wrote in a Sept. 2 letter to the Board of Supervisors.

But that short-term testing alone won’t be enough to nail down a more refined estimate of the retrofit cost, the county CEO’s office said.

The post Can one of L.A.’s tallest towers survive a huge quake? L.A. County won’t tell the public what its report found appeared first on Los Angeles Times.