Great-power competition forms the overarching framework of international politics today. Uneasy about China’s deepening engagement throughout much of the world, the West—led by the United States—views Beijing as a systemic and strategic competitor that must be opposed, which is not unlike Cold War-era fears over the spread of Soviet influence. Intentions to roll back or counterbalance Chinese ascendancy are now shaping Western strategies toward the global south. Forcing countries to choose has become a popular strategy, but the global south will not give up on China or make binary choices.

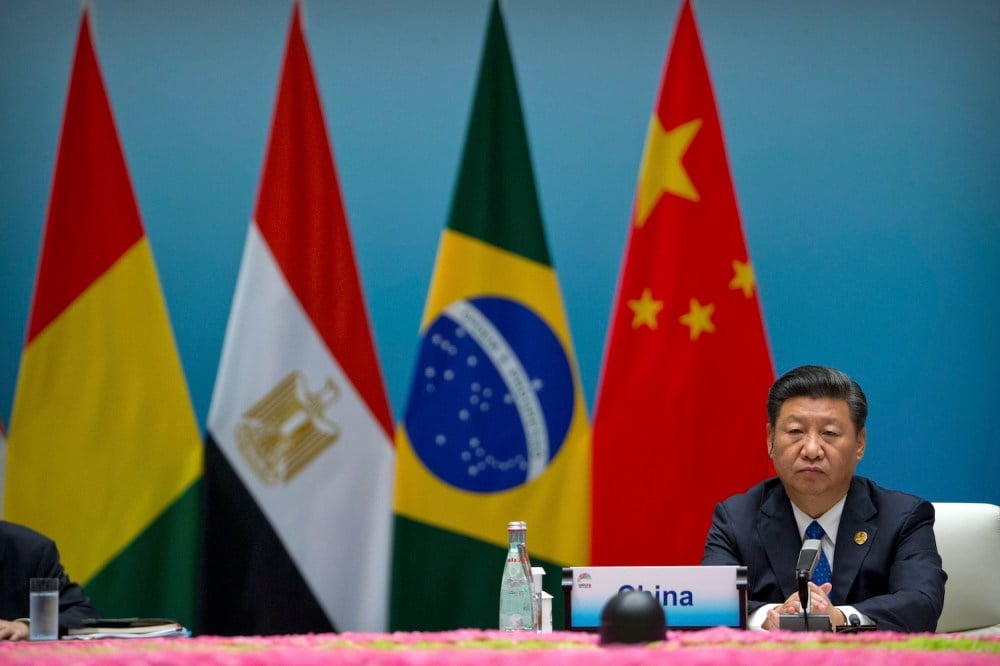

In a recent, stark reflection of this, U.S. President Donald Trump warned on social media that any countries “aligning themselves with the Anti-American policies of BRICS” will face additional tariffs. Celso Amorim, a chief advisor to Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, said that those threats “are reinforcing our relations with the BRICS, because we want to have diversified relations and not depend on any one country.”

In the absence of competing visions of global politics and economic organization that characterized the Cold War, American bullying to curb China’s influence in the non-Western world is likely to backfire. On the contrary, Trump’s unpredictability and disdain for rules and norms, coupled with the West’s waning soft power, boost China’s influence and help its efforts to discursively redefine the global south, of which it is an integral part, as a non- or even an anti-Western bloc.

Countries in the global south tend to be price-takers, and, in a transactional world, China offers more than any other major power. This is particularly true for countries in Southeast Asia, for whom infrastructure remains a work in progress. As an infrastructure superpower, China appeals directly to one of the global south’s key needs. It has spent more than $1.3 trillion on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects in the global south over the past decade, which far exceeds that of its peers’ investments on projects like Europe’s Global Gateway, the United States’ Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union.

That is not to say all of China’s projects run smoothly. In Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Myanmar, Malaysia, Kenya, and Zambia, various issues have arisen, including debt distress and entrapment, inflated costs, relying heavily on Chinese workers, governance problems, security concerns, and domestic opposition. Nonetheless, China has shown agility in adjusting its programs to host countries’ conditions. China is now trying to align the BRI with the African Union’s Agenda 2063, a strategic framework to transform the continent over the next 50 years.

China sees the Trump administration’s retreat from global commitments and soft-power projections as an opportunity to capitalize on. While the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) offices around the world were being closed down this year, China’s BRI-related contracts and investments amounted to $125 billion . Even though China’s BRI investments have become smaller and more targeted, the first half of 2025 saw the highest BRI engagement ever for any six-month period, with Africa and Central Asia seeing the most investments. The United States is also not alone on this front, either. Though not as drastically, its retreat is being matched by the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, which have all cut their aid budgets to shift resources over to defense spending—prioritizing their hard power over soft power.

China itself has limited soft power. People might be interested in its goods, but not as much in the Chinese way of life or cultural products. However, one of China’s main sources of soft power today stems from the United States losing its exceptionalism and appeal.

It’s not surprising, then, that various surveys conducted by the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia and Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute reveal that more Southeast Asians today tie the future of their region’s economy to China than to the United States or Europe.

A similar picture is emerging in the diplomatic sphere. As Trump pursues his “America first” agenda and attacks multilateral institutions and agreements, the global south finds China’s narratives of a “shared future” and “mutual respect” more appealing. China’s long-standing efforts to present itself as a dependable partner have also paid off, and it has established forums for cooperation with Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East.

Capitalizing on the United States’ and the West’s moral and relative material decline, China is redefining the global south’s geopolitical identity as non-Western and positions itself as an integral part of it. At a press conference on March 7, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated, “China is naturally a member of the global south, because we have fought colonialism and hegemonism together in history, and we are committed to the common goal of development and revitalization.” Similarly, at a time when Trump is causing widespread fear and anxiety through his trade wars and imposing tariffs on one country after another, China has announced that it has abolished all tariffs on the 53 African countries that it maintains diplomatic relations with. The announcement that was posted on the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s website is titled “China-Africa Changsha Declaration on Upholding Solidarity and Cooperation of the Global South.”

This narrative has the objective of framing the global south in more geopolitical terms, rather than with the economic focus that was prevalent during the Cold War. It also equates the global south’s geopolitical identity as non-West and counter-hegemonic, implying anti-Westen.

Many in the global south view China as a peer developing country. While the United States sees China’s rise as a threat, many developing countries are inspired by its success and aim to emulate it. Former Indonesian President Joko Widodo once told his cabinet to learn from China’s development strategy. A 2024 survey of people in 35 countries by the Pew Research Center showed a divide in views on China’s impact. Respondents in high-income countries viewed China’s economic impact on their countries more negatively, with Americans being the most negative at 76 percent. Conversely, those in middle-income countries saw it more positively, such as about two-thirds of Malaysians and Nigerians holding a positive outlook.

However, nuance is warranted here. China’s narrative and strategy of constructing the global south as non-West and framing itself as an integral part of it do not mean that their interests are aligned. On numerous occasions, China and the global south are on opposite sides of the table. The case in point was China’s position on the G-20’s Common Framework for debt treatments for low-income countries. As the largest bilateral lender to developing countries, China was unwilling to participate in multilateral debt restructuring unless the World Bank and regional development banks agreed to write down their loans.

At the same time, China’s potential as a peer competitor to the United States further enables multipolarity—which many middle powers and global south actors see as a necessary systemic condition for their global political agency. Many countries in the global south, even those that have military pacts with the West such as India, pursue strategic autonomy through multi-alignment or hedging, viewing a multipolar world as a means to enhance their independence.

Global south countries also worry that clear strategic choices could entangle them in bloc politics, risking further regional fragmentation. This concern is partly shaped by the Cold War, when bipolar blocs led to increased regional polarization and division. Think of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization of 1954 and the 1955 Baghdad Pact in the Middle East (later the Central Treaty Organization after Iraq withdrew in 1959). Like NATO, these blocs aimed to contain Soviet influence and communism, contributing to regional fragmentation. However, most regional countries, even then, rejected the Cold War bipolar logic and refused to join, leaving these organizations with limited local participation.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), in line with its position of not choosing sides, has embraced both the United States and China into a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP). It has also cooperated with China’s BRI as well as the United States’ IPEF.

While the Middle East currently suffers from intra-regional polarization and rivalries like the Israel-Iran conflict and Iran-Gulf states contests, most regional actors are not keen on adding a global layer to their existing regional tensions. The United States remains the top regional security actor, but China is now the largest trade partner, especially for the Gulf. Regional states do not see their U.S. ties as a barrier to deepening relations with China. The United States provides a security umbrella for the Gulf, but Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also have CSP frameworks with China.

At the 2023 G-20 summit in New Delhi, the United States announced the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, a major transregional connectivity project aimed at rivaling the BRI and reducing China’s regional influence. However, regional states see no contradiction in participating in both, believing that involvement in multiple projects reduces dependency on a single country and increases flexibility.

Importantly, though, the global south does not want a China-centric world order to replace the existing one. These countries are concerned that once China ascends to superpower status (if it is not already there), then it would not be immune to hegemony syndrome, which often affects great powers. They also worry about the future of Chinese nationalism—whether, like in the United States, it might develop into an insecure and reactionary form.

China distinguishes itself from the West through its policy of noninterference in the domestic politics of other countries. However, this has yet to be tested in regions of strategic priority for China, such as Southeast and East Asia; once Beijing feels more secure in its superpower status, it may attempt to establish a China-centric unipolar order in Asia despite promoting a multipolar order for the world at large.

Spheres of influence, an outcome of great-power rivalry, are likely to lead to an international security environment that will be more challenging for countries in the global south to navigate. Unlike the Soviet Union, China isn’t exporting a model or ideology. Instead, its combination of an open capitalist economy with a closed authoritarian political system makes it a model for authoritarian regimes both outside and inside the West. It offers an alternative to the Western liberal view on the question of political legitimacy. Instead of democracy and political participation, it promotes development and economic progress as the main paths to political legitimacy.

China’s international narrative differs from that of the United States and previous superpowers such as the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, and the Ottoman Empire, all of which claimed exceptionalism and universalism. Beijing rejects universalism both in political and value terms, despite its official ideology being rooted in Marxism and communism, which have a universal language. Such rejection of universalism paves the way not only for multipolarity, but also for multi-ordering—in line with sphere of influences—in global politics. Whatever its short-term appeal, such abdication of universalism or shared reference points and principles for humanity does not bode well for the global south in the long term.

China has focused on turning itself into a reliable and appealing choice for countries in the global south without forcing them to choose between it and the United States. In contrast, the United States is pressuring them to make a binary choice without genuinely investing in making itself a better choice. For countries in the global south, China’s narrative is more appealing as they believes their interests are better served by an international system that offers multiple choices rather than one that forces them to choose one side or the other.

The post Why the Global South Won’t Give Up on China appeared first on Foreign Policy.