The Trump administration’s assault on America’s universities by cutting billions of dollars of federal support for scientific and medical research has called up from somewhere deep in my memory the phrase “duck and cover.” These were words drilled into American schoolchildren in the 1950s. We heard them on television, where they accompanied a cartoon about a wise turtle named Bert who withdrew into his shell at any sign of danger. In class, when our teachers gave the order, we were instructed to follow Bert’s example by diving under our desks and covering our necks. These actions were meant to protect us from the nuclear attack that could come, we were told, at any time. Though even in elementary school most of us intuited that there was something futile in these attempts to shield ourselves from destruction, we dutifully went through the motions. How else could we deal with the anxiety caused by the menace?

The anxiety greatly increased in October 1957, when Americans learned of the Soviet Union’s successful launch of the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1. The vivid evidence of the technological superiority in rocketry of our Cold War enemy provoked a remarkably rapid response. In 1958, by a bipartisan vote, Congress passed and President Dwight Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act, one of the most consequential federal interventions in education in the nation’s history. Together with the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, it made America into the world’s undisputed leader in science and technology.

Nearly 70 years later, that leadership is in peril. According to the latest annual Nature Index, which tracks research institutions by their contributions to leading science journals, the single remaining U.S. institution among the top 10 is Harvard, in second place, far behind the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The others are:

-

The University of Science and Technology of China

-

Zhejiang University

-

Peking University

-

The University of Chinese Academy of Sciences

-

Tsinghua University

-

Nanjing University

-

Germany’s Max Planck Society

-

Shanghai Jiao Tong University

A decade ago, C.A.S. was the only Chinese institution to figure in the top 10. Now eight of the 10 leaders are in China. If this does not constitute a Sputnik moment, it is hard to imagine what would.

But if America’s response to Sputnik reflected a nation united in its commitment to science and determined to invest in the country’s intellectual potential, we see in our response to China today a bitterly divided, disoriented America. We are currently governed by a leader indifferent to scientific consensus if it contradicts his political or economic interests, hostile to immigrants and intent on crippling the research universities that embody our collective hope for the future. The menace now is within. And with very few exceptions, the leaders of American universities have done little more than duck and cover.

The N.D.E.A. reflected the widespread realization that something had to be done in schools and universities besides teaching students to hide under their desks. The country urgently needed more trained physicists, chemists, mathematicians, aerospace engineers, electrical engineers, material scientists and a host of other experts in STEM fields, and the government grasped that to get them would take a massive infusion of money pumped into schools and universities: roughly $1 billion, the equivalent of more than $11 billion today.

From the start, this government investment in education wasn’t free of ideological interest. It was fueled by fear — fear of the Russians, fear of the atomic bomb, fear of falling behind in the “space race” — and intended to influence curricula. Not, to be sure, in the catastrophic manner of the Soviet Union, where Trofim Lysenko’s theories of genetics set back Soviet biology for decades, but rather by strengthening science departments across the country.

Until 1962, recipients of N.D.E.A. funds had to sign an affidavit affirming that they did not support any organization that sought to overthrow the U.S. government. But in one of those moments in which the right policy is chosen for the wrong reason, Southern segregationists in Congress, worried that some of the funds might be used to further desegregation efforts, added a provision stipulating that no part of the act would allow the federal government to dictate school curriculum, instruction, administration or personnel.

The act also played a significant role in diversifying the nation’s campuses by providing low-interest loans to applicants in need, incidentally challenging policies that had restricted admission for disfavored groups, such as Jewish, Asian, Black, Polish and Italian students. Halfway through my undergraduate years in the early 1960s, Yale acquired a new president who quickly brought about many changes, including the dismantling of the old antisemitic ethos and the admission of more students with last names that would have led to their rejection.

These transformations wound up playing a significant role in my own career. When I went back to Yale for graduate work, the N.D.E.A. funded my Ph.D. The government was not under the illusion that studying Shakespeare was rocket science. But Title IV of the act, calling for an increase in the number of university professors, extended support to the humanities as well as the sciences. Sputnik had turned out to include me in its orbit.

What began as a project of national security blossomed into a generator for limitless curiosity, creativity and critique. A seemingly unending succession of inventions and discoveries emerged with the support of the laboratories and research institutes of American universities: the internet, the M.R.I., recombinant DNA, human embryonic stem cells, CRISPR genome editing, the contributions to mRNA technology that made a new generation of vaccines (including for Covid-19) possible, and on and on, along with epochal breakthroughs in our understanding of matter and the origin of the universe.

The result of the huge influx of tax dollars was institutions that not only trained scientists, medical researchers and weapons engineers but also cultivated sociologists, historians, philosophers and poets. The American university is uniquely structured to break down walls between STEM and other intellectual pursuits, both in the undergraduate curriculum, where students must almost always fulfill general education requirements, and in the campus culture.

Traditional research boundaries began to fall. At the University of California, Berkeley, where I was hired in 1969 and taught for several exciting decades, an imaginative dean sent around a questionnaire asking members in the science faculties whom they most liked to talk with about their current work. In light of the answers, departments were reorganized. Innovation flourished. The parking lots outside the science buildings had multiple spaces reserved for “N.L.s” — Nobel laureates.

By the 1990s, American universities had become global cultural icons — envied for their intellectual breadth, celebrated for their academic freedom and eagerly sought after by international students who viewed them as the apex of open inquiry and prestige. The government hadn’t intended to create autonomous, cosmopolitan knowledge institutions, but the scale of its investment — and the relative insulation of universities from direct political control — helped to make those institutions into supreme civilizational achievements.

Heady with their success, elite universities began to dream that they could do more than teach and produce new knowledge. They longed to cure all the ills that beset society: to rectify the injustices in our past, to heal the harms in the present, to promote equality in the future. Caught up in this dream, they made little effort to persuade the public that their new policies were beneficial.

And now, notwithstanding its triumphs, the whole enterprise is in serious trouble. The Trump administration began its assault by using the pro-Palestinian demonstrations on many campuses to charge elite universities with antisemitism. The rationale has largely shifted to complaints about affirmative action, diversity initiatives, liberal bias and the like. Scientific research has been curtailed; postdoctoral fellowships have been abruptly canceled; laboratories have been shuttered and visas denied. The damage to scientific enterprise extends beyond our borders, whether it’s from the cancellation of nearly $500 million in funding for mRNA research under the health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — a kind of Lysenko lite — or the purging of data on which climate researchers around the world depend. We will never know what diseases might have been cured or what advances in technology might have been invented had the lights not gone out in the labs.

Several universities have now paid what amount to enormous fines in the hopes of restoring at least some federal support. But that restoration is not guaranteed; the administration has often conditioned it on demands that intrude on precisely the areas of university life — curriculum, instruction, administration, personnel — that the N.D.E.A. prohibited the government from touching.

Should the Trump administration settle for one-time fines, universities, chastened by the threats of the past few months, may yet recover their footing. But if, as seems entirely possible, the administration is determined to reshape the intellectual life and values of faculty members and students alike, then such recovery will be impossible.

Why on earth would we abandon institutions that have genuinely made America great? Why would we squander the world’s admiration for this magnificent achievement of ours? Why would we put at risk laboratories that are working to cure cancers or perfecting artificial limbs or exploring deep space or testing the limits of artificial intelligence?

Our situation is not hopeless any more now than it was in 1957. The United States has won so many Nobel Prizes — far more than every other country, including China — not only because of generous funding but also because of an intellectual culture that encourages and rewards innovation and risk-taking, and because we have attracted gifted researchers from all over the world.

For the moment, American universities still have the enormous advantage of their resources and their autonomy, and their joyous imaginative freedom. I walk through Harvard Yard on my way to teach a freshman course on great books from Homer to Joyce, and I am continually astonished by what I see and whom I meet. There are students from all over the world — from Mongolia as well as my hometown, Newton, Mass., from Athens in Ohio and Athens in Greece — and there are colleagues who have been immersed in a wide range of pursuits, from creating the first image of a black hole in space to deciphering the words on a scrap of ancient papyrus. We need to get up from under our desks and persuade our fellow citizens that the institutions that they have helped create with their tax dollars are incredibly precious and important.

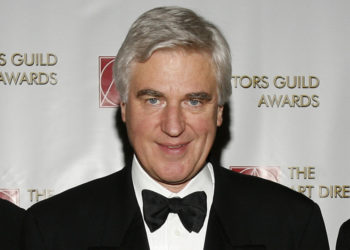

Stephen Greenblatt is the author, most recently, of “Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post We Are Watching a Scientific Superpower Destroy Itself appeared first on New York Times.