Mary Roy lay in a temperature-controlled coffin with a glass top in the dining room of her house in Kottayam in September 2022. Press photographers and a group of mourners gathered around her body. Many knew her as the founder of a progressive school and as a feminist who had challenged inheritance law, winning equal rights for Christian women in the state of Kerala after a protracted, decades-long battle in the Supreme Court of India. Arundhati Roy knew her as a tormentor and abuser, a “local mafia don,” a cult leader, a jealous and vindictive mother, and the writer’s most “enthralling subject.”

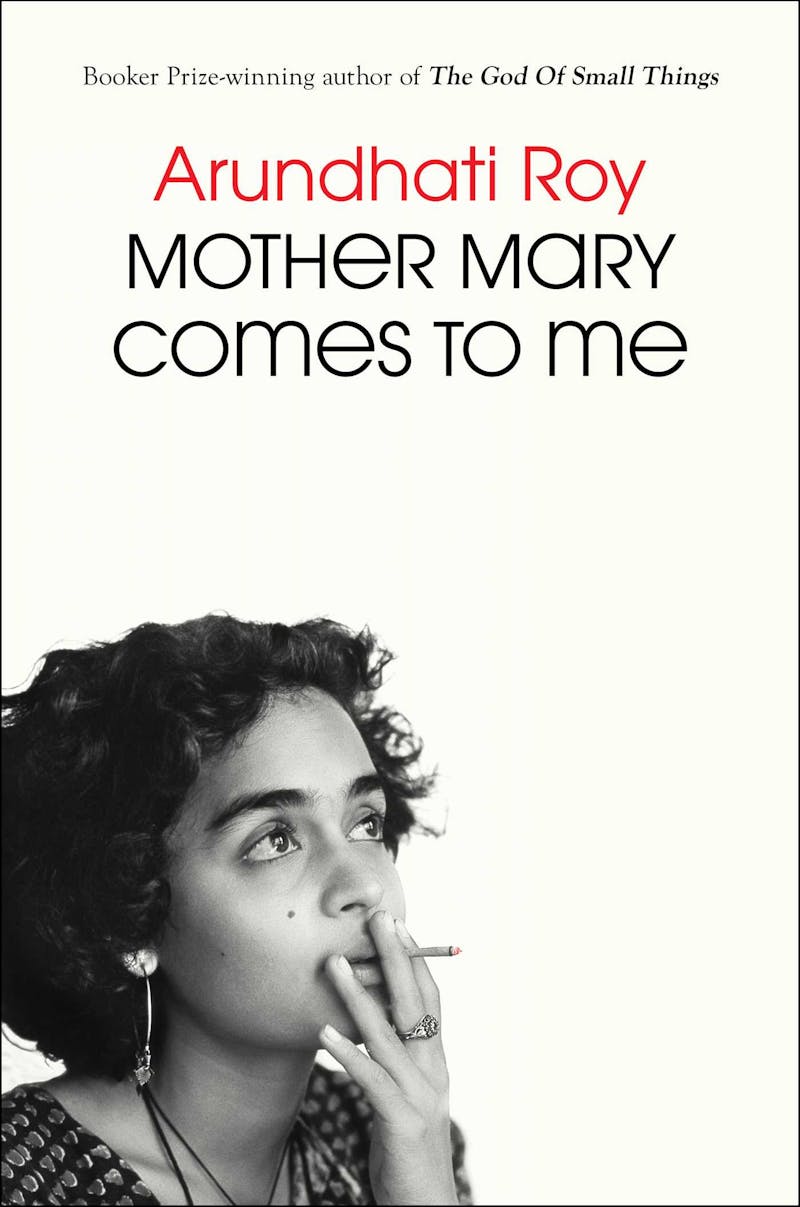

Mrs. Roy—as the matriarch instructed her son and daughter to address her—left a unique inheritance for them, a gift of darkness. “I learned to keep it close, to map it, to sift through its shades, to stare at it until it gave up its secrets,” Roy writes in her new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me. It is a statement that could very well be about the process of writing itself, especially for Roy. Since her Booker Prize–winning novel, The God of Small Things, was published in 1997, earning her global fame, Roy has written more than 10 works of nonfiction—on environmentalism, nuclear weapons, the rise of Hindu nationalism, the war on terrorism, and more—along with a second novel, 2017’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. These days, she is considered as much an activist as a writer—though she dislikes the term writer-activist, which sounds, she says, “like a sofa bed.”

In 1969, when she was nine years old, a newspaper photo of a severed head made an impression on young Roy. The head belonged to a landlord near Kottayam whom the Naxalites had slain. The far-left Maoist insurgents were proponents of armed revolution and believed in the annihilation of class enemies. Four decades later, Roy would go into the Dandakaranya forest with the Naxalites to write about land taken from Indigenous tribes and given to corporate mining companies by the government. The day before she went, Mrs. Roy, who didn’t know about the trip, called to say, “I’ve been thinking … what this country really needs is a revolution.” Darkness, in this memoir, is not merely relegated to Mrs. Roy’s treatment of her daughter. It is a value system from which politics and writing emerge. And for Roy, that “turned out to be a route to freedom, too.”

The image of Mrs. Roy in her glass-top coffin is one of many that are as striking as she was singular: she, bedridden in a high iron cot, covered by a thick metallic-pink quilt and heaving from asthma attacks when Roy was a child; fast-forward to the matriarch in her seventies, her hefty body being carried on a stretcher from the ICU to another floor like the steamship “from Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo”; and then perched again atop a lofty bed, “swinging her legs like a schoolgirl, wearing an oxygen nasal cannula, her diamond earrings, a size 44DD lilac lace bra”—which John Berger (yes, that John Berger, of Ways of Seeing) helped Roy shop for in Italy—“adult diapers, and a pair of high-top Nike basketball shoes.” Sitting beside her, Roy wonders how her life could ever be normal. This, too, is a complicated gift, but a gift nonetheless. Being basic, in this day and age, is an epithet.

Yet for all Mrs. Roy’s charms, the transference of indignity and anger she suffered from others onto her children was a choice she too often made throughout her life. She mocked Roy, called her a bitch in public, blamed the child for her asthma and, consequently, her imminent death; she often kicked her out of the house or left her on the side of the road. She ordered Roy’s older brother to go kill himself. She told Roy that, when someone asked her after The God of Small Things was published if she was Arundhati Roy’s mother, she felt as though she had been slapped, and she did her best to sabotage an event for the book’s launch. It’s no wonder she is endowed with the appellation Mrs. Roy instead of mother throughout the memoir. Roy, as a little girl, would tell her asthmatic and wheezing mother that she would breathe for her, that she would become one of her lungs. Roy became a hostage who took on the burdens of another, her whole body given over to exist as one charged organ responsible for two lives. If Mrs. Roy died, she would, too.

In one uncanny scene, Mrs. Roy’s sister-in-law, Jane, nearing 90 and showing signs of dementia, mistakes Roy for her long-ago pregnant mother and says, “I know you don’t want that baby, Mary, but, really, it’s too late for anything now.” Mrs. Roy had been miserable upon the discovery of her second pregnancy and had not hidden this despondency but instead described to her daughter her varied attempts to abort the fetus by eating green papaya and using a wire coat hanger. “I wish I had dumped you in an orphanage,” she’d say. This casting by Jane, of Roy as her own pregnant mother, could be an episode of Black Mirror called, “What if you were pregnant with yourself and wanted an abortion?” Darkness turns to black. Perhaps Roy’s own successful abortion as a young woman was influenced by her mother’s warnings about “drifting into a life of marriage and children without thinking it through carefully.”

The darkness that beget darkness: As a child, Mrs. Roy endured her father’s whippings and was habitually kicked out the house. Her father once split her mother’s scalp open with a brass vase. The quickest escape route was to marry the first man who proposed to her. Micky, who fathered Roy and her older brother, Lalith Kumar Christopher (known as LKC), was a drunk whose habit of drinking bootleg liquor mixed with varnish “burned through his intestines and turned them to lace.” He died from internal hemorrhaging. Mrs. Roy remarked with disinterest upon hearing of his death, “Poor fellow. He was such a Nothing Man.” They had separated when Roy was about three. She wouldn’t see him again until nearly two decades later. The Nothing Man was less a father than an image from a photo in a gray album that the Roy children would look at, a man who was known for sitting and blowing spit bubbles for hours on end while staring into space, who was so frail and malnourished he resembled, according to Roy, the people in U.N. pamphlets. When reunited with his adult children, he begged them for money, presumably to buy more varnish-hooch.

A Nothing Man, however, was surely better than another kind of man whom Roy had known—fathers who wielded power with fists and humiliation. She recalls a friend’s mother bending down, her diamond earrings beaming, in front of the family patriarch to pick up a letter he had thrown on the floor for her to retrieve. In this scene, Roy locates the utter loneliness of dehumanization—a pure spectacle of shame. And in recollecting other friends’ mothers who always seemed frightened, tentative, awaiting instructions, Roy knew that the difference between them and Mrs. Roy retained some value.

Another heirloom of darkness was bestowed when Mrs. Roy and her two young children left the Nothing Man and sheltered in the cottage that had belonged to Roy’s maternal grandfather. Her grandmother and uncle arrived a few months later to evict the three under the banner of the Travancore Christian Succession Act, the state law that governed, at the time, the rules of property distribution for Christians in Kerala. The act entitled daughters to one-fourth of the estate or 5,000 rupees (approximately $57 in today’s currency), whichever amounted to less. It took years, but Mrs. Roy challenged the act in court and won equal rights for inheritance, branding her as an influential feminist in India’s history book.

In the meantime, however, she was cast out, divorced, and totally broke, carrying an “invisible begging bowl.” After being terrorized by the patriarchal laws that subjugated women, Mrs. Roy became a fearless warrior who championed women’s rights. She empathized with those who suffered and were oppressed. At school, she dressed Roy, then 11 years old, as a Vietcong girl for a school debate. She educated her about the ongoing Vietnam War, the devastation of the landscape by Agent Orange; she told her how the jungles, rivers, rice fields, and communists there were just like Kerala’s, and that what Americans called the Vietnamese, gooks, were what they were, too. Roy practiced her enraged speech denigrating counterrevolutionaries and American imperialists while her voice shook. Childhood—as does the history that precedes you—encodes a brain, body, and spirit. Last year, Roy took the stage in London to accept the PEN Pinter Prize and speak against “unflinching and ongoing televised genocide in Gaza.” She refused to condemn Hamas or Palestinians for celebrating Hamas’s attack on Israel: “I do not tell oppressed people how to resist their oppression or who their allies should be.” Her 11-year-old self, dressed in Vietcong gear, was there, too, speaking. So was Mrs. Roy.

This identification with derogation unfurls backward in time, pinging the invisible begging bowl and brass vase, marking Roy for the future. She leaves home, goes to architecture school, stars as a young tribal woman in a film about the dangers of aligning too closely with colonial rule, doesn’t speak to Mrs. Roy for seven years, becomes an off-grid drifter, writes screenplays and falls in love with her filmmaker collaborator, gets an abortion without general anesthesia because only a man or her mother could sign the form permitting it, publishes her bestselling debut novel and earns enough money to set up a trust to give a portion of the royalties away to progressive causes, writes political essays criticizing development and corporate power destroying Indigenous communities and land, faces sedition charges, spends a day in jail for being in contempt of court, and becomes a self-professed hooligan by way of outspoken critique in the country she finds herself in opposition to for its economic and social policies and treatment of marginalized communities.

Leaving home, writing into existence a life of her own, Roy begins to transmute her childhood role of being Mrs. Roy’s organ to breathe for her, to relieve her of suffering, and save her from death. A process of replacing the organ that serves another with her own desire. Perhaps this is called selfhood. But what makes a self cannot be parsed from the history it is made of.

Roy leaves the filmmaker and buys an apartment of her own in Delhi on a street that she used to bike down as an architecture student. From the balcony, she imagines waving to her younger self passing below. The past is always alive, always there to meet you. There, she begins writing her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Where does fiction come from? Roy poses this question early in her memoir, after recalling a scene from The God of Small Things where the protagonist twins, Esthappen and Rahel, are pushed in a volley of rejection from their mother to father, neither of whom wants to take their children. Roy believed the scene to be a work of fiction, but Mrs. Roy corrected the record after reading the novel. It had actually happened. Memory protects, yet it persists: Roy had repressed this event from her childhood, but it emerged from her unconscious through the act of writing. How can one cope with trauma? Believe it is fiction and write it as such. Trauma insists on finding expression.

These days, Roy is “a well-known and now-wealthy writer in a country of very poor people, most of whom do not or cannot read books.” In that context, “What was the meaning of being me?” she asks in Mother Mary Comes to Me. Indeed, what does it mean to inhabit one’s own subjectivity and position in the particular context of their world? Inheritances, of property and darkness alike, must be reckoned with.

With every book, every essay, every speech, Roy builds worlds that are revolutionary, made from the darkness that she spins into purpose.

Stories are another thing we inherit, whether their origins are personal, historical, or cultural. Roy considers the Malayalam films she grew up watching, where heroines were often raped: They convinced her all women were destined for the same fate. Stories can be used to instill fear and control and set our expectations for what we deserve. On a drive through a national park in her thirties, Roy passes a man lying on his back atop a buffalo cart with a lantern tied to it, singing under the stars, perfectly assured that the animal would take him home. The sight evokes both wonder and jealousy in Roy, for a woman in India would never feel so safe and carefree on a lonely highway. But writers have the ability to tell stories that create the world we want to live in. In The God of Small Things, different castes transgress predetermined borders. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness protests on the behalf of Kashmiri independence. With every book, every essay, every speech, Roy builds worlds that are revolutionary, made from the darkness that she spins into purpose. She may never lie on her back in a buffalo cart singing to the stars, entrusting her safety to the world around her, but she can write about another world that offers the same freedoms to women, men, and to hijras alike.

Revolution, however, is molecular. It is not only political; it also happens within. After Mrs. Roy died, the home she had built was in disrepair. Roy restored it, replacing rusted steel inside filler slab, replacing doors and window frames, ripping out floors and replacing them, replacing wiring and pipes. She likens the process to the Ship of Theseus. If every part of a house is replaced, is it the same house or a different one? I cannot help but understand Roy’s years studying architecture as training for her to later rebuild her mother’s house, plank by plank, especially since this seems to be the only house that she’s ever built. If a daughter begins as a little girl who was her mother’s organ and remakes herself bit by bit to become her own person, is she still the same person or a different one?

The post For Arundhati Roy, Art and Politics Emerged from Her Mother’s Shadow appeared first on New Republic.