The most famous cover in the history of The New Yorker magazine may be for the March 29, 1976 issue, a drawing known as “View of the World from 9th Avenue.” You’ve no doubt seen it: 9th Avenue large and expansive in the foreground, with 10th Avenue and the Hudson River distinguishable in the distance. The rest of the country vanishes into nothingness, a few clumps representing vague notions of “what’s out there” to the west – Texas, Nebraska, Los Angeles. In the far distance lies the Pacific Ocean, and beyond that, featureless protuberances labeled Japan, Russia and China.

Saul Steinberg’s artwork captured the insularity of Manhattan, the blithe sense of locals that not much beyond the island really exists nor matters. The magazine itself has contributed to the mystique of New York as a paragon of sophistication by publishing the most astute cultural and political observers, the finest essayists, the most gifted writers of fiction, and the funniest humorists – James Thurber, Steve Martin, Andy Borowitz, Roz Chast and her fellow cartoonists. And it’s been doing it for a century now.

The magazine gets a fitting birthday celebration in the form of the documentary The New Yorker at 100, directed by Oscar winner Marshall Curry and executive produced by Judd Apatow. The film premiered at the Telluride Film Festival this weekend and will bow on Netflix later in the year.

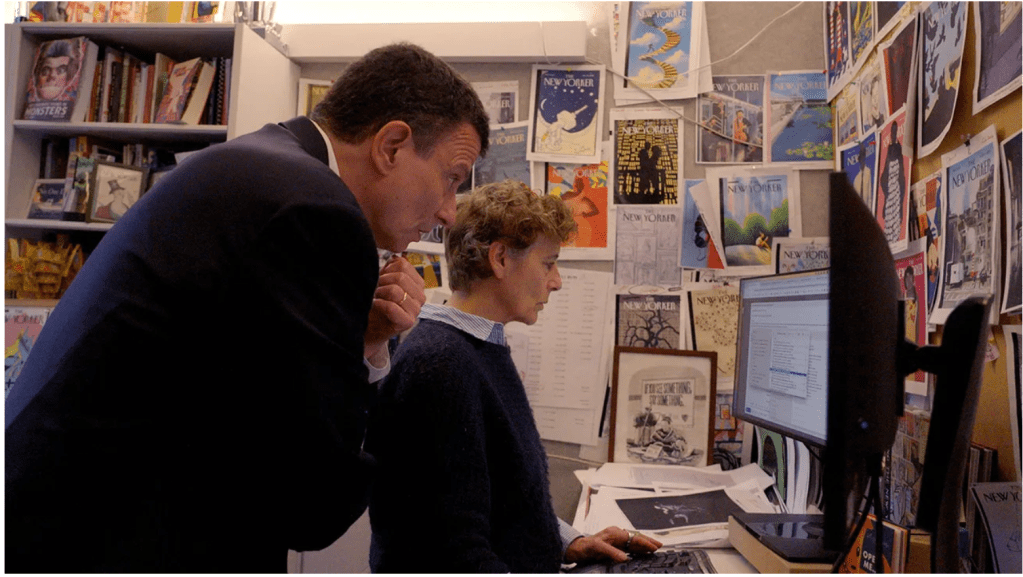

Curry (Street Fight, A Night at the Garden, The Neighbor’s Window) takes us behind the scenes and into editorial meetings presided over by David Remnick, who has run the magazine since 1998. We also meet art editor Françoise Mouly, creative director Nick Blechman, cartoon editor Emma Allen, and Bruce Diones, office manager at The New Yorker for the last 47 years. Celebrity fans testify to their affection for the magazine, including Sarah Jessica Parker, Jon Hamm, Molly Ringwald, The Daily Show’s Ronny Chieng, and Nate Bargatze. I wouldn’t say there are many startling revelations in that footage other than that Remnick seems like a very even keeled and genial guy to work for. He gives hugs to correspondents who drop by his office (Pulitzer Prize winner Ronan Farrow among them), and he never seems flustered by deadline pressure. If any tea has been spilled, it’s been Bisselled out of the carpet before Curry’s cameras rolled.

Most absorbing for me were the archival sections of the film exploring the origins of the magazine and some of the extraordinary work it has published across the decades. Four monumental pieces get special attention in Curry’s film, the first of them John Hersey’s article on the victims of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the U.S., a devastating account which took up almost the entirety of the August 23, 1946 issue.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in three parts in the magazine in 1962 and later as a book, alerted the country to the devastation of the pesticide DDT and is credited with launching the modern environmental movement. Published that same year was James Baldwin’s stunning Letter From a Region in My Mind. Sample line: “Whatever white people do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves.”

The New Yorker famously published Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood in 1966 in four-part serialization, inaugurating a new literary genre the writer dubbed the “non-fiction novel.” Subsequent evidence revealed Capote inserted a bit more fiction into his non-fiction account of the murder of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas than he had initially let on. We learn in the documentary that William Shawn, who succeeded Ross as editor after the latter’s death, came to regret publishing In Cold Blood.

Be that as it may, I would point to other brilliant Capote pieces published by The New Yorker, like 1957’s “The Duke in His Domain,” a withering portrait of the young and hot “Marlon Brandon, on location” making the film Sayonara in Kyoto, Japan. The Muses Are Heard, a hilarious and scintillating piece from 1956, followed the American cast of Porgy and Bess, as well as assorted producers and publicists, as they headed by train from West Berlin to Moscow for a rare performance behind the Iron Curtain.

(I can’t resist mentioning other New Yorker pieces I have treasured: “Crisis in the Hot Zone,” a riveting October 18, 1992 article by Richard Preston that offered “Lessons from an outbreak of Ebola”; every film review written by critic Pauline Kael; the warm, wry prose of Roger Angell; the posthumously published excerpt of an uncompleted novel by David Foster Wallace, my high school classmate from Urbana, IL. Of writers on staff today, I eagerly read every piece written by Susan Glasser, the sharpest observer of Trump and his administration).

It doesn’t take a genius to detect that most of The New Yorker writers in an earlier era were white, as are many today. Curry speaks with some of the sans couleur staffers, and some of the exceptions like Hilton Als, Kelefa Sanneh, Dhruv Khullar, M.D., writers of color who subtly convey that at some point the magazine began to represent more diverse viewpoints than at its origins. It would have been helpful to get a more explicit account of how and when The New Yorker embraced that commitment.

We get an accounting of how Tina Brown took over the editorship of the magazine in 1992, several years after it was purchased by S.I. Newhouse, CEO of Condé Nast. The film recounts how the young editor fired more than 70 staffers and hired Richard Avedon as the magazine’s first staff photography, dramatically elevating the importance of visual content to a publication historically wedded to the printed word and the printed word only. She also hired Remnick, who would succeed her as editor after Brown made the ill-advised decision to link arms with Harvey Weinstein to launch Talk magazine (it lasted about three years, or 3 percent of the longevity of The New Yorker).

Brown’s tenure brought the magazine into the modern era, so to speak. But oddly, The New Yorker at 100 doesn’t explore the biggest challenge the magazine has faced in the last 15 years or so – responding to the digital age that sundered so many other once-influential magazines like Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated (which technically still exist, but whatever). The New Yorker of today, by necessity, has essentially become a daily publication. Yes, the physical magazine is printed once a week as it always has been. But to survive, The New Yorker had to transform itself or die. How did it do that? We don’t find out in this film.

That omission aside, Curry’s documentary offers an entertaining and satisfying tour of an institution that more than ever stands as a bulwark against the philistinism, venality, and meanness of Trump and Trumpian culture, which threatens the foundations of our democracy. I remember decades ago a New Yorker TV ad that sought subscribers for the magazine. In tweedy voiceover, it quoted someone (I have searched online but I can’t determine who) that declared The New Yorker “probably the greatest magazine that ever was.” I, for one, agree. And if there’s a better magazine out there, I’d like to read it.

Title: The New Yorker at 100Festival: TellurideDirector: Marshall CurryDistributor: NetflixRunning time: 1 hr 36 min.

The post ‘The New Yorker At 100’ Review: Entertaining If Incomplete Tour Of “The Greatest Magazine That Ever Was” – Telluride Film Festival appeared first on Deadline.