Few museums embody a country’s history, values, and role in the world as much as the Louvre does for France. After a long stint as a royal palace that housed monarchs’ private art collections, the Louvre opened its gates to the people during the French Revolution. Since then, the museum has played a crucial part in France’s global ambitions of grandeur. Leaders from Napoleon Bonaparte to President Emmanuel Macron have relied on it to bolster the country’s soft power abroad.

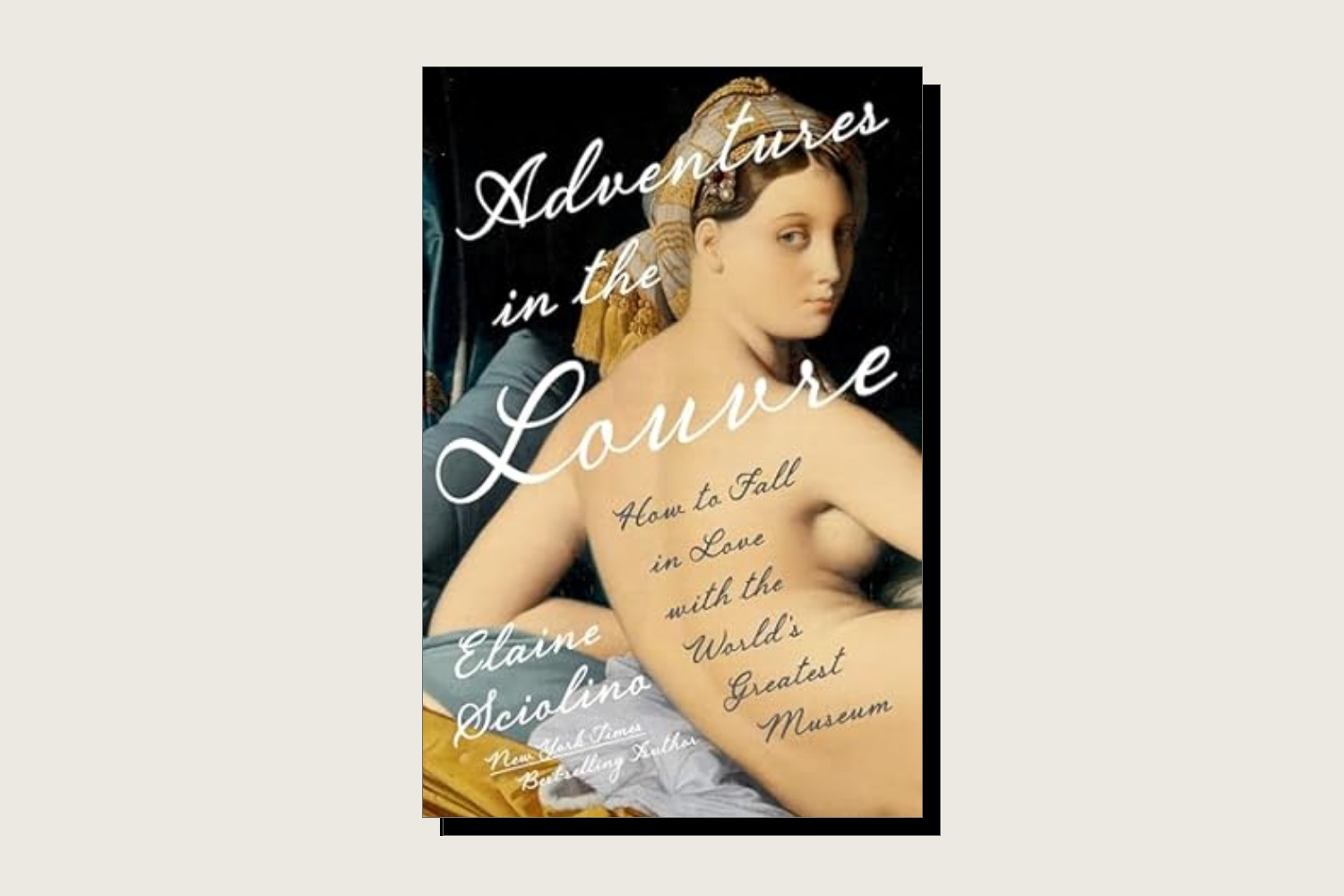

A new book takes readers through the museum’s countless staircases and hallways to present its complex past and current challenges. Adventures in the Louvre, by former New York Times Paris bureau chief Elaine Sciolino, is enriched by hours of interviews with top museum officials, including director Laurence des Cars. Sciolino aims to help visitors find their bearings in an enormous, often overwhelming space.

Every year, up to 10 million people admire the 30,000 artworks in the Louvre’s exhibits, which are spread over 780,000 square feet, per Sciolino’s count—making it the largest, most visited museum in the world.

Sciolino covers the museum’s most famous artworks—such as the Mona Lisa, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and the Venus de Milo—as well as less well-known sections such as the Consultation Room of Prints and Drawings, where anyone can hold in their hands the original work of some of the world’s greatest artists. She highlights overlooked masterpieces, such as Titian’s eye-wateringly beautiful Man With a Glove, which had the bad luck of being placed near the Mona Lisa. She also suggests alternative ways to explore the museum’s contents, such as by focusing on how women and people of color are portrayed or tracking the representations of food and animals.

As a Paris resident blessed with free press access to the Louvre and an office just a few blocks away, I was no stranger to the museum’s treasures, but it was a pleasure to go back with Sciolino’s book under my arm, hunting for hidden gems. My own advice to Louvre visitors: Most people who plan to spend a whole day at the museum tend to head to the Mona Lisa first, so use the morning to explore the other wings in peace. You could even find yourself, as I did, enjoying the giant Peter Paul Rubens paintings in the Galerie Médicis without a soul in sight.

But Adventures in the Louvre is much more than a guide for art buffs. Through the prism of the museum’s transformations over the centuries, Sciolino also tracks France’s changing self-image and place in the world, showing how successive French regimes have leveraged the Louvre to support their visions for the country.

The Louvre opened to the public in 1793, and the deposed royal family’s collections suddenly became accessible to all—an important symbolic step to mark the tectonic shift from monarchy to the rule of the people. In the following years, Napoleon planned the Louvre’s transformation into the world’s first global museum. He enlarged the space, filling it with art that France had looted all over Europe, and using it to aggrandize himself—to the point of renaming the museum the Musée Napoléon and marrying his second wife there in 1810. He built a triumphal marble arch celebrating his victories in the courtyard, officially transforming the Louvre into a showcase of France’s imperial glory.

Sciolino illustrates how the Louvre remained central to France’s official narrative about its own global prominence well after the era of Napoleon, all the way to the current Fifth Republic. In the 1980s, Socialist President François Mitterrand launched the Grand Louvre project, which added roughly 300,000 square feet of usable space and built the famous glass pyramids designed by Chinese American architect I.M. Pei. The initiative had to do with Mitterrand’s “two obsessions: the glory of France and his own legacy,” Sciolino writes.

Since the 2000s, France has used the Louvre as an instrument of soft power abroad. One of the book’s chapters is devoted to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, a spin-off of the museum in the United Arab Emirates’ capital greenlit by French President Jacques Chirac in 2007 and inaugurated by Macron a decade later. As part of the deal, France received a whopping $1.1 billion for the lease of the Louvre’s name by the new museum for 30 years, as well as for its expertise and loan of artworks.

As part of the museum deal, the UAE also ordered 40 Airbus A380 aircraft and billions of dollars’ worth of weapons from France. Many French academics and museum curators criticized the agreement with the UAE, citing the country’s poor human rights record, the risk of watering down the Louvre brand, and the giving away of precious collections in exchange for economic gains. In 2006, a column in leading French newspaper Le Monde even said the move was tantamount to “selling your soul.”

But Sciolino doesn’t emphasize enough that the France-UAE deal was hardly the only initiative of its kind in recent years. A similar partnership was established from 2006 to 2009 between the Louvre and Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, which received just under 200 exhibits, including paintings by Raphael, Velazquez, and Rembrandt, in exchange for $6.4 million to help restore the Parisian museum’s decorative arts galleries.

Nor is French cultural diplomacy limited to the Louvre. During a visit to the United Kingdom in July, Macron announced that France would loan the 11th century Bayeux Tapestry to the British Museum starting in September 2026, a move designed to underscore improved relations between the two countries.

The tapestry is widely accepted to have been made in England and depicts events before the Norman conquest of the country, but it hasn’t left French soil in over 900 years; by Macron’s own admission, France has long been reluctant to consider letting the masterpiece out of the country. The agreement was one of several deals clinched during the trip, from immigration to nuclear deterrence.

Culture, art, and the Louvre have played an important role in Macron’s domestic political narrative, too. Sciolino notes that Macron chose the Louvre as the backdrop for his victory speech after he was first elected president in 2017. Cameras followed him as he walked across the courtyard to the notes of the European anthem, all the way to a stage placed in front of Pei’s lighted pyramid.

Eight years on, Macron—who lost much of his political clout after a snap election that he called last year produced no clear parliamentary majority—has made the Louvre a central axis of his efforts to build his legacy. In a speech in January in front of the Mona Lisa, Macron announced a major overhaul of the museum, including the creation of a separate section to house Leonardo da Vinci’s painting and the opening of a new entrance to alleviate overcrowding at the current main access at the pyramid.

The project will also entail a less flashy but badly needed modernization of the Louvre’s aging buildings, which are plagued by leaks, cracked roofs, and moth invasions. The goal is to increase museum capacity to 12 million visitors per year—over 3 million more than in 2024.

Though Adventures in the Louvre does mention the ongoing debates about these changes, it presumably went to press too early to include mention of Macron’s decision to step in. But the political significance attached to Macron’s Louvre initiative is hard to overlook. In his speech, Macron described it as “a new step in the nation’s life” that is “important for our country’s culture but also for the battles we are fighting.” The project has been labeled “Louvre New Renaissance,” echoing the name of Macron’s party.

French presidents traditionally consider culture an area in which they can intervene directly, without delegating oversight to their governments, said Laurent Martin, a history professor at Sorbonne Nouvelle University in Paris. “It allows presidents to leave a legacy in a much more effective and immediately visible way than anything else,” he told Foreign Policy, adding that given Macron’s domestic political woes, culture and foreign affairs are all the president has left to work with.

Macron already embarked on a similar endeavor with the restoration of Notre Dame, which was ravaged by a fire in 2019. The cathedral reopening just five years later, with a grandiose ceremony attended by 1,500 world leaders and dignitaries, was widely seen as a success for the president. Whether the Louvre will be a similar story remains to be seen. The renovation is estimated to cost between $820 million and $940 million over 10 years. Sources close to Macron and familiar with the project told French media that taxpayers will only foot a small part of the bill, with the rest being financed by the museum’s own revenues and private donors.

But some observers consider Macron’s plans overly optimistic. The minority government led by Prime Minister François Bayrou is seeking to trim $47 billion from France’s budget to rein in its deficit and public debt. Just before Macron formally announced his plan, a government spokesperson—in a rare rebuke—stressed that a massive injection of public cash for the Louvre was out of the question.

Macron’s France continues to aspire to an outsized international role. But its real clout on the world stage often falls short of its ambitions. The Louvre, like France, has a glorious past and grand projects for the future. But amid a budgetary and political crisis, it also faces huge problems while lacking the resources to address them. Now more than ever, the museum is the perfect symbol for the nation.

The post How the Louvre Made France appeared first on Foreign Policy.