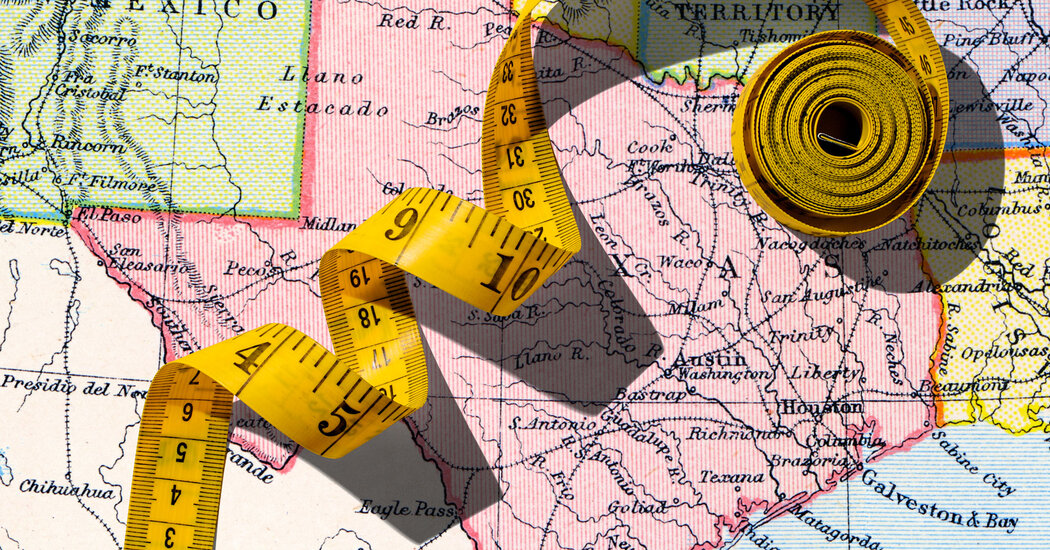

Call it MAG: Mutually Assured Gerrymandering. First Texas, under pressure from the White House and Justice Department, began redrawing its district maps in the middle of the decade — although the process is normally undertaken after a new census. Now several blue states have said they may attempt to follow suit, which would mean warping their own districts to further boost the Democrats.

Gerrymandering has long been a problem, but this is a new level of insanity that should spur urgent demands for reform. Addressing the problem requires states or Congress to step up and produce fair maps, judged by objective measures. My research suggests one way to do so, based on how far a map departs from perfect compactness.

Redistricting isn’t my usual beat. I’m an economist who dissects race and inequality to design fixes for stubborn social ills — and a venture capitalist who then backs the market solutions those findings inspire, instead of letting them languish in obscure academic journals or well-meaning nonprofits.

Back in 2004, soon after earning my Ph.D., I found myself in the Harvard Society of Fellows chatting with a Supreme Court justice. I asked what single problem math or economics could solve for the Court. The answer was instantaneous: Give us an objective yardstick for political maps. (Others have tried their own remedies).

After months huddled around a whiteboard with a sharp graduate student, Richard Holden, fueled by too much bad Harvard Square coffee, we created a measure we call the “Relative Proximity Index.”

Picture every voter as a dot on the state map. First, we pin down the geometric minimum — the most compact way to bundle those dots inside the state’s jagged borders into its exact number of congressional districts, each with equal population, whether that means wrapping around Florida’s panhandle or hugging Georgia’s slanted shoulder. Then we compare the map the legislature actually draws to that floor. The ratio is the Relative Proximity Index. An R.P.I. of 1 means you’ve hit the geometric ideal; an R.P.I. of 3 means voters within a district would live — on average — three times farther apart than necessary.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

The post Geometry Solves Gerrymandering appeared first on New York Times.