On Sept. 9, the International Criminal Court (ICC) did something unprecedented: It convened a confirmation of charges hearing against Joseph Kony, the leader of the Ugandan rebel group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Kony faces a long list of accusations, including war crimes and crimes against humanity. The event was historic not because of the charges themselves—they were first issued back in 2005—but because Kony wasn’t there. This is the first time that the court has moved forward with a trial in absentia. The sight of prosecutors laying out their case before an empty chair only sharpened the central question: Why hasn’t Kony been captured?

That question has haunted the region for decades. The LRA has existed for nearly 40 years, and its leader has consistently outmaneuvered military offensives, manhunts, and political pressure. Despite the attention generated by the “Kony 2012” campaign, despite the presence of U.S. special operations advisors hunting him for six years, and despite a still-active $5 million bounty under the U.S. War Crimes Rewards Program, Kony is still at large. Thirteen years after his name briefly became one of the most searched on the internet, he continues to evade justice.

Kony survived by disappearing into some of the world’s most inaccessible borderlands and sustaining himself through a mix of illicit commerce and subsistence agriculture. Gold, ivory, and other contraband tied him into regional smuggling networks, while honey and small farms kept his fighters fed. Just as important were the alliances that he forged with local armed groups that helped him to slip away whenever his pursuers drew near.

The LRA emerged in the mid-1980s in northern Uganda, in opposition to President Yoweri Museveni’s new government. The group initially drew on spiritual beliefs, mixing Christian millenarianism with local cosmologies. But Kony’s rise was built less on ideology than on coercion. Recruitment quickly came to rely on abduction. By the mid-2000s, researchers estimated that the LRA had kidnapped roughly 75,000 people, many of them children. Boys were forced into combat units, while girls were enslaved as “wives” for commanders.

Fear was central to the LRA’s power. The group carried out massacres, mutilations, and village burnings, spreading terror across northern Uganda and beyond. For a substantial period, the Ugandan government was unable to protect the population, instead pushing them into forced displacement camps.

The violence made the LRA infamous. Yet it also made the group visible, and visibility proved dangerous. By 2010, pressure from the Ugandan military and regional forces compelled Kony to shift strategy: Large-scale massacres and abductions dwindled. The group retreated into some of the least-governed spaces in Africa: the remote borderlands between Sudan; the Central African Republic (CAR); and, to a lesser extent, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Most of the world only learned Kony’s name in March 2012, when the U.S.-based advocacy group Invisible Children released “Kony 2012,” a 30-minute YouTube film calling for his arrest. The video spread with unprecedented speed—more than 100 million views in its first week. Kony briefly became a household name, a rare case of an African warlord breaking into Western pop culture.

The campaign fueled a surge of policy attention. In 2011, the United States had deployed around 100 military advisors to support regional forces in tracking Kony. They brought drones, surveillance aircraft, and logistics capacity. For years, Ugandan soldiers, supported by the U.S. assets, scoured the bush. But the hunt came up empty. By 2017, Washington quietly wound down the mission. Kony remained, as ever, uncaptured.

This also underscored a deeper truth: finding a rebel leader in some of the world’s most inaccessible terrain, protected by fighters and shifting alliances, proved to be hard.

How, then, did the LRA endure once its days of mass raids were over? The answer lies in an improvised survival economy that tied the group into broader regional networks of trade, crime, and armed politics.

Central to this economy was ivory. The LRA targeted elephants in Garamba National Park in northeastern Congo, one of Central Africa’s last great wildlife sanctuaries. Tusks were hidden in caches across the borderlands, sometimes for years, before being smuggled out along trafficking routes. Gold and diamonds also entered the mix. The LRA bought minerals from local traders and resold them through transnational networks, acting as brokers rather than miners.

Not all revenue came from high-value commodities. Fighters cultivated small fields, planted maize and groundnuts, and harvested honey. Ali Kony—Joseph’s son, who was supposed to succeed him and styled himself as the group’s “minister of foreign affairs”—described to me during a 2024 interview how he used rocket-propelled grenade chargers as crude smoke bombs to drive bees from their hives.

Markets were the nodes that sustained this economy. Sometimes, the rebels slipped into existing local trading posts. In other cases, they created their own. One striking example was “Yemen,” a makeshift market in the Central African Republic near the Sudanese border. Accessible only by motorbike tracks and footpaths, Yemen became a hub where honey, gold, marijuana, weapons, and food all changed hands. The LRA’s main camp sat nearby, housing about 100 fighters and their families.

Trade was never just about survival: It also offered protection. By positioning themselves as intermediaries, the LRA rebels embedded themselves in regional smuggling circuits and armed-group networks. Deals with nomadic pastoralists and CAR rebels gave the group early warning and a degree of protection against government attacks.

Among these alliances, ties to Sudan were the most consequential. Since the 1990s, Khartoum had seen the LRA as a useful proxy against Uganda, which backed rebels in South Sudan. Even after formal support waned, the relationship never vanished.

Around 2009, as regional militaries closed in, Sudanese forces allowed Kony to shelter in Kafia Kingi, a contested enclave in Darfur. Formal protection from Sudanese forces may have ended, but commerce with individual Sudanese officers continued. Gold became the principal medium of exchange, while the appearance of weapons unusual for the borderlands suggested that channels to Sudanese suppliers remained open.

Despite all this, Kony had a $5 million bounty on his head. Why wasn’t this enough to tempt one of his allies to betray him?

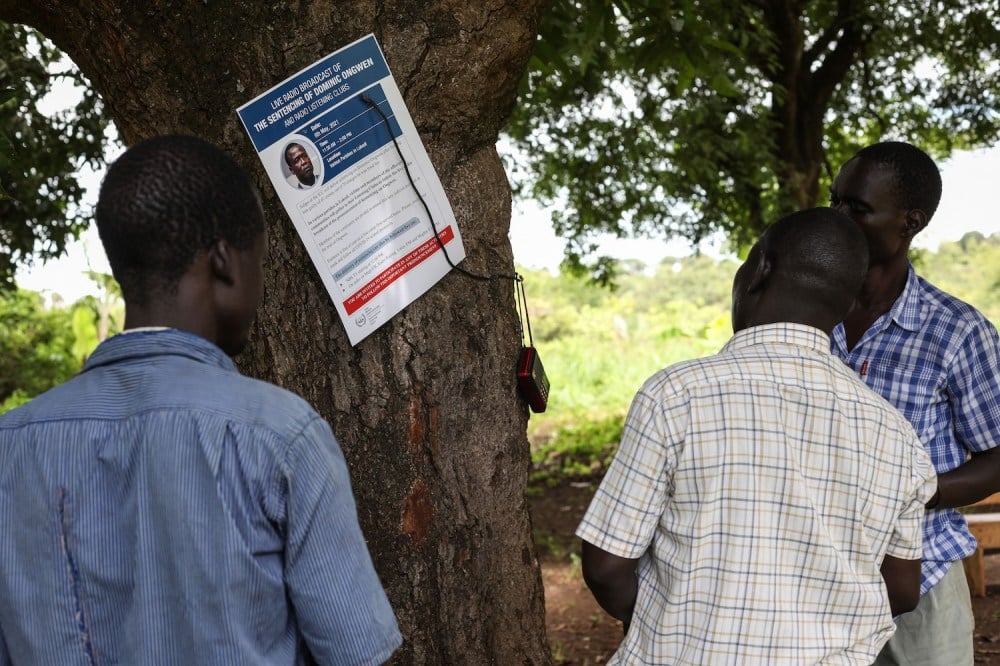

Part of the answer lies in mistrust. In early 2015, CAR-based Seleka rebels—a loose coalition of predominantly Muslim armed groups—captured Dominic Ongwen, another LRA commander with an ICC arrest warrant and a bounty on its head. They handed him to American forces and later tried to claim the $5 million reward. But they never received it, and the broken promise left a bitter aftertaste. For former Seleka rebels who regularly interacted with the LRA and operated in the same area, there is little incentive to risk turning Kony in.

Still, the LRA’s survival has not been cost-free. Attrition has steadily eaten away at its ranks. Morale among fighters eroded as years of hardship dragged on.

“Always on the run, always hungry,” one former combatant told me three years ago.

Others grew disillusioned with Kony’s endless and increasingly implausible promises of overthrowing the Ugandan government in Kampala.

Kony’s unpredictable and paranoid rule has deepened the despair. In 2007, he ordered the killing of his deputy, Vincent Otti, along with Otti’s loyalists. In 2013, more commanders were purged. Ongwen, the other indicted LRA commander, narrowly escaped as well, after Kony began to suspect him of having helped others to defect. The internal fissures reached Kony’s own family. Two of his sons, Salim and Ali, abandoned him—a particularly heavy blow to the movement.

The rebellion’s survival also came to depend on ever more grueling and risky missions: trekking across remote terrain in search of ivory or minerals. For many fighters, the costs outweighed the benefits.

In both 2014 and 2018, splinter factions broke away from Kony’s command. Disillusioned by Kony’s autocratic rule and tired of being sent on looting missions in the DRC and CAR without reaping the profits, they chose to strike out on their own. Based in the CAR borderlands, these splinter groups eventually decided to demobilize. In July and August 2023, a total of 164 fighters had laid down their arms—the largest mass defection in the LRA’s nearly 40-year history.

Amid all this, economic challenges deepened. The outbreak of civil war in Sudan in 2023 disrupted the borderland trade zones that the LRA relied on. With routes between the Central African Republic and Sudan cut, the group’s illicit commerce dwindled.

In these circumstances, Kony presides over a force believed to number only about 20 armed men, or at most a hundred people with women and children included. Once the terror of northern Uganda, the LRA now seems to be little more than a fugitive family compound in the bush: Kony has now elevated a new son into a leadership position—Candit Joseph.

Yet Kony himself remains elusive. Over decades, he has consistently outmaneuvered attempts to capture him. The International Criminal Court, which lacks its own enforcement arm, relies on state forces—and none have succeeded. Part of the reason is simple: Despite their notoriety, neither Kony nor the LRA rank high on any state’s priority list. In a region crowded with armed groups, they are dangerous but hardly the most dangerous. For surrounding governments, the LRA is more of a nuisance than an existential threat.

As recently as last year, Kony narrowly escaped two attacks on his base near the Yemen market, carried out by Russia’s Wagner Group and the Ugandan army. Each time, he seems to have been provided just enough warning to vanish.

That leaves the question of whether Kony himself will ever surrender. Health problems—including long-rumored diabetes, confirmed by people close to him, have not slowed him down. Former fighters are adamant: Surrender is not in his nature.

As one of Kony’s former “wives” told me just last week: “Kony will never come out; it will never happen. He’s a soldier; he wants to stay out there; he will never come before a court—he’s the one who wants to stay in charge.”

His son Ali, even after breaking with his father, put it in similar terms: “He’s a general; he will never surrender to this court.”

The post Why Hasn’t Joseph Kony Been Caught? appeared first on Foreign Policy.