From the outset, one inescapable reality of U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term has been its frenetic busyness. For those who support it, the sheer pace of Trump’s agenda has been a hallmark of its success.

For others, though, Trump’s rapid-fire proclamations, orders, and initiatives in pursuit of an increasingly radical economic and political agenda present a fundamental and unfamiliar challenge: No sooner than Trump dominates the news with one topic, he launches into another, routinely leaving his critics breathless.

To wit, think of Trump’s utterly improvised and fruitless summitry with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska, his attack on the Smithsonian Institution for its alleged focus on slavery, the rolling federal takeover of policing in Washington, and the Pentagon’s recent firing of the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency after it raised doubts about the impact of the U.S. attack on Iran’s nuclear sites in June.

Think of Trump’s push for Texas and other Republican-led states to gerrymander their electoral maps, his weaponization of the attorney general’s office (as seen in the release of the transcripts of the interview between Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, his former personal attorney, and Ghislaine Maxwell about the Jeffrey Epstein case), and the FBI search of the home and office of Trump’s former national security advisor, John Bolton.

All of these developments have occurred in little more than a week. Taken separately, each of these is worthy of deep national discussion, but the former reality television star’s approach to power seems strategically designed to prevent this, thus allowing him to plow ever forward.

Yet I am not as surprised by their failure to generate debate as I am about that of another matter entirely: Trump’s attack on the foundations of the U.S. economic system, which had gone largely unchallenged for around 80 years. One might have expected stout opposition to this, or at least loud calls for clarity on the rationale behind these moves—not just from Trump’s customary critics among centrists and the left, but also from traditional conservatives, big business, and the monied class more generally.

Each week seems to bring news of a substantial, if never clearly articulated, repudiation of the U.S. government’s commitment to what Americans generally call free-market capitalism. This label has always been something of an exaggeration, but it nonetheless captures a salient feature of the country’s political economy in the postwar era: Government during this time, especially under Republican administrations, has promoted the idea that private enterprise is responsible for producing wealth in the United States, while the role of the state is to create a stable policy environment—one promoted by transparent and independent institutions, and not based on the political whims of the executive branch.

Trump’s assault on this setup began with his campaign against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, and by extension, that traditionally independent institution itself. The president has recently nominated a partisan to the bank’s board and attempted to oust another member, Lisa Cook, on what seems to be a transparently political basis, claiming that she engaged in mortgage fraud.

Last week, after weeks of unrelenting personal attacks by Trump and pressure to lower interest rates, Powell signaled that he will likely grant the president’s wish in September. The stock market leapt in response, but plenty of analysts warned that Trump’s interference in the interest rate-setting process augurs poorly for the U.S. economy.

Recent actions by Trump have attacked even more basic precepts of free-market capitalism in the United States. The first of these has been his chaotic imposition of high tariffs on a host of countries to levels not seen since the prewar era. His administration has carried this out while continuing to pretend that other countries—and not U.S. businesses and domestic consumers—will pay for the tariffs. All the while, Washington has not been transparent about how it will use the proceeds from these levies.

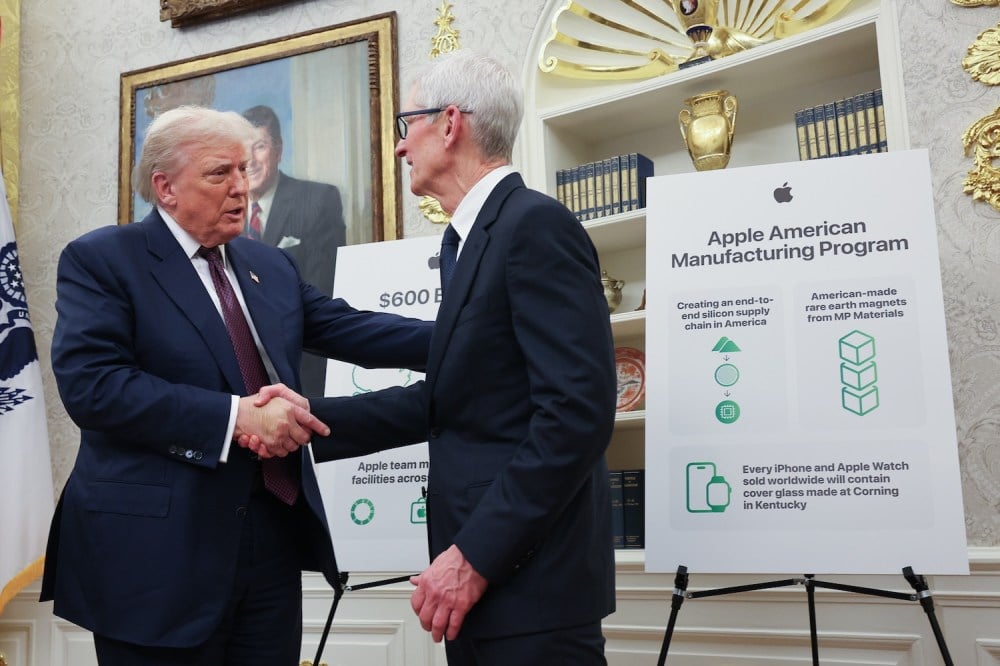

Then, Trump announced last week that the U.S. government will acquire roughly 10 percent ownership in Intel, a former leader in microchips that has struggled badly to keep up with the competition. This came soon after what briefly appeared like it might be a one-off arrangement, however unusual, when Trump required two of the country’s leading microchip manufacturers—Nvidia and AMD—to yield 15 percent of their revenue on sales of their strategically sensitive processors to China. Earlier this month, Trump also granted Apple exemption from 100 percent tariffs on chips after the company promised to invest $100 billion on manufacturing in the United States.

It was not long ago that Republican politicians, business leaders, and conservative media outlets such as Fox New were astir over the prospect that Zohran Mamdani, a self-described democratic socialist, could soon be elected mayor of the country’s economic capital, New York City. But the structural implications of Mamdani’s vaguely socialist proposals, such as free bus transportation, shrink in comparison with the scope of Trump’s initiative to change the country’s political economy.

As Washington Post reporter Gerrit De Vynck noted recently, “Some Republicans and Libertarians have complained that Trump’s transactional moves are a betrayal of the GOP’s traditional commitment to free-market policies. … But GOP lawmakers and those in corporate boardrooms or C-suites have largely stayed quiet.” Spokespeople for BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Corporation, Intel’s three largest stockholders, did not return the Post’s requests for comment.

Some of U.S. conservatives’ reluctance to criticize Trump over these radical economic changes is surely due to their fear of provoking the ire of a leader who is quick to seek retribution against perceived critics and opponents. Their reticence may also be due to their general enthusiasm for the tax cuts for the wealthy that Trump has signed into law.

Another problem hindering criticism from this quarter, though, may be just how unusual the situation that Trump has created is—and how difficult it is to put a name on a system that is being cobbled together on the fly, without any clear or coherent policy vision.

Even as Trump would abjure the tag of socialist, some analysts have affixed the label of “state capitalism” to the restructuring underway. There is something to this. Historically, this descriptor has been applied to a wide range of systems, from Nazi Germany to contemporary China and even modern European nations such as France. At a minimum, state capitalism implies the government’s strong strategic participation in the economy and in major industries, along with the state setting firm priorities for future economic growth through policy, regulation, and investment.

Beyond slogans such as “America First,” though, it is hard to see the long-term logic of Trump’s economic interventionism. China is openly pushing its model of state capitalism with a will to dominate what it sees as industries of the future, including electric vehicles, green energy, artificial intelligence, and robotics.

Only time will tell if Beijing has struck on a winning strategy, especially given what economists see as chronic misallocation of capital and overcapacity in many of the industries favored by the Chinese state. What seems clearer, at least early on in Trump’s second term, though, is that his policies favor legacy industries over the promotion of new ones. In one trade negotiation after another, Trump has insisted that other countries purchase more U.S. oil and gas, agricultural products, and armaments, as if these will continue to propel the country’s economy well into the future.

In fact, Trump’s approach to energy issues may provide the best key to understanding his economic policy. He capped off another head-spinning week on Friday by ordering a halt to work on a nearly completed major offshore wind farm that would supply electricity to Connecticut and Rhode Island. Asked to explain why, the best answer that Lee Zeldin, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, could summon during a Fox News interview was: “The president is not a fan of wind.”

What this seems to confirm is that much of the Trump administration’s decision-making is based not on solid economic analysis or considered debate among well-qualified experts, but on his whims. And there is a name for a political system governed this way—it is called personalized rule.

The post Trump’s Economic Policy Is More Radical Than You Think appeared first on Foreign Policy.