MOSUL, Iraq—South of Mosul, Saleh stood in front of a ruined station with his son. Along the tracks, train cars lie wrecked, pocked with bullet holes. A pair of skinny cats looked out from the doorway of the former ticket hall. “My father was the stationmaster here,” he said. “But he died in 2003 and I took over. That was also the year the trains stopped running on time. After ISIS, they stopped running at all.” He doesn’t know when they will begin again.

“My happiest memory as a child was laying my head on the tracks and listening for the trains coming,” he told me. “We knew these tracks went all the way to Turkey and onwards to Europe. ‘I’ll take us all on a trip there one day,’ my father said.”

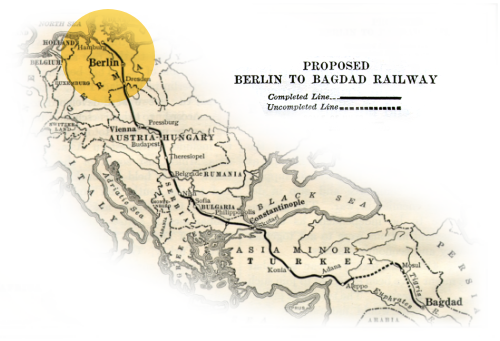

I was at Saleh’s ruined station as I retraced the route of the never-completed Berlin-Baghdad railway. Started in 1903, it was an audacious attempt by the German and Ottoman empires to bypass the Suez Canal and create a fast, overland route to the Persian Gulf.

For the Germans, it was a way to cement their alliance with the Ottomans and put pressure on Britain’s empire in India. Suspicions of oil in Mesopotamia only sweetened the prize.

For the Ottomans, who had seen the heart of their empire in the Balkans fragment and break away, the railway was an effort to make sure their Asian provinces didn’t go the same way. As Eugene Rogan, author of The Fall of the Ottomans, told me, “Railways were a way for the Ottomans to extend their effective reach into an area where they really had a very poor record of direct rule. To keep the Kurds close, keep the Arabs close, keep the Armenians close. Try to keep the disparate peoples of the empire bound to Istanbul’s rule.”

For both the German and Ottoman powers, it was also a way to move weapons across the continents as the world prepared for war.

A century after Berlin and Istanbul tried to bind Europe to the Gulf by rail, the unfinished line still traces today’s fractures and points to a new race to redraw Eurasian connectivity. Turkey touts its Middle Corridor, a Trans-Caspian route that seeks to compete with the Suez and sidestep Russia. Baghdad, meanwhile, is selling its ambitious “Dry Canal,” a proposed road and rail ink from the Grand Faw Port to Turkey and onward to Europe. Like the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, it promises to cut days off Suez transit times. Further west, Chinese capital funds Balkan rails for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), while the European Union talks “de-risking” and hardens its borders with “pre-accession” funds and Frontex deployments.

But like the original Berlin-Baghdad railway, these projects remain incomplete. Along the itinerary I traveled, oil and containers move slowly, while people often can’t move at all. Following the ghost route of the railway from Hamburg, Germany, to Basra, Iraq, reveals that the same track gauge can carry radically different dreams—from the kaiser’s eastern aspirations to those of the migrants and refugees today for whom connectivity is still just a mirage.

Germany

My journey to Saleh’s ruined station near Mosul began at the end of June in Hamburg, the railway’s intended northern terminus. A narrow tidal port on the shore of the North Sea, Hamburg still relies on its connection to the rails to stay competitive.

On the train south to Berlin, I met Bahar, an Iranian artist. Her reaction, when I told her about the Berlin-Baghdad railway, captured the broken promise of connectivity that I heard again and again along the route. “It is hard to imagine such a connection,” she said, “with so many wars and borders. … It is like something from a fairytale.”

In Berlin, I spoke to dozens of Iraqis and Syrians, many of whom walked here over months, some almost drowning on the boat from Turkey to Greece. Munzer, a Syrian man from Homs, said that of the 50 people he set out with, only five made it. He showed me a video from a friend who just returned to post-Assad Syria for the first time since 2011. There are fireworks and people dancing and hugging. “I can’t wait to do it, too,” he said, “to see my mother. I just need the paperwork.”

Hungary

I headed south, from Germany to Vienna, and then toward the Hungarian border. My train from Austria was full of Ukrainians, heading home to Kyiv. Along the banks of the Danube in Budapest, as people drank, ate, and posed for photos, the war in Ukraine felt very far away.

I ate dinner in a building that was once part of the Central European University—a departed symbol of another, more open future, from which the current president, Viktor Orban, has turned Hungary away. Staff in the kitchen hailed from Turkey, Israel, Palestine, and Iran. “We are proud of this,” said Anousha, a member of the team. “We are proud that multiculturalism in Hungary is not over.” In the Hapsburg decades, Budapest grew on trade that moved along the rails from Vienna to the East. Jews, Germans, Slovaks, Croats, and Greeks made a modern city together, even as the state pushed Magyarization. Contemporary “multiculturalism” in Budapest echoes an older imperial mobility—the habit of a city built by people who could move.

Later, I found Budapest Keleti station empty. There were no signs of the scenes that made world news in 2015, when thousands of refugees were blocked from boarding westbound trains and authorities briefly shut the terminus. No sign either that upgrades to the old Berlin-Baghdad line were financed by billions of dollars from Chinese banks in deals kept classified by the Hungarian government.

There were also no direct trains to Belgrade. Services in Serbia have been heavily impacted since November 1, 2024, when the roof of Serbia’s Novi Sad station—also refurbished by a Chinese consortium under BRI—collapsed, killing 16 people. I took the bus.

When I arrived, the Hungary-Serbia border hummed with the familiar choreography of overland travel. People milling about, waiting. Trucks idling. Birds flitting back and forth over barbed wire in the woods. The border is under construction, supported by funding from the EU, but also by China—great powers competing for influence.

Serbia

Sava-Danube country—the flatlands threading Novi Sad to the Hungarian border—flipped for centuries between the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian sphere, until Serbia won international recognition at the 1878 Congress of Berlin. The railways arrived with that new statehood. Belgrade’s main station was built in 1884, just in time for the new Orient Express and the later Berlin-Baghdad line.

When I arrived in Belgrade, whole sections of the city were shut down by nightly, mostly peaceful protests against President Aleksandar Vucic’s Russia-aligned government. The protests began with the Novi Sad station collapse and have since grown into a nationwide anti-corruption movement.

“This isn’t a revolution driven by want—the restaurants are full, people are doing OK economically,” said Sasa Jankovic, who previously served as protector of citizens (an independent authority responsible for investigating rights violations), and also ran for president. “It is about being fed up with being lied to and treated like fools by a corrupt gang. The failed railways are just a symptom of that. Of a state run by people for profit. Rather than as a way of doing big things together.” A century ago, the Berlin-Baghdad line broke on some of the same faults: big promises, murky finance, and the deadweight of politics.

Bulgaria

After another long bus ride east, I stopped in the quiet of St. Alexander Nevsky, the largest Orthodox cathedral in Sofia. Next to me in the pew was a man named Austin. He arrived here from Nigeria and later married a Bulgarian woman. He was at the cathedral to baptize his son. Later I stood with a priest on the balcony as he pointed out the nearby mosque, synagogue, and Catholic church. “You cannot build something like this, so close to each other, if you do not have some tolerance,” he said.

This geography isn’t an accident. Sofia grew as crossroads—a stop on the routes between Vienna, Belgrade, and Istanbul—so traders, students, and refugees kept arriving, and the city learned a practical tolerance. I saw that pragmatism again at the Council of Refugee Women in Bulgaria, where Victoria, a volunteer, helps a Syrian mother find a small gift for a newborn. The shelves are a jumble of shoes and toys: quiet logistics for lives in transit.

Turkey

The night train from Sofia to Istanbul arrived on time. From the station, I walked uphill to the German Fountain, where delicate Ws for “Wilhelm” in the mosaic roof are the only sign it was a 1900 gift from the German kaiser, part of a charm offensive aimed at getting approval for the Berlin-Baghdad railway.

Nearby, I drift through Topkapi Palace to its Baghdad Pavilion, built sometime between 1638 and 1639 to mark the Ottoman conquest of Mesopotamia. Its windows look over the Bosphorus, an imperial balcony looking out on the routes that fed the city. Elsewhere in the palace, I found relics purporting to be hairs from Prophet Muhammad’s beard, arm (and skull fragments) of St. John the Baptist, and the sword of King David. These pieces came to Istanbul as the empire absorbed pieces of the Arab and Byzantine worlds; the visual rhetoric of a state that cast itself as universal, heir to multiple sovereignties. Conquest here meant not only territory, but custody of routes, shrines, and stories.

Later, I walked downhill past the former Deutsche Orientbank and the rail and customs offices that handled the money and paperwork for the Baghdad Railway. The Orientbank has been reborn as a luxury hotel. A century ago, these facades fronted instruments of expansion: loans, bonds, concessions, timetables. Today they sell memory and pretty views. The infrastructure that once promised to bind continents is now a backdrop of the past.

I took a ferry to Asia, across the Bosphorus, heading towards the old Haydarpasa station. Once a glorious hub of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, it is now closed, under scaffolding.

Up the hill, two men were drinking coffee, Dursun and Typhoon. Dursun was mending a silk rug with expert fingers and a cigarette in his mouth. Typhoon made me coffee and talked about carpets as stories and history. He told me how the Dutch and British brought dyes and how buyers and Ottoman workshops adapted patterns to those markets. In his telling, a carpet is a physical manifestation of connections, as perhaps is the railway.

Later, in a café, I met Roxana, an animator from Tehran. Her husband is American, but she has waited two years for a visa. “Now, who knows how long it will take,” she said. If Dursun’s carpets are what open routes look like in wool and silk, Roxana’s paperwork is what closed ones feel like in life on hold.

I took the train more than 400 miles south to Konya, Turkey. It was very comfortable and very, very fast. This is the gleaming new infrastructure of the Middle Corridor in action. We rolled for a few hours along the Marmara Sea then onto the plateau, watching the landscape turn from green to dust.

As we climbed up into the Taurus mountains from the Anatolian plateau and towards the Syrian border to the south, the landscape changed again: pine woods, white limestone, and low brush, reminiscent of Provence. The railway curled up the hills through tunnels and across bridges, following the river valleys. I stopped at Eregli, a municipality in Konya. On the platform, the station bell was stamped by its German builders with the word BAGDAD—a reminder of the railway’s ultimate goal.

Above the tracks, the Cilician Gates passed through the Taurus Mountains to the west and the land fell away to the plains to the south and east. This was the mountain barrier that stopped the Germans from ever finishing the railway line. Now, there are crowds of vacationing Turks at the summit.

Further is the Varda Viaduct bridge, a masterpiece of German engineering, built between 1905 and 1916 to overcome one of the route’s last mountain barriers (and the scene of one of James Bond’s many almost deaths). Beyond the bridge is the beautiful Durak station, all yellow and cookie cutter German like a little outpost of Bavaria.

I attempted to go south, but the Turkish authorities wouldn’t let me cross into Syria. Even post-Assad, political barriers have replaced the mountains as the biggest choke point on the line.

Improvising, I headed east by bus and crossed the Euphrates in the dark, following the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline along Turkey’s southern border. The pipe is both a connection and a fault line. Baghdad and Erbil have fought for years over who controls and can sell Kurdish crude. A 2023 arbitration ruling against Turkey for letting the Kurdish Regional Government independently export its oil has turned off the tap for now.

Iraq

At the Iraqi border there is more waiting. Huge queues of trucks idle. This is the hinge of Iraq’s “Dry Canal.”

Waiting at the border, inching along, crushed in a tiny van with 30 others in the blazing heat, the frictionless dream of the original Berlin-Baghdad Railway feels very far away. Beyond the border, the skyscrapers and luxury developments of Erbil, Iraq, loom. “Gangsters” is the answer when I ask a fellow passenger where the money comes from.

Two checkpoints later and I was into territory formerly controlled by the Islamic State, on the outskirts of Mosul. Everyone I spoke to from here to Baghdad had stories of destruction, firefights, and suicide bombings.

My shared taxi skirted past the Mosul Grand Mosque, an unfinished Saddam-era project that has now restarted. Its enormous domes are clustered together like a flower, with cranes towering overhead but not much happening.

The beautiful carved doorways of the old city are shockingly ornate amidst the rubble, and no trains were running at Mosul station. The tracks were littered with abandoned carriages, blown over and torn into during the battle to defeat the Islamic State. The stationmaster, in suit and tie despite the heat and the ruin, told me that the railways “were the thing that connected the whole country together. Now war has destroyed all of it.”

In Mosul, I’m reminded of a conversation I had with Ali Allawi, the former Iraqi deputy prime minister and author of a biography of King Faisal I. “Railroad connections were critical to binding the country together,” he said. “In the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire, the problem was whether a centralized state could impose a kind of uniform identity on the country. And the degree to which central authority has to cede power to regional and provincial and local forces. This is constant tug of war. … It still hasn’t been resolved.”

Further south, in Baghdad, I walk for miles through the city, marveling at the architecture. Over breakfast, Kareem, a local journalist tells me, “Iraq is like a mystery box, every time you reach in, you find something new and different.” I eventually found my way into the Qishla building, built by the Ottomans and later occupied by the British. It was also where Faisal I was crowned at the birth of independent Iraq.

In a café around the corner, where men play dominoes and backgammon, Sobhy, a Syrian man told me that he likes Baghdad but it isn’t home. He touched his heart. I told him about the Berlin-Baghdad Railway then asked how he felt about it. “Like history failed,” he said.

Everywhere I went, I followed the traces and heard the echoes of empires and wars. But it is only at the end, after arriving on the night train from Baghdad to Basra, that I realized the most recent empire—the United States—has barely left a trace. Politically and institutionally, the 2003–2011 war’s imprint is everywhere, from the ongoing role of militias in state security, under the guise of the Popular Mobilization Forces, to the rentier fragmentation of the state. But the only physical evidence I found was “Happy mothers day 2005” written on the wall of one of Saddam’s abandoned palaces. “Love Ray,” it said.

Sitting by the sea on the Persian Gulf, at the end of my journey, as the blazing heat of the Basra day cooled, I asked Ahmed, a local academic, about the Americans and the absence of any physical signs that they were here. “We tried to erase it all,” he said. “Unlike the unfinished railway connecting us to the world, that’s one piece of our past that we wish to forget.”

I thought back to Saleh and his son, standing in their ruined station, and to a question a man called Mustafa asked me by the banks of the Tigris: “How come you can come here but we can’t go there?” It’s a question that hangs over every mile of the track I just followed, both ancient and new.

The post From Berlin to Baghdad on the Ruins of a WWI Railway appeared first on Foreign Policy.