Talk of the U.S. dollar can have a frustratingly abstract, near-mystical quality to it. Even putting aside the crypto crowd’s pseudo-philosophizing about the future of money, when most commentators speak of the dollar as a “reserve currency,” it’s often imprecise and conjures up an image of greenbacks stored in central bank vaults. This, in turn, is meant to provide the United States with far-reaching economic superpowers.

Yet the fate of the dollar is nonetheless an important story to tell, especially these days. After April 2, when U.S. President Donald Trump imposed sweeping tariffs—bringing the U.S. average effective tariff to its highest level in nearly a century—the dollar started behaving strangely. An economic textbook would tell you that U.S. tariff hikes strengthen the dollar: Higher duties decrease U.S. demand for (now higher priced) foreign goods and therefore demand to swap dollars for foreign currencies to pay for those goods. Yet the dollar fell after April 2—it has declined 8 percent thus far this year—and there were periods in April when the dollar fell, bond prices fell, and U.S. equity markets fell, an alarming trifecta mostly seen in emerging markets as a sign of panicked capital flight. What’s going on here?

Into this fog strides Kenneth Rogoff, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with his wonderful new memoir-cum-prognostication Our Dollar, Your Problem. If anything, the book is too narrowly titled. Yes, Rogoff puts analytical meat on the bones of an often maddeningly ethereal debate about the future of the dollar and why it matters. But he also provides a top-bucket world tour of recent economic history and analysis of the major global economies: the United States, European Union, China, and Japan.

The most germane question these days is whether dollar supremacy can last in a world of abrasive and volatile U.S. economic policymaking and as sophisticated rivals such as China and Russia seek to build a parallel financial system insulated from the long arm of U.S. sanctions. Perhaps even more fundamentally, some on the populist right in the United States have begun to question whether the juice of the global dollar is worth the squeeze. Vice President J.D. Vance and others have argued that dollar supremacy has hollowed out U.S. manufacturing by increasing the value of the dollar and therefore the relative price of U.S. exports.

To Rogoff, dollar dominance is more than worth it in light of its many benefits: from driving down U.S. interest rates and spurring investment and economic growth to foaming the runway for greater U.S. borrowing during crisis to arming the United States with powerful financial sanctions.

Yet he also believes that the relative decline of the dollar is near inevitable, even if it will remain the most important international currency. The pace of that decline, however, is an open question. The biggest accelerants would be a bout of rampant U.S. inflation, a fiscal crisis brought on by the runaway train of U.S. debt, or an erosion of the independence of the U.S. Federal Reserve. In short, the future of the global dollar mostly depends on economic sanity prevailing in Washington, rather than machinations in Beijing or other foreign capitals.

To call the dollar the global “reserve currency” is a somewhat narrow and outdated shorthand. Under the Bretton Woods system established in 1944, the dollar did act quite literally as the world’s reserve currency: To stabilize global prices, Bretton Woods pegged each of the world’s currencies to the dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold at $35 per ounce. Foreign central banks needed to hold enough dollars in reserve to back their own currencies, and the United States had to hold enough gold to back the promise of convertibility.

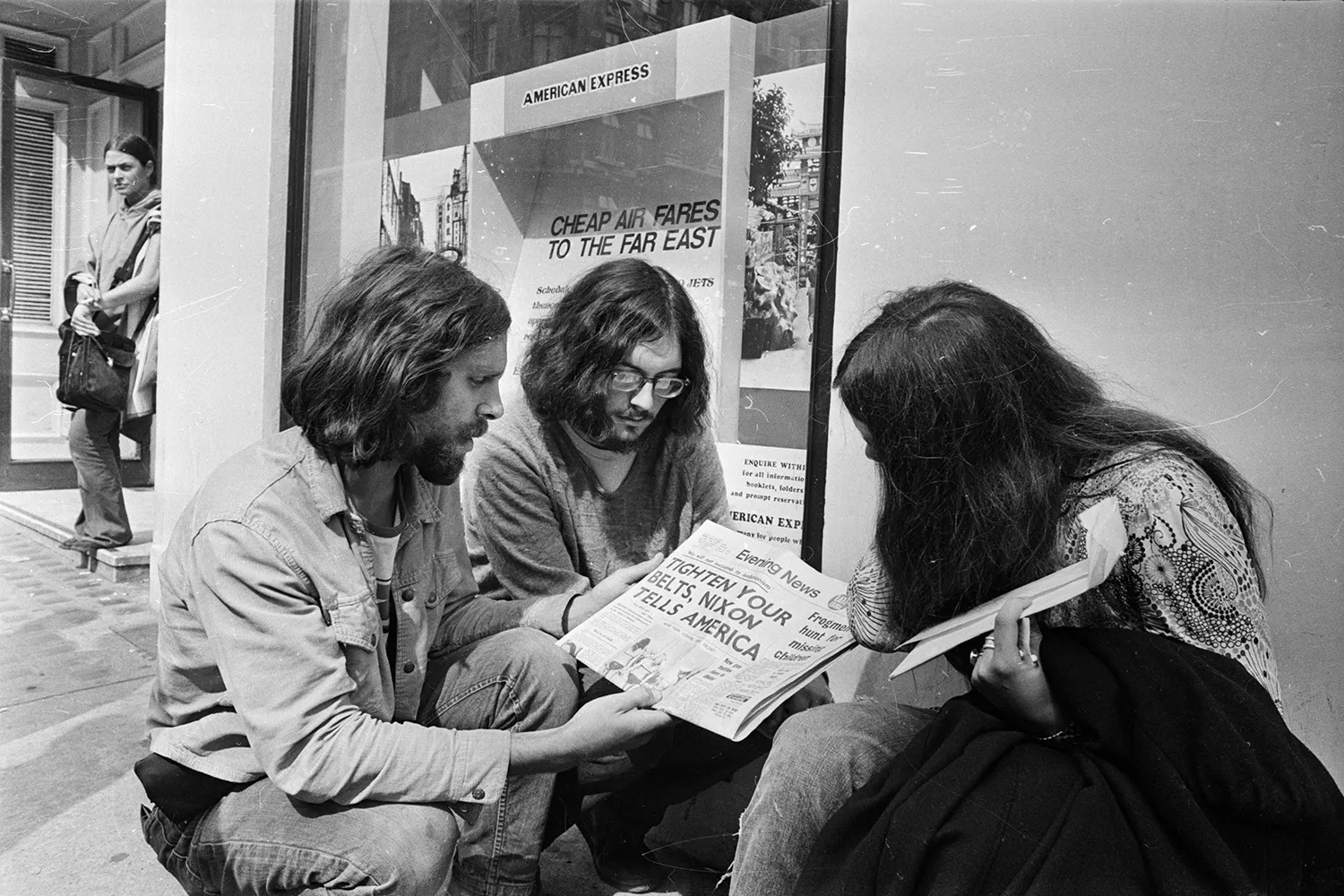

This all came to an abrupt end in 1971, when President Nixon crashed the United States out of the Bretton Woods system, ending dollar convertibility to gold. But the now free-floating dollar has remained the undisputed king of the international monetary system. As Rogoff points out, more than 60 percent of countries use the dollar as a reference currency for anchoring their exchange rates. Today, the dollar still accounts for 59 percent of foreign exchange reserves, though that number has dwindled from more than 70 percent in 2000.

But central bank reserves and currency pegs tell only a small part of the story. The dollar also serves as the lifeblood of international finance. Former Wall Street Journal reporter Paul Blustein paints this picture with clarity and precision in his excellent new book, King Dollar. The greenback acts as a wholly unrivaled vehicle currency—a financial lingua franca used to settle international transactions.

There’s a simple reason for this: Liquidity is lacking across every foreign currency pair. So, if a Japanese company wants to import Brazilian goods, its bank first converts yen to dollars, which is then converted to Brazilian reals to pay the exporter. This is why nearly 54 percent of global exports (more than 75 percent outside Europe) are invoiced in dollars and 88 percent of foreign exchange transactions include the dollar. What’s more, these cross-border transactions are nearly all transmitted and cleared through correspondent bank branches located in New York. Blustein notes that more than 90 percent of large-value, cross-border transactions in dollars are ultimately routed through the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) in midtown Manhattan.

To enable this important role as the financial lingua franca, the dollar possesses the essential qualities of a vehicle currency: a stable store of value and deep liquidity (with about $5 trillion currency swaps and $1 trillion in U.S. Treasurys traded daily). Moreover, there’s an intuitive network effect of banks all using the same language.

When you think about the supremacy of the dollar in this way, its position becomes a lot more unassailable. Recent threats from the BRICS grouping of countries, for example, to create its own currency dissolve into puffery. And what’s the alternative? The yen is tied to an economy representing 3.8 percent of global GDP and falling, the euro faced a near-existential debt crisis in the 2010s, and the Chinese renminbi suffers from strict capital controls.

Economists are fond of using “exorbitant privilege” to describe the benefits of dollar dominance, a highfalutin phrase coined by French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1965. But what does this mean in practice? Rogoff pores over the academic literature and calculates that demand for the greenback as a financial vehicle drives down U.S. interest rates by at least 0.5 percent, decreasing the cost of everything, from U.S. government debt to consumer and business borrowing. Half a percent may seem like a small number, but that’s $185 billion a year on $37 trillion of U.S. government debt and $2,500 a year on a $500,000 mortgage. These lower financing costs, as well as Washington’s enhanced ability to borrow in times of crisis, may be worth almost 1 percent of GDP.

The centrality of the dollar also arms Washington with devastating sanctions weaponry. Cut off access to the dollar and CHIPS, and foreign banks are almost entirely cut off from the international financial system. This story is most definitively told in Edward Fishman’s superlative Chokepoints, a delectably readable narrative history of U.S. economic warfare against Iran, Russia, and China. U.S. sanction superpowers were exhibited most consequentially in response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, during which the United States and its European allies froze some $300 billion in Russian central bank assets and disconnected Russian banks from international markets, plunging the value of the ruble by a third.

Yet, as Fishman describes, the Russian economy didn’t completely melt down, as many predicted. Russia’s GDP fell by 1.4 percent in 2022, only to rebound to 4.1 percent and 4.3 percent in 2023 and 2024. This was in part due to Moscow’s adroit macroeconomic management and diversion of trade to China, though the exemption of Russia’s massive energy sales—accounting for around 40 percent of government revenues—from Western sanctions certainly helped.

Russia’s resilience highlights the continually eroding nature of the dollar’s sanctions potency. Russia has learned to live under economic siege, and while tightening up energy sanctions would deal one last major blow to the Russian economy, there’s little else left to sanction. Moreover, the Russian experience isn’t lost on other potential sanctions targets, such as China. As the world’s second-largest economy and largest trading power, there’s no way that Beijing can fully insulate itself from dollar exposure. But it continues to build up its defenses against U.S. financial warfare, most notably with its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)—a competitor to CHIPS—and efforts to conduct more trade in renminbi. In a future crisis, China will be better prepared to weather sanctions than it is today.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the renminbi is on the cusp of replacing the dollar internationally. Far from it: Uptake of CIPS has been lackluster, and the renminbi’s share of international payments is stalled at around 4.5 percent. A true internationalization of the renminbi would require China to open up its capital controls and convince the international financial community that it is a responsible stakeholder and will follow the rule of law. All very dubious prospects anytime soon.

Which brings us back to the reaction of markets to Trump’s tariffs. It’s one thing to economically batter Russia in the wake of its universally condemned invasion of Ukraine. It’s another to antagonize Western allies with hostile tariffs and the threat of economic escalation. This understandably spooked international investors but has also catalyzed a counterresponse in Europe, where European Central Bank chief Christine Lagarde is now banging the drum about strengthening the international role of the euro. There is even budding momentum around joint debt issuance, or a swap of existing national debt for pan-European bonds—a clever plan advocated by another former IMF chief economist, Olivier Blanchard—which would create a larger pool of bedrock euro “safe assets” to compete with U.S. Treasurys.

For sure, there is a long road to implementing any of this, and the barriers to structural integration of European financial markets are formidable. But the United States may have just inadvertently breathed life into the biggest potential competitor to the dollar.

Even if the dollar does lose some market share to the euro or renminbi, the boogeyman of a replacement of the dollar is highly exaggerated. In fact, the dollar has recently shaken off its post-April 2 panic and reverted to more normal behavior, with the dollar strengthening after Trump’s July round of tariffs, just as it should.

Rogoff and Blustein explore the potential for cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, and central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs, to transform the international payments ecosystem, but the end result is mostly a shrug. Crypto is useful for the underground economy—which Rogoff estimates at a whopping 17 percent of gross national income in advanced economies—but little else. Stablecoins or CBDCs could marginally improve payments efficiency but will still be linked to national currencies and therefore subject to the laws of economic gravity. Mostly, these innovations are solutions in search of a problem.

As both Rogoff and Blustein rightly point out, the biggest threats to dollar dominance lie not in international economic policy but in U.S. domestic politics. Rogoff highlights spiraling national debt unchecked by any political party, which could lead to a fiscal crisis or even outright default. Also threatening is the potential for runaway inflation that would erode the dollar’s appeal as a store of value.

The dollar’s most existential threat, however, is an upending of Federal Reserve independence and a general deterioration in the rule of law that would challenge the international investment community’s view of the United States as a safe bet. Unfortunately, this outcome is less fanciful these days, as Trump badgers Fed Chair Jerome Powell and fires statisticians who print numbers he doesn’t like.

Should the dollar’s status unwind because of such unforced errors, the costs would be structurally higher interest rates, less clout in global economic policymaking, and impotent sanctions powers. With both allies and rivals primed these days to find ways to buck the dollar, it would be wise for U.S. policymakers to keep these costs in mind. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin’s quote about U.S. democracy in the wake of the Constitutional Convention: Dollar dominance is ours, if we can keep it.

The post The Future of the Dollar Lies Within appeared first on Foreign Policy.