Four years ago, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published a landmark report, “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector,” that proposed a technical blueprint for a global green energy transition by the middle of this century. The report focused on the economic and technological dimensions of this energy transition. It was an admirable effort that calls for careful study.

But the report was also marked by the flaws of its technocratic conception. Crucially, the broader stakes of the global energy transition went ignored. This is a mistake in urgent need of correction. The decarbonization agenda is not simply about reordering markets or industrial policies, but in fact represents the crucible for a new geopolitical order.

The energy transition is likely to become the center of a new eco-ideological Cold War that will reshape global alignments and provoke existential resistance from the fossil-fueled ancien régime. The central axis of this geopolitical struggle will not be the 20th century’s struggle between liberalism and authoritarianism, but a clash over the metabolic basis of modern industrial society.

The IEA’s net-zero emissions scenario articulates a radical imperative: If we are to limit global warming to the 2.0 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) target enshrined a decade ago in the Paris Agreement—a threshold identified by climate scientists, economists, and policymakers as the point where the risk of dangerous and irreversible climate impacts (such as ice sheet collapse, extreme heat, food insecurity, and sea-level rise) rise sharply—then the global energy system must undergo a full-spectrum transformation by midcentury.

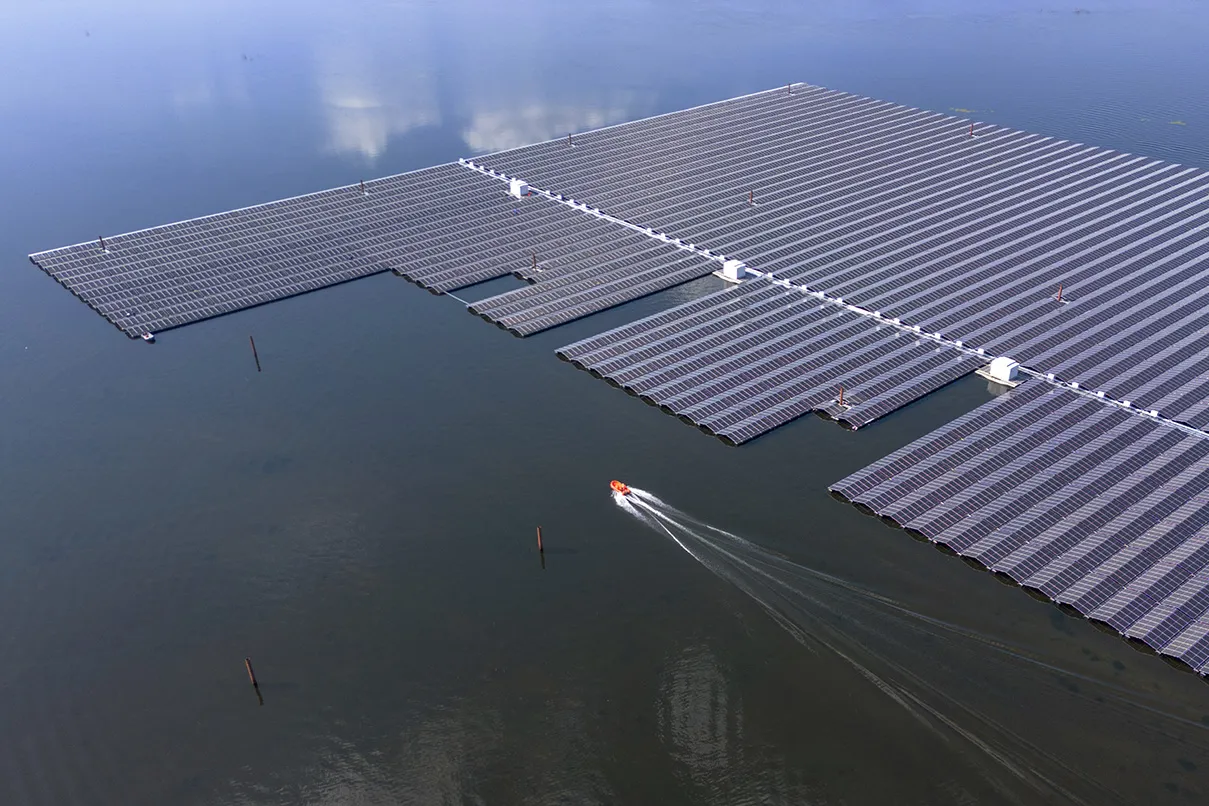

At the center of this transformation is the electrification of everything, powered predominantly by renewables. By 2050, electricity generation must more than double, with 90 percent of it coming from zero-carbon sources—including nearly 70 percent from solar and wind alone. This means building the energy equivalent of the world’s largest solar park every day for a decade.

The transport sector must pivot just as dramatically. Electric vehicles will need to leap from comprising 20 percent of global car sales in 2024 to more than 60 percent by 2030, with all new internal combustion engine sales ending by 2035. The industrial sector, a formidable emitter, must be overhauled with a 95 percent reduction in emissions by 2050—even as AI is rapidly accelerating global demand for electricity. Buildings, too, will require transformation. By 2050, more than 85 percent of buildings must be “zero-carbon-ready,” with half of the global building stock retrofitted to meet new standards.

Underlying all of this is the imperative of a managed decline in fossil fuels. No new oil and gas fields. No new coal mines. Coal consumption must fall by 90 percent, oil by 75 percent, and gas by more than half.

A transformation of this scale and scope will be without historical precedent—with one possible and crucial exception: what China has achieved economically over the past half-century.

In 1978, China was still a largely agrarian society, staggering under the economic consequences of the Maoist era. Per capita GDP was less than $200, and more than 80 percent of the population lived in rural poverty. But in the decades since former leader Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, the country has undergone the most rapid industrialization and urbanization process in human history. Sustained average double-digit GDP growth rates for nearly 30 years transformed China from an economic backwater into the global manufacturing powerhouse. Along the way, it lifted close to 800 million people out of extreme poverty—an achievement that accounts for roughly three-quarters of global poverty reduction in that period.

This transformation did not occur incrementally or organically. It was centrally orchestrated and ruthlessly executed by a one-party state capable of mobilizing resources at immense scale, without the procedural friction or political gridlock common to liberal democracies. Urban master plans were imposed with little regard for local opposition; entire sectors were retooled by fiat; land and labor were redirected en masse to serve national development priorities.

The Chinese Communist Party’s tight control over the state apparatus enabled it to pursue long-term economic strategies insulated from electoral cycles or public referendums. In short, China’s miracle was not just economic—it was also deeply political. It was the most successful authoritarian development model that the world has ever seen.

But this unprecedented industrial ascent came at enormous environmental cost. By the early 2000s, China had become the world’s worst polluter by most metrics. Its cities were choked with smog, its rivers ran black with industrial runoff, and its citizens suffered from some of the world’s highest rates of respiratory illness and environmental disease. In 2007, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide. Its economic miracle had come to look increasingly like an ecological catastrophe.

Yet it is precisely out of this crisis that China’s green transformation was born. Indeed, while the IEA focuses on the “how” of the energy transition, it is equally crucial to understand the “who” and the “why.” Because the central geopolitical fact of the effort to decarbonize is that China has positioned itself to dominate this emergent post-carbon system under the sign of what must be recognized as green authoritarianism.

Beginning in the late 2000s and accelerating dramatically after President Xi Jinping’s ascent in 2012, the Chinese government began to view environmental degradation not just as a public health issue, but also as a threat to regime legitimacy and long-term economic stability. Smog protests in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, especially among the rising middle class, alarmed the Communist Party. At the same time, the party recognized that the industries of the future would be low-carbon and resource-efficient—and that global leadership in green technologies could translate into a new form of geopolitical leverage.

China’s pivot to green tech has been anything but hesitant. It has involved massive investments in renewable energy, electric vehicles, battery technologies, and the mineral supply chains that feed them. Today, China dominates every link in the green industrial value chain. It produces more than 80 percent of the world’s solar panels and more than 70 percent of lithium-ion batteries, and it controls the majority of global processing for key minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

Moreover, China’s green transition is not limited to the export sector. Domestically, the country is now home to the world’s largest fleet of electric vehicles and the most extensive high-speed rail network. It leads the world in electric bus deployment and has pledged to peak its carbon emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. These targets, while ambitious, are backed by real planning infrastructure and a proven capacity for large-scale execution. In 2023 alone, China installed more solar energy capacity than the rest of the world combined did the year before. In wind power, electric buses, and high-speed rail, it has no rival.

How did all this happen so fast?

The answer lies in the structure of China’s political economy. Beijing’s combination of technocratic ambition and unapologetic top-down governance enables it to bypass the procedural frictions that hamper democracies: NIMBYism, regulatory fragmentation, and political short-termism. The country’s “Made in China 2025” strategy, a 10-year plan unveiled in 2015, explicitly identified new energy vehicles and advanced green technologies as key pillars of national development.

In support of these goals, the state deployed a full suite of instruments: generous subsidies, targeted financing through state-owned banks, favorable land-use policies, and domestic content requirements. In many cases, the government created entire economic ecosystems—clusters of suppliers, research institutions, and manufacturers—to support the scaling of key green industries.

Equally important was China’s ability to rapidly scale up production. Once a strategic decision is made at the top, implementation cascades through its bureaucracy with remarkable speed. In the solar industry, for instance, what began as a state-led initiative to reduce urban air pollution quickly became a globally competitive export juggernaut. Between 2010 and 2020, China drove down the cost of solar photovoltaic panels by more than 80 percent, flooding global markets and undercutting Western producers—many of which went bankrupt. Today, even countries wary of Chinese political influence are structurally dependent on Chinese green tech.

Some of this has been achieved through what the West sees as unfair practices: forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, and subsidized dumping. But regardless of the methods, the result is clear: Over the past two decades, China has leapfrogged from the world’s greatest environmental villain to its green-tech hegemon. It did not do so by becoming more democratic or market-driven—but rather by leveraging the unique advantages of its authoritarian developmental state.

To be clear, contradictions remain. China continues to build coal-fired power plants, particularly to ensure grid reliability and support heavy industry. Its Belt and Road Initiative has financed fossil fuel infrastructure in developing countries, even as it touts its green leadership. But these tensions do not negate the fundamental direction of travel: China’s centrally coordinated industrial strategy, long-term planning horizon, and unrivaled production capacity have enabled it to capture the commanding heights of the global green economy.

This dominance is not merely economic. It confers geopolitical power. Just as OPEC’s control over oil gave it leverage in the 20th century, China’s grip on the green energy supply chain gives it enormous influence in the 21st.

It is on this basis that I’ve previously proposed the possibility of an emergent Sino-European “green entente.” While the European Union and China are far apart on cultural and political issues concerning human rights, they share “metabolic interests” that make this sort of alignment plausible. Not only are China and the EU currently the two biggest oil importers on the planet, but for exactly that reason have also both become the fastest developers and deployers of renewable energy technologies.

These material facts have geostrategic implications: Europe, having already suffered the consequences of its reliance on Russian gas, now confronts the unsettling prospect of long-term dependence on natural gas from an increasingly hostile United States—giving it a strong strategic incentive to seek energy autonomy. At the same time, China’s unchallenged leadership in solar, wind, and battery production provides a compelling foundation for a formalized Sino-European supply chain partnership, ensuring Europe’s access to vital technologies and raw materials.

The convergence, if it happens, will not be ideological, but pragmatic: Europe will provide affluent markets and a stable political commitment to greenery while China will supply the industrial muscle. Though incongruous from the point of view of the democracy-versus-autocracy ideological divisions of the 20th century, a Sino-European geo-ecological condominium makes much more sense if we recognize that the central geopolitical debate of the 21st century is not over which governance model offers the best route to economic prosperity and political recognition, but rather over how best to address planetary challenges.

And here, for better or worse, there is a strong alternative to the Sino-European vision of a green energy transition.

As the green transition gathers momentum, underpinned by Chinese technological prowess, a reactionary counter-bloc has already begun to coalesce—not around a commitment to liberal democracy or human rights, but to the continued extraction and political centrality of hydrocarbons. Call it the axis of petrostates: a nascent coalition of states—notably, the United States, Russia, and Saudi Arabia—whose economic models, geopolitical power, and civilizational narratives are inextricably tied to fossil fuels.

Each of these countries is responding to the decarbonization agenda not as a technical challenge to be managed, but as an existential threat to be resisted.

At first glance, these countries differ in regime type: The Trumpified United States remains formally democratic (though increasingly authoritarian), while Russia is a post-Soviet autocracy, and Saudi Arabia is a near-absolute monarchy. Though all are authoritarian, what unites them is not political form, but a shared vision of national sovereignty that subordinates environmental constraints to national identity, economic primacy, and civilizational pride. Each rejects the premise that climate imperatives should dictate economic or political reordering. In their shared rejection of the green transition, they are forming not merely an economic alignment, but also a reactionary ideological bloc—one rooted in ethnonationalism, energy dominance, and revanchist nostalgia.

A year ago, the inclusion of the United States in this axis might have seemed counterintuitive. After all, under the Biden administration, the United States had pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and passed the Inflation Reduction Act, the most ambitious climate legislation in U.S. history. But underneath this policy veneer lay a structural contradiction: The United States is the world’s largest oil and gas producer, and maintaining the stability of global fossil fuel extraction is now (as it has long been) a critical pillar of its geopolitical strategy.

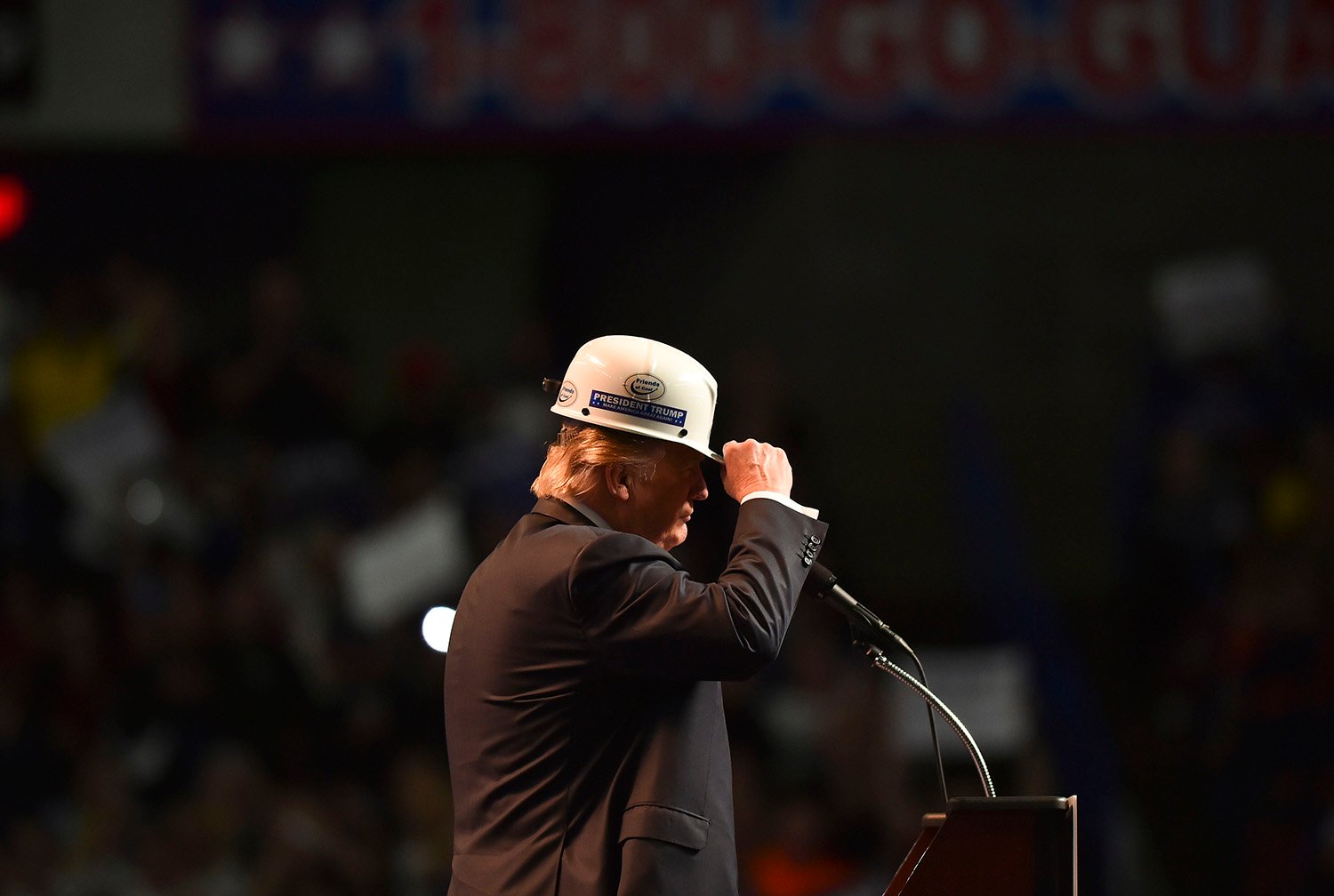

With that said, the second election of President Donald Trump last year does represent a sea change. While Republican-led states have long resisted federal renewable energy mandates, and right-wing media outlets have framed decarbonization as a globalist assault on national sovereignty and working-class livelihoods, the second Trump regime has made what were long political talking points into the center of an overtly anti-renewables energy policy. If the United States in the first quarter of this century promoted a broadly bipartisan “all of the above” energy policy (with the exception of nuclear energy), the new regime it is taking a stridently “fossil fuel-or bust” line.

Beneath this resistance lies a deeper ideological formation: a petro-populist vision of the United States as a land of rugged independence, boundless energy, and divine entitlement to carbon-intensive modernity. This version of American identity is aggressively defended by fossil fuel lobbies, right-wing think tanks, and a political base mobilized by anti-elite grievance. While members of the national security elite have emphasized the need for vast new amounts of electrical production in order to be able to develop new AI models that can compete with Chinese models, so far this has not moved the energy policy of the Trump regime.

From this perspective, the Trump regime’s rejection of climate commitments represents the consolidation of a petro-nationalist political economy in which fossil fuels become both the material basis of power and a symbolic bulwark against “cosmopolitan” or “globalist” green governance. As so often with the Trump regime, a trolling line like “rolling coal” has gone from culture war meme to hard-nosed policy.

It is in this context that the Trump regime’s formation of a petrostate axis with Russia and Riyadh makes as much practical as ideological sense.

For Russia, hydrocarbons are not just an economic lifeline but also the foundation of its ongoing geopolitical relevance and civilizational self-conception. Oil and gas revenues fund the Kremlin’s domestic patronage networks and foreign adventures. Energy exports give Moscow leverage over Europe and political influence across the global south. In Russian President Vladimir Putin’s revanchist narrative, fossil fuels are entwined with Russia’s imperial legacy—a source of national pride and global stature.

The green transition, in this context, threatens to strand Russian assets, hollow out its governmental budget, and marginalize it from emerging technological value chains. From this point of view, working with the Trump regime to slow or stop the global green energy transition is simply a matter of shared national interests.

Like Russia, Saudi Arabia depends on fossil exports for national survival. Despite talk of “Vision 2030” and investments in renewables, the kingdom continues to double down on oil, aiming to increase production capacity and capture market share as other producers (theoretically) phase out. Its ambition is not to phase out fossil fuels, but to monopolize them as global supply tightens. Saudi oil is among the cheapest and least carbon-intensive to produce, and the country maintains the most extra production capacity—making it the inevitable swing producer (and thus power player) in a world where some level of fossil fuel use persists.

The House of Saud uses its oil rents to finance both its domestic social order and its international influence. Saudi Arabia’s version of petro-authoritarianism is rooted in a dynastic, patrimonial state that fuses nationalism and oil wealth into a coherent ideological formation that has sidelined formerly powerful religious authorities. Like Russia and the United States, Riyadh views climate governance not as global stewardship, but as an encroachment on its sovereign prerogatives. As with Russia, the Saudi regime regards the prospect of a green energy transition as an existential threat. Unsurprisingly, the kingdom has used its position in OPEC+ and international climate forums to obstruct ambitious targets and undermine fossil phaseout language.

Though the Trump, Putin, and Saud regimes are all authoritarian, what ties them together is not a shared governance model, much less an ideological conviction that this model should be generalized to other countries, but an underlying interest in the domestic and international power that each of them derives from fossil sovereignty. They want other states to remain fossil fuel-dependent because that dependency translates to geopolitical leverage for them. Their strategy is rooted in a revanchist yearning to restore past greatness through fossil-fueled nationalism.

These regimes will seek allies among other carbon-intensive economies, fostering counter-networks that resist the new green order. In this geopolitical configuration, fossil fuels become not just commodities, but symbols of cultural autonomy and political defiance.

For these states, the IEA’s vision of a net-zero world, perhaps under Sino-European leadership, represents political and economic warfare. Their likely response will not be passive decline but active resistance, potentially escalating to kinetic conflict. One can expect them to weaponize energy markets, foment instability in resource-rich regions, conduct cyberattacks on green infrastructure, and amplify climate disinformation. Their ideological counternarrative will not only denigrate green tech, but will also cynically conflate decarbonization with neocolonialism, painting the green transition as a Chinese imposition designed to entrench global hierarchies and erode national sovereignty.

Of course there will also be tensions within each bloc. During the original Cold War, there were famous tensions within both camps. On the Communist side of the Iron Curtain, there was the rivalry between Yugoslavia’s Josip Tito and the Soviet Union’s Josef Stalin from 1948 on, and even more famously, the Sino-Soviet split, which led to actual border skirmishes between China and the Soviet Union in 1969. On the other side, there were also many tensions between the United States and its allies, with French President Charles de Gaulle for example famously removing France from NATO’s integrated military command in 1966 primarily to assert French independence and sovereignty on the world stage. The same will no doubt be true in the new eco-ideological order: the Sino-European entente will certainly not be without its internal tensions, just as Russian-U.S. geopolitical rivalry will continue despite their metabolic alignment.

As with the original Cold War, a big question will be how the global south aligns. The decision on which side to pick in the new cold war won’t be merely about ideas, but about the whole infrastructural model for a country, including the computing infrastructure. Choosing to go with the Sino-European entente will mean that a country probably will also have to commit to building its computing infrastructure on the China stack—which, depending on what the United States does with its own infrastructural assets, could be an opportunity or a liability.

This vision of an eco-metabolic division of the world is at odds with the alternative view, proposed by lingering nostalgists for the liberal international order, of an Iran-China-North Korea-Russia axis versus a still-unified alliance of “western democracies.” But the alliance of democracies is already dead, slaughtered by Donald Trump’s triumphant return to power. In this emerging post-liberal geopolitical order, the world is not dividing along the lines of democracy versus autocracy; the axis of petrostates and the Chinese model both include unapologetically authoritarian members. Rather, the division is between those who see ecological modernization as a biogeochemical imperative for sustaining planetary habitability, and those who see decarbonization as a threat to their so-called way of life.

In this new Cold War, the battle is not just over emissions, energy markets, trading systems, and technology. Nor is it just about sovereignty or identity. Rather, it is about the metabolic basis of modern civilization in a warming world. This reshuffling of alliances is ultimately about competing visions and narratives of modernity, over what it takes to modernize, to survive, and to flourish. Will the future be forward-looking, green and bravely planetary—or will it be backward-looking, carbon-intensive and stridently sovereigntist?

The post The Coming Ecological Cold War appeared first on Foreign Policy.