Artyom Vovchenko had been conscripted into the Russian military, escaped in opposition to the war in Ukraine and ultimately made it to the United States, a country he hoped would offer him asylum and a new life.

But last month, he found himself on a layover at the airport in Cairo, frantically trying to avoid boarding a flight to Moscow. The United States was deporting him alongside dozens of other Russians after rejecting his pleas.

As the Egyptian authorities boarded the final people onto the deportation flight, Mr. Vovchenko, 26, loitered in the restroom, possibly hoping he could resist, abscond or somehow be forgotten. He had no such luck.

Egyptian guards pulled him out of the bathroom and roughed him up, leaving him with an injury on his forehead. They marched him onto the flight and to the back of the cabin, tying him to a middle seat. The plane soon began gliding toward Moscow. Mr. Vovchenko cried for much of the flight. He knew what would come next.

This episode was recounted by a woman who sat near Mr. Vovchenko on the plane and spoke to The New York Times, as well as by a man on the flight whose account was posted online by a Russian human rights activist.

Mr. Vovchenko’s plight represents a new reality for Russians who are struggling to persuade American judges to allow them to stay in the United States on account of their political or religious views. As President Trump accelerates deportations, some are being sent back to Russia, despite facing imprisonment or worse at home.

This summer, dozens of Russian deportees have been loaded twice onto mass deportation flights, a new phenomenon during the Trump administration. The Department of Homeland Security said it was saving taxpayer dollars by “efficiently flying illegal aliens to their home country on large fights.”

Mr. Vovchenko abandoned the Russian military in 2022, meaning he faced up to 10 years in prison. The Russian military, which had already accused him in a criminal case of disgracing his country by fleeing, is known for inhumane and life-threatening reprisals against deserters.

While detained in the United States for over a year, he had pleaded with officials to recognize the danger of sending him back to Russia, according to documents obtained by The Times detailing his case. But the nation that he had thought would be sympathetic turned out to be as unforgiving as his own.

“All of his claims were found to be meritless by a judge,” Tricia McLaughlin, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, said in a statement.

She said Mr. Vovchenko had tried to illegally enter the United States last year, and referred questions about his treatment in the Cairo airport to the Egyptian authorities. The Egyptian government did not respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Vovchenko’s deportation flight crossed into Russian airspace at the end of August. The woman on the flight, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of safety concerns in Russia, said she watched as he was taken away by Russian security officers at the airport.

No information about Mr. Vovchenko or his whereabouts has been made public since.

“The laws were stacked against him,” said Kenneth P. Primola, a lawyer who represented Mr. Vovchenko in his failed attempt to secure a U.S. court order protecting him from deportation because of expected harm in Russia.

“I thought sending him back was a death sentence,” Mr. Primola said. “I was kind of taken aback.”

Between Two Fires

Mr. Vovchenko’s journey, which The Times pieced together by interviewing six people familiar with it and reviewing documents, shows the perils of becoming caught between an authoritarian Russia gripped by war and a changing America carrying out an immigration crackdown.

It wasn’t just Mr. Trump’s mass deportation campaign that led to Mr. Vovchenko’s return to Moscow last month. Stricter border and detention policies that President Joseph R. Biden Jr. introduced also led to the removal, as did a fickle U.S. asylum process, where rulings often vary widely based on the judge.

The Times has withheld much of the information from the documents owing to concerns about Mr. Vovchenko’s security in Russia. His family members did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Mr. Vovchenko isn’t the first Russian opposed to the war to be imprisoned after being deported back to Russia from the United States.

Leonid Melekhin, who volunteered and protested for Aleksei A. Navalny, the Russian opposition leader, was arrested and charged with justifying terrorism after his deportation to Russia in July. Mr. Melekhin had been placed in detention and denied asylum in the United States.

Ms. McLaughlin, the D.H.S. spokeswoman, called both Mr. Vovchenko and Mr. Melekhin “illegal aliens” whom “even the open border Biden administration” kept in detention and did not release into the United States.

It is unclear how many of the Russians deported from the United States have since found themselves in the cross hairs of the Russian authorities.

Already, some have fled a second time.

Yevgeny Mashinin, a 28-year-old antiwar Russian activist, was deported from the United States in December after a judge rejected his asylum request. Days after he stepped off his deportation flight, the Russian authorities filed misdemeanor charges against him, accusing him of hooliganism and discrediting the military, and detained him for two days. After his release, he made a second escape, to France.

News of Mr. Vovchenko’s arrest, first revealed by Vladimir Osechkin, an exiled Russian activist who published the account of the man on the deportation flight, has prompted calls by Russian opposition figures in the West to protect antiwar Russian asylum seekers or to at least send them to safe countries. Some of those opposition figures have asked Canada to accept deported anti-Kremlin Russians.

Many Russians seeking safety in the United States are facing denials by U.S. judges who leave them unnecessarily in detention and do not acknowledge the danger they face if they are deported to Russia, said Dmitry Valuev, president of Russian America for Democracy in Russia, or RADR, a U.S. organization aiding Russian asylum seekers.

He cited the example of Svetlana Orzhevskaya and Igor Orzhevsky, mother-and-son Russian antiwar activists who were detained when they arrived in the United States last year. They were held despite their use of CBP One, a since-abolished app that allowed asylum seekers to schedule appointments to enter the country from Mexico, he said.

The activists argued that they should receive asylum because Russian prosecutors had filed multiple criminal cases against them related to their political views, which guaranteed years in prison if they were to be deported. A judge denied their claim. They remain in U.S. immigration detention in California, where they are appealing, Mr. Valuev said.

“The judges sometimes refuse to see the potential threat,” he said.

A Trapped Soldier

Mr. Vovchenko didn’t enter the Russian military by choice.

After studying at a law academy in Saratov, a city in southwestern Russia, he was conscripted in October 2020, before the full-scale invasion, for a year of military service. He was posted first in Russia and later at a Russian base in Armenia.

During his time as a conscript, his military service was extended by a year without his knowledge or agreement, to October 2022, according to the documents reviewed by The Times. Mr. Vovchenko’s parents lodged a complaint with the military prosecutor protesting this common coercive practice by the Russian Army to no avail. While he was serving this additional year, President Vladimir V. Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine, which Mr. Vovchenko opposed, according to the documents.

About a month before the forced contract was set to expire, Russian troops were routed on the battlefield, causing a hasty retreat. Mr. Putin signed a decree that called up 300,000 civilians and extended existing military-service contracts, including Mr. Vovchenko’s, until the end of the unspecified mobilization period.

Mr. Vovchenko was trapped.

When he heard that his unit would be sent to Ukraine, Mr. Vovchenko first visited his mother, who was dying of brain cancer, and then escaped, eventually making his way to Indonesia, according to the documents. Days after he left, his mother died.

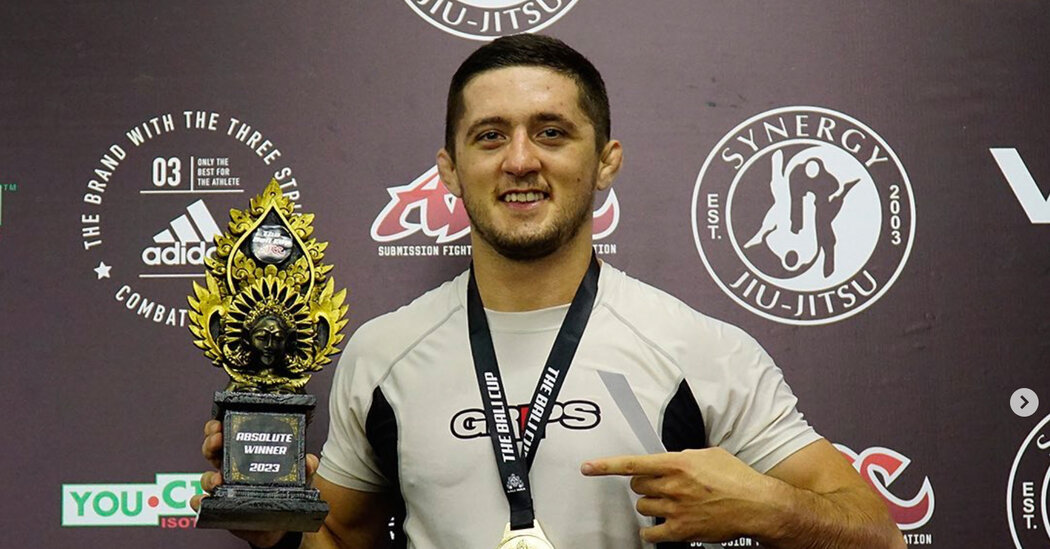

In Bali, he pursued a longstanding passion for jujitsu, participating in tournaments and calling himself a “peaceful warrior” on Instagram.

In March 2023, Russia and Indonesia signed an extradition treaty. The Russian authorities had filed a criminal case against Mr. Vovchenko for abandoning the military, the documents show, and had been harassing his father, sending letters denouncing Mr. Vovchenko and demanding his return. It isn’t clear whether Moscow filed an extradition request.

Seeking safety, he left Indonesia and traveled through seven countries, including Mexico, continuing to practice jujitsu along the way, according to the documents.

“I thought he was a really good person,” said Heather Woods, a jujitsu athlete who trained with Mr. Vovchenko in Mexico City and was impressed with his skill. “I felt he could have made a career there, or really in any country.”

In July 2024, Mr. Vovchenko approached the port of entry in Calexico, Calif., drove over the border and immediately declared asylum, according to the documents and a Russian man who befriended him in detention in Louisiana.

What he didn’t fully realize, according to his lawyer, Mr. Primola, was that Mr. Biden had drastically restricted the ability to seek asylum at the border with Mexico, except under a few extreme circumstances, in an executive order weeks earlier and a rule the year before.

The U.S. authorities also had begun detaining Russians who crossed the border to declare asylum and holding them indefinitely in detention centers instead of releasing them until the adjudication of their asylum claims, as had often been previous practice. The mass detentions came after eight Tajik asylum seekers, including at least one with a Russian passport, crossed the border and were investigated over potential ties to the Islamic State.

Mr. Vovchenko stepped over the border into a nightmare.

A Rejection

After apprehending Mr. Vovchenko, the U.S. authorities sent him to immigration detention centers in Mississippi and Louisiana.

Mr. Primola, his lawyer, said his client could not secure asylum because of the new border policies but was still able to apply for a “withholding from removal” order. Such a case requires a higher burden of proof of the risk of persecution in the destination country.

Mr. Vovchenko appeared in April at the U.S. immigration court in Oakdale, La., before Judge Jacob D. Bashore, a former military lawyer appointed to the court during President Trump’s first term.

According to TRAC, a research center that collects court data, Judge Bashore denied 89 percent of asylum claims from 2019 to 2024, far above the national denial rate of 58 percent. In the 2024 fiscal year, 85 percent of Russian asylum requests adjudicated by a U.S. court were granted, the center reported.

Mr. Primola said that the judge didn’t believe Mr. Vovchenko or care about his principled opposition to the war, and that he equated military service in Russia with that in America.

“This judge just didn’t think it mattered,” Mr. Primola said, describing his attitude as “Who cares? You got to serve, you got to serve.”

Mr. Vovchenko broke down into tears when his request was denied, his lawyer said.

A spokeswoman for the Justice Department declined to comment on the case. The court in Louisiana referred a comment request to the Justice Department.

Mr. Vovchenko decided not to appeal because he lacked money for a lawyer and did not want to spend as much as another year locked up, according to the Russian man who befriended him in the Louisiana detention center and other people familiar with the case. So he began trying to persuade the U.S. authorities to deport him to Indonesia, where he still had active residency, the man said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of safety concerns in Russia. Mr. Vovchenko appealed to the Indonesian consul for help, according to the documents.

But time was running out. Mr. Trump, now back in office, had begun his immigration crackdown, clearing out by the planeload people in detention centers marked for deportation.

Mr. Vovchenko was ordered onto a flight late last month.

The passengers sat in chains as the plane made its way to Egypt. Mr. Vovchenko’s only hope was that Egyptian officials at the Cairo airport would allow him to go somewhere other than Russia.

Mr. Valuev, the RADR president, said that previous deportations of Russians had not been done en masse and that Russians were sometimes able to negotiate a switch in destination with local officials during layovers.

“They can talk to them: ‘Can you give us our passports back? We will fly somewhere else. We don’t want to go to Russia,’” Mr. Valuev said. He noted that two anti-Kremlin Russians who were deported from the United States this month were able to persuade local authorities during their layover in Morocco to allow them to go somewhere else.

That option was not made available to Mr. Vovchenko and other Russians deported through Egypt on the two mass flights this summer.

Mr. Valuev said the flights should not be transporting Russian war dissenters to prison.

“People with criminal cases against them that are politically motivated should not be deported,” Mr. Valuev said. “They should receive some sort of protection.”

Oleg Matsnev and Hamed Aleaziz contributed reporting.

Paul Sonne is an international correspondent, focusing on Russia and the varied impacts of President Vladimir V. Putin’s domestic and foreign policies, with a focus on the war against Ukraine.

Milana Mazaeva is a reporter and researcher, helping to cover Russian society.

The post He Fled Putin’s War. The U.S. Deported Him to a Russian Jail. appeared first on New York Times.