Over the past two years, Chinese actors have used a gray market network of buyers, sellers, and brokers in Southeast Asia to circumvent U.S. restrictions on cutting-edge chips used for artificial intelligence and other high performance computing applications. Donald Trump laid the groundwork for controls on specialized AI chips in 2020, with restrictions seeking to prevent China from using Western technology for military advantage. But while the Biden administration substantially expanded the scope of these controls, it struggled to stop the rise of AI chip smuggling, with multiple cases over the past year involving bulk shipments worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Trump has the chance to seal the deal on the AI chip controls that he introduced, pushing Southeast Asian countries toward stronger enforcement using bargaining tactics like what he considers the “most beautiful word in the dictionary”: tariffs. Both improved corporate due diligence and local export enforcement programs in Southeast Asia would help counter Chinese AI chip smuggling, but these are backburner issues for most regional AI chip resellers and customs agencies. There is ample room for dealmaking here, and Trump’s willingness to recently let Nvidia and AMD continue exporting some cutting-edge AI chips to China with a 15 percent tax shows that he is open to unconventional arrangements mixing trade measures with export controls.

Despite the bundling of export controls into current U.S.-China trade negotiations, many U.S. policymakers still consider export controls of high-end AI chips to China to be “a frontline defense in protecting our national security,” as Republican Rep. John Moolenaar, chair of the House Select Committee on China, recently put it. To secure cooperation, the U.S. government must make a clear case that countering AI chip smuggling should be a Southeast Asian priority. With tariff negotiations top of mind for these countries, the administration can use the threat of higher tariffs to push governments to take this issue more seriously. And it need not only rely on sticks; it could sweeten the deal by offering partnerships on digital infrastructure and allowing countries that take measures to secure imported U.S. AI chips to import more of them, as was the result of the United States’ recent deals with Gulf states.

Southeast Asian leaders are no strangers to transactional diplomacy, and with countries lining up to strike trade deals with the United States, they will be eager to understand how to position themselves for a better bargain.

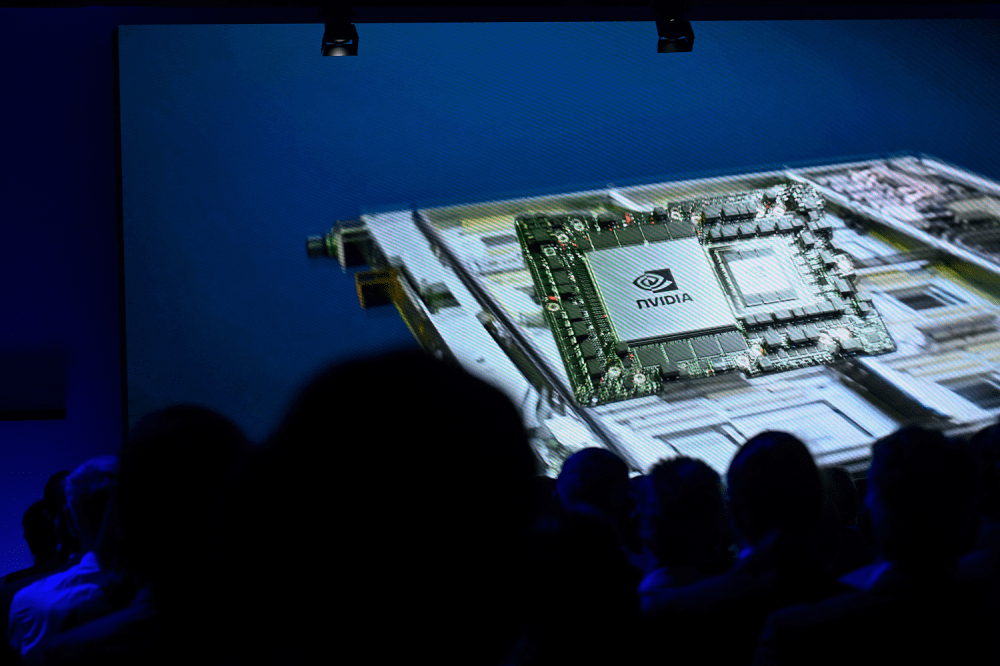

High-end chips like the Nvidia H100 and B200 are critical for developing advanced AI models, the latest battleground in U.S.-China tech competition. Leaders of these countries believe that advanced AI could transform economic and military domains by, for example, enabling powerful new offensive cyber and intelligence operations. Creating and deploying these advanced models requires tens or hundreds of thousands of cutting-edge AI chips, the best of which are exclusively manufactured in Taiwan from U.S. designs.

Some smuggling cases are small, like the Chinese student smuggling six Nvidia chips on a flight from Singapore, while others are large—like a Malaysia-based broker reportedly facilitating a $120 million order for servers powered by state-of-the-art H100 chips, or the three Singapore-based men arrested for allegedly committing fraud concerning servers worth around $390 million. But combined, these cases add up: In a report recently published by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) and co-authored by one of us at the Institute of AI Policy and Strategy (IAPS), we estimate that in 2024, smuggled AI chips provided China with more computing power than its domestic AI chips production. If all these smuggled chips were mounted in standard-size servers, they might occupy several hundred 20-foot shipping containers.

Smuggling tactics include shell companies, bribing customs officials, and concealing chips or servers with other shipments, as outlined in a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Elaborate schemes using these methods have already been uncovered in Malaysia and Singapore.

Another CNAS report identifies the aforementioned countries, plus Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, as potential smuggling hotspots due to close commercial ties with China and lax enforcement around AI chip smuggling. If U.S. policymakers want to avoid imposing additional restrictions on AI chip exports to potential smuggling hubs, they may need to strengthen enforcement cooperation with regional partners instead.

Getting enforcement right early is critical. Once a chip or server leaves the hands of a major supplier without triggering red flags, smugglers can easily move it undetected across borders. Local resellers often lack the capacity or willpower to conduct proper due diligence, so authorities must tackle the issue close to the source, focusing on the immediate customers of United States-based sellers, rather than tier-two distributors and end users who are downstream in the supply chain.

Targeting even just immediate customers is not something the United States can do alone. Southeast Asian customers of AI chip sellers span numerous countries and ports, and the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), the principal agency tasked with enforcing export controls, cannot be expected to police them all. The BIS is already famously understaffed: Across all Southeast Asia it has a lone export control officer responsible for inspections and compliance checks. It also has limited ability to prosecute violators outside the United States. Boosting the BIS’s funding and capabilities would help, which Trump’s proposed budget for this financial year does, but depending on the BIS alone creates a single point of failure in the anti-smuggling ecosystem.

The United States needs Asian allies and partners to step up if it hopes to prevent high-end AI chips from illegally flowing into China. Large-scale smuggling often happens via local resellers selling chips to shell companies run by smugglers.

Local export enforcement agencies in places like Malaysia could boost the BIS’s detection and enforcement capabilities and add important knowledge of localized tactics used in transshipment and reexport hubs. Having these agencies pressure local resellers themselves to perform more rigorous corporate due diligence, such as customer vetting and audits, could reduce the odds that they sell to smugglers, unwittingly or otherwise. Because small resellers lack the resources to do strict due diligence, local agencies could also provide next-gen know-your-customer and enhanced due diligence software tools, enabling them to go beyond surface-level information and look into financial flows and detailed contract histories of entities.

More ambitiously, the United States and partner countries could set up regional units dedicated to combating export control evasion. End-user verification programs focused on AI chip diversion, where local customs agents verify that goods are shipped and being used as intended, could drastically expand enforcement in the places where smuggling is most likely. And national governments could make it easier for the BIS to bring criminal cases and levy civil penalties against actors located in third countries. For example, U.S. investigators could be given rapid access to relevant documents and persons involved in smuggling cases, or U.S. civil penalties and forfeiture orders could be enforced against the violator’s assets in local courts.

Some of these efforts will require U.S. investment in local capacity building. But investing in smuggling detection is good value: It generates revenue by enhancing the U.S. government’s ability to detect and fine violators. Just as important, it strengthens the United States relative to China at low cost. There is simply no way at present to substitute for Nvidia’s cutting-edge AI chips: Huawei, for example, produces AI chips that are substantially inferior, and does not even have the supply to meet demand in China, let alone export to other markets. While that may change, China currently faces substantial bottlenecks, and with a surging global demand for AI chips, the United States will likely retain its chip-making market share for years to come.

To make this happen, the United States must persuade Southeast Asian governments that export controls matter—a perfect opportunity for Trump’s signature dealmaking style.

Export controls differ from typical Southeast Asian trade security measures, like screening import goods and collecting tariffs. Adopting novel enforcement measures will likely be too much hassle for Southeast Asian countries for them to do it purely out of goodwill for allies, especially when the United States’ position in the world order is unclear.

But Trump knows well the power of transactional diplomacy: If the United States needs Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries to align with its foreign policy goals, it must offer carrots (and sticks). Southeast Asian leaders are likely comfortable with a by-the-numbers approach, focused on tariff relief and market access rather than an appeal to values like democracy, freedom, and human rights, which creates openings for cooperation if both sides can make the math work.

Given recent negotiations, tariffs will be top of mind for Southeast Asian leaders. Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia saw April tariffs of 46 percent, 36 percent, and 24 percent respectively, and only recently negotiated them down to 20 percent for Vietnam and 19 percent for Thailand and Malaysia. With careful strategic messaging, Trump could use his favorite economic tool to persuade these governments that helping the United States counter Chinese AI chip smuggling is in their best interests. For example, with Malaysia’s $6.5 billion deal with Oracle at stake, the administration holds considerable leverage should it apply pressure.

These countries hope to benefit as foreign investment is displaced from China. The Trump administration could bolster the region’s fast-growing data center industry, as it did in its AI data center deal with the United Arab Emirates. It can also encourage U.S. firms like Intel to expand semiconductor manufacturing in countries such as Malaysia and the Philippines. This “friendshoring” of lower-end chip manufacturing—a shift of supply chains and investment towards allies and partners—would strategically divert business from China without transferring sensitive technology.

While the Trump administration’s reversal on H20 chip sales to China—collecting a 15 percent revenue share from Nvidia and AMD in exchange for export licenses—signals a willingness to negotiate over AI chip trade rights, it would be a mistake to think national security is no longer a priority. Trump has ruled out selling cutting-edge B200 chips to China, and the administration will keep working to better enforce export controls. If the administration wants ASEAN countries to align with its AI ambitions, it must appeal to their domestic priorities with proactive engagement. In this geopolitical landscape, Washington cannot afford to let the chips fall where they may.

The post How to Stop China’s AI Chip Smuggling appeared first on Foreign Policy.