On Oct. 16, 1962, U.S. President John F. Kennedy learned that the Soviet Union was building missile bases in Cuba. Soviet ships were on their way to the island nation, 90 miles off the Florida coast, “loaded with atomic missiles and warheads.” Kennedy and his team decided that the most effective response—and one that did not risk starting a nuclear war—would be a naval blockade of Cuba. In response, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev authorized the use of atomic weapons to prevent a U.S. invasion of Cuba.

As tensions built between Kennedy and Khrushchev, with each wanting the other to back down first, the United Nations’ Burmese secretary-general, U Thant, maneuvered himself into the role of negotiator. He had no mandate from the Security Council. Instead, he turned to the African and Asian delegates for support. With their backing, he approached both superpowers, seeking “to de-escalate tensions and create a window for diplomacy.” Racing to Havana from New York, fielding phone calls, and strategizing with representatives from the United States and Soviet Union, Thant’s efforts paid off. Global nuclear war was prevented.

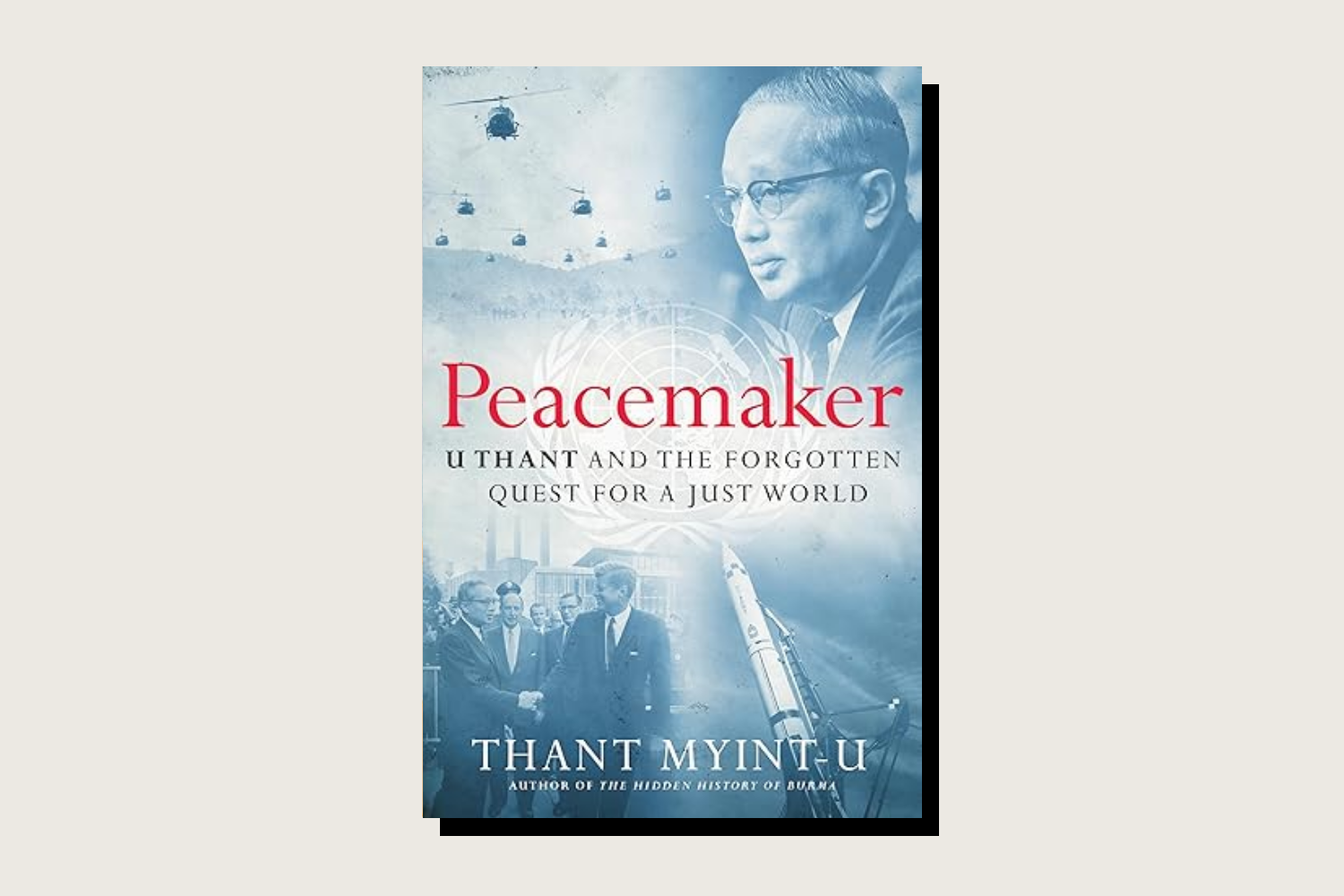

The historian (and Thant’s grandson) Thant Myint-U has brought together a compelling new narrative of U Thant’s tenure as the first Asian U.N. secretary-general during a turbulent time in international affairs. Peacemaker: U Thant and the Forgotten Quest for a Just World is full of nail-biting tension, as with the vivid rendering of the Cuban missile crisis—a difficult feat for an event with a known outcome. The biography sparkles with rich, human details about Thant’s New York existence, his inner life, and his changing psychology across two terms as U.N. secretary-general. His trajectory to leadership of the U.N. highlights the character traits that helped him—and, by extension, the rapidly expanding U.N. itself—to flourish during the early 1960s.

Thant started his career as a schoolteacher in Burma under British colonial rule. When the British left, Thant was in his 30s. He moved to Rangoon with aspirations to become a civil servant. He eventually became chief advisor to Prime Minister U Nu, which allowed him to travel the world. In 1955, he helped to organize the Bandung Conference in Indonesia which sought to preserve a non-aligned place for newly independent nations amid the growing tensions of the Cold War. By 1961, he had been Burma’s representative to the U.N. for four years, making a name for himself as a champion of Afro-Asian nations, but not as a radical. When the U.N.’s second secretary-general, Dag Hammarskjöld, disappeared in September 1961, presumed shot down by opponents of his peace efforts in what was then the newly independent Congo, the cool and pragmatic Thant was a favorite of both the Soviets and the Americans.

In the afterglow of his Cuban missile crisis victory, Thant made the U.N. cool, hosting dinner parties and contributing to a growing New York social scene where “professors, playwrights, and politicians” mixed with U.N. diplomats. Thant Myint-U describes a cosmopolitan U.N. scene in New York, but one that wasn’t without clashes. Before Thant, “[m]ost of the top-ranking officials in the Secretariat had never before served under someone who was not white.” Thant and other U.N. diplomats from non-white countries struggled to find accommodation in the city, with landlords blocking African and Asian dignitaries from renting their apartments.

Despite these setbacks, Thant was at his best when serving as a mediator between the two global powers. He could see what each wanted, how it fit into their global strategy as well as both domestic political pressures and personal leadership styles. His handling of the Cuban missile crisis was beyond compare, and he was able to position the U.N. as a particular type of force in the world during the crisis, recognizing that “for both Khrushchev and Kennedy, it was far preferable to accept an appeal emanating from the UN Secretary-General than to accept an ultimatum from the other.”

But the same qualities that served Thant so well during the Cuban missile crisis became his undoing over the next decade. Whereas being a scapegoat for Kennedy and Khrushchev allowed the two superpowers to make peace, by the later 1960s, Thant’s ability to negotiate on behalf of the non-aligned and Afro-Asian countries whose voices in global politics he sought to champion was undermined. As the crises of the decade spilled across the planet—in Congo, Vietnam, Israel-Palestine, India-Pakistan, Biafra, Bangladesh—the U.N. struggled to serve as both an advocate for sovereignty for the newly decolonized countries and to represent those countries in pleas for intervention. In dealing with the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), for instance, Thant pointed out that the leaders of newly independent countries in Africa “resent most…the patronizing or paternalistic attitude from outside,” when hegemons and former colonial powers treated them “as children who do not know how to run their affairs.” But not doing something was also a risk. In the Bangladesh Liberation War (1971), there was a “chorus of public calls for the UN to ‘do something,’” but Thant didn’t have the authority to do so.

Thant Myint-U sees U Thant’s foreign policy vision in opposition to Henry Kissinger’s supposed “realism”, calling Thant’s pragmatic “above all.” Kissinger was in opposition to Thant in more than just his approach: Thant Myint-U writes that as the secretary-general’s repeated attempts to negotiate peace in Vietnam had finally nearly succeeded in the summer of 1968, Kissinger—knowing that peace would torpedo Nixon’s chance at victory that November—quietly squashed the talks. In the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflicts in the Middle East, Kissinger “saw Israel as a valuable chess piece that could check any Soviet advance” into the region, while Thant felt that peace would mean that “the Arab states themselves would seek to lessen their dependence on Moscow.” But Thant and the U.N. had little power to compel the Nixon administration. Thant’s success as a peacemaker depended more on the United States and Soviet Union’s willingness to play along than it did on his skills as a diplomat.

Thant envisaged a future of “peaceful co-existence” between different, diverse types of governments—democracies, but also any number of other regimes—where “governments could work together in concrete and practical ways, most urgently to raise living standards around the world.” But while he could use his voice to raise awareness, he couldn’t change the foreign policy decisions that the United States made in Vietnam, Cambodia, or the Arab-Israeli conflicts that ramped up during his tenure. Increasingly, Thant found the U.N. sidelined to non-controversial humanitarian food relief or humanitarian campaigning.

Thant served out his second full term but had no illusions that the U.S. would support his candidacy for a third run. Although he left office in 1971 a celebrated figure, his death shortly afterwards in 1974 highlighted the tensions between his globally oriented vision and the domestic politics he sought to overcome. When his family returned to Burma with his body for burial, students and Buddhist monks seized on his presence as a focal point for a protest against the military dictatorship that had taken over the country. The government killed protesters, seized Thant’s casket, buried it under six feet of concrete, and “days of bloody rioting followed.”

The memory of Thant was effectively buried with him. The Americans and British, who, by the early 1970s, had been frustrated with Thant’s interference in their foreign policy aims, were happy to rewrite his role as “a passive Third World bureaucrat.” Thant Myint-U writes that, in accounts of the Cuban missile crisis, “Thant was literally airbrushed from history,” as transcribers of Kennedy’s tapes in the 1990s, who by that point were unfamiliar with Thant, misunderstood his name when it came up, writing “You [unclear].”

His dream of the U.N. as a place to transcend superpower dominance succumbed to a similar fate. The U.N. goal of sovereign states coexisting as equals in a representative global body had always been Thant’s, and every peacemaker’s, aspiration. But civil wars, secession movements, and land grabs challenged the idea that a sovereign state was a stable and predictable unit with which to negotiate. There were some spheres that Thant, and the U.N., could never reach—and not all governments were equally invested in a future of peace.

The post The Man Who Made the U.N. Cool appeared first on Foreign Policy.