As National Guardsmen are sent for a second time in recent months to a U.S. city whose local leaders made no requests for their support, we may be seeing the Trump administration’s new national defense strategy play out in unprecedented ways ill-matched to military capabilities.

Civilian and uniformed Pentagon officials have said publicly that this administration is prioritizing the geographical United States in its national security policy, a departure from recent administrations—including Trump’s first—that have described conflict with China in the Indo-Pacific or terrorism in the Middle East as the biggest threats to America.

“I think we’re learning in real-time what that means,” Mark Cancian, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International studies, told Defense One.

Currently, the administration is operating under an interim NDS that is “focused on defending the homeland,” with China and the Indo-Pacific a lower priority, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told the Senate Appropriations Committee in June.

“We did an interim national defense strategy almost immediately upon arriving, because with a new administration, our planning guidance was from the previous administration—that we think had the wrong priorities, or some of the wrong priorities—and by issuing that interim national defense strategy, it allowed our building to plan around the priorities of President Trump,” Hegseth said.

The interim NDS, which is classified, was finalized in March. An unclassified version exists but has not been released to the public—another change from the Biden administration, which published unclassified versions of both the interim and final NDS.

In May, the Pentagon announced that work on the final NDS would begin. The effort is being led by Defense Undersecretary for Policy Elbridge Colby, who has long proclaimed China to be the leading threat to America and who helped establish the Indo-Pacific as the priority theater in the 2018 NDS. This time around, it seems, Colby has been instructed to move the homeland to the top of the agenda, and bump China and Russia down.

Despite its second-place ranking, there’s no indication that the Indo-Pacific is getting a demotion in terms of attention or funding.

“And that’s certainly true this year,” Mark Cancian said.

But that’s largely thanks to the one-time boost of the reconciliation bill. The defense budget request itself is flat in terms of dollars, and effectively a dip because of inflation. If the next years’ budgets include maybe a 2-percent hike, that might cover losses in spending power, Cancian said.

“But you know, if the budget is flat in nominal terms…then, you know, you’re losing 5 percent a year,” he said. “And I mean, that doesn’t take very long before you’ve made some deep cuts.”

Hegseth didn’t mention Russia at all in his characterization of the strategy, except insomuch as the administration is pressuring Europe to spend more on its own defense as Moscow continues its war on European soil.

That will enable the Pentagon to shift forces and resources elsewhere, he said: “…burden-sharing for our allies and partners, making sure that they’re stepping up so that we can focus where we need to.”

Defending the homeland

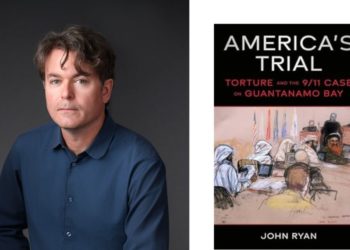

Weeks after the interim NDS came out, Gen. Joe Ryan, the Army’s deputy chief of staff for operations, told a conference audience that while the service has been balancing requirements in the Indo-Pacific and Europe, “I can’t leave out maybe the No. 1 priority theater today, and that’s the homeland.”

“But I would argue it hasn’t made a big splash quite yet, and it needs to, because it’s an important document,” Ryan said.

What’s now playing out is the administration’s interpretation of domestic defense.

It started in February with an increase in troops deployed to the southern border, followed by the creation of a militarized border zone in April. That required bumping up the number of troops assisting Customs and Border Patrol from about 2,000 to 10,000.

“For a while, I was a little worried that the requirement for [U.S. Northern Command] to seal the border, it would end up taking tens of thousands, but that doesn’t seem to have happened,” Cancian said.

The administration’s first ambitious stateside project is “Golden Dome,” envisioned as an Israeli Iron Dome-like web of sensors and missile-defense weapons—including some in orbit—intended to prevent aerial attacks anywhere in the United States.

The effort got a big boost in the recently passed reconciliation bill, with a $25 billion downpayment on what the administration has projected will be a $175-billion endeavor and be at least somewhat operational by 2028. Many experts have called the plan unworkable, even with far more time and money.

The administration has been tight-lipped on progress. Earlier this month, the Defense Department barred officials from mentioning Golden Dome at the annual Space and Missile Defense Symposium in Alabama, a forum traditionally used to showcase Pentagon efforts and discuss needs with defense contractors. Two days later, DOD hosted an unclassified Golden Dome industry day, but banned reporters from attending.

On Monday, Trump—with Hegseth by his side—announced that he would be taking control of Washington, D.C.’s police department and deploying 800 members of the district’s Army National Guard to support them in efforts to fight crime.

“I think this is part of that focus on national security, because I think that there’s a big push politically, domestic politics—aside from views about national security—that they like using troops to make a political point,” Cancian said.

But the Guard really isn’t well-suited to law enforcement missions, he said. Even when units were sent to guard the Capitol building after the Jan. 6 riot, troops were limited to crowd control and manning entrances to a fenced-in complex.

“Military forces have the wrong attitude about civilians. Law enforcement is trained to see civilians as citizens who deserve protection, except in the most extreme circumstances,” Cancian and Chris Park, a CSIS research associate, wrote in an analysis published Tuesday. “Military personnel are taught to treat civilians as potential threats and to always be ready to respond. Crowd control—in other words, dealing with unruly citizens—is the primary law enforcement training the National Guard receives.”

Service members also don’t receive the same training that police do when it comes to citizens’ rights and use of force, they wrote. This could present issues not only with Guardsmen assisting D.C. police, but with other possible domestic missions that are in line with the current national defense policy: immigration enforcement and counter-drug operations.

Six states have deployed Guardsmen to assist with Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids.

“Putting aside whether you think that crime is out of control or whether you think that action is needed, it’s just not a very good tool for it,” Cancian said.

D.C.’s Home Rule Act allows the president to federalize its police force for 30 days, meaning the Guard’s mission is expected to last at least as long. The president said Wednesday that he would seek authorization from Congress to extend his takeover.

A White House press release about the mission does not give an end date, saying only that the “Guard will remain mobilized until law and order is restored.”

The post Trump’s national defense strategy is focused on the homeland. So far, that has included troops in the streets. appeared first on Defense One.