It’s hard to imagine a library that doesn’t carry “Fahrenheit 451.” But making Ray Bradbury’s classic novel about book burning available to libraries in an e-book format can be its own little dystopian nightmare, according to Carmi Parker, a librarian with the Whatcom County Library System in northwest Washington.

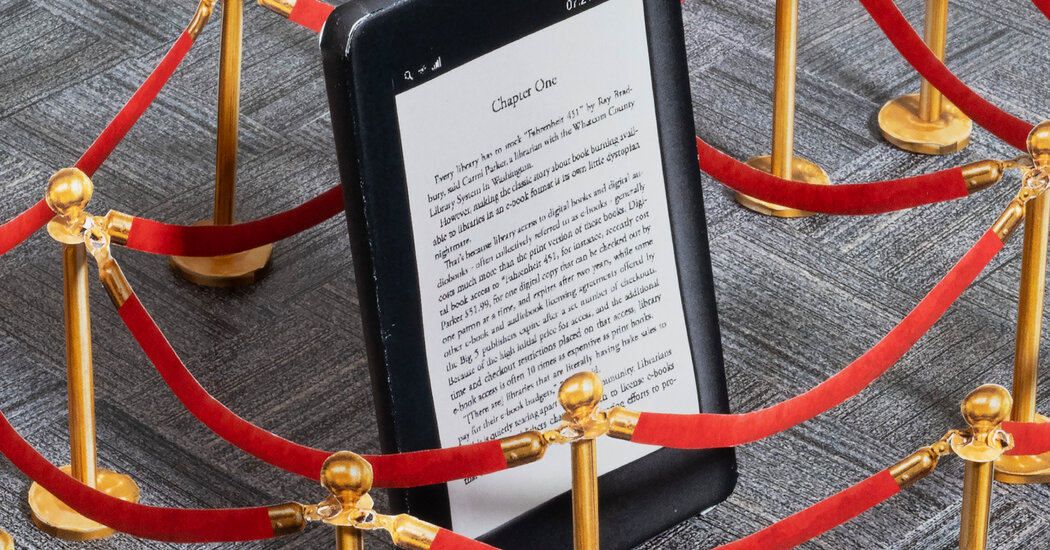

That’s because library access to digital books and digital audiobooks — often collectively referred to as e-books — generally costs much more than the print version of these books. The Whatcom system must pay $51.99 to license a digital copy of “Fahrenheit 451,” which can be checked out by one patron at a time, and which expires after two years. Other licensing agreements offered by major publishers expire after a set number of checkouts.

Adding together the initial cost with time and checkout restrictions can make library e-book access as much as 10 times more expensive than print books. Parker said this is forcing some libraries to launch “bake sales to pay for their e-book budgets.”

The issue is causing tension in the book community. Librarians complain that publishers charge so much to license e-books that it’s busting library budgets and frustrating efforts to provide equitable access to reading materials. Big publishers and many authors say that e-book library access undermines their already struggling business models. Smaller presses are split.

But the problem is only getting worse as more people turn to their libraries for e-book access. Last year, the e-book library borrowing platform OverDrive reported that more than 739 million digital books, audiobooks and magazines were borrowed over its Libby and Sora apps, a 17 percent increase from the year before.

The often bitter debate has lately moved from the library stacks and into state capitals. In May, the Connecticut legislature passed a law aimed at reining in the cost of library e-books, and other states have introduced similar legislation.

The Connecticut law restricts the types of e-book purchases libraries can make. For instance, librarians won’t be able to purchase e-books for which interlibrary loans are prohibited or enter into licensing agreements that are simultaneously time-limited and cap the number of checkouts permitted.

Ellen Paul, the executive director of the Connecticut Library Consortium, said these provisions will prevent libraries in the state from buying many e-books under their current terms and therefore force publishers to the bargaining table. Librarians will then be able to negotiate e-book prices the same way they currently negotiate prices for print books — frequently paying less than the jacket price.

Paul said this legislation is needed because e-book pricing is a problem for every library in the country. “Every year, libraries spend more and more of their budget feeding the beast that is e-books to meet their patrons’ demands, and yet we still have wait lists of over six months long to get that book that you want.”

The Connecticut law has a trigger clause, so it will only go into effect after a state or states with a total or combined population of more than 7 million move forward with similar laws. New Jersey is currently exploring similar legislation that, if enacted, would trigger Connecticut’s law.

Policymakers in Hawaii and Massachusetts are also exploring e-book legislation, and library advocates are talking with politicians in several other states about introducing bills.

Publishers and authors argue that the long wait times for library e-book checkouts, which these legislative efforts hope to alleviate, are the only market force encouraging people to actually buy e-books. “When it’s so easy to get a free e-book, a perfect e-book, every time, why would they ever buy an e-book?” said Mary Rasenberger, executive director of the Authors Guild. “The only friction now that exists for getting library e-books is the wait time.”

She added that authors need every penny in royalties they can get. A 2023 Authors Guild survey found the median income for authors from their books was just $10,000 annually. “We have always been supportive of more library funding, but don’t make authors subsidize access,” Rasenberger said. (Several authors declined to comment by name for fear of review bombing.)

The Guild opposes Connecticut’s new law and similar legislative efforts elsewhere. Umair Kazi, the organization’s director of advocacy and policy, said that if librarians can’t reach a deal with book sellers, “publishers may exit the Connecticut library market.”

Smaller publishers say their authors are largely happy just to get their books into the digital holdings of libraries. Joe Matthews, chief executive officer of the Independent Publishers Group, said the current question is part of a longer philosophical debate in the books business: “If someone checks out an e-book from a library, is that a lost sale?” he said. “No one really has the data set to prove anything.”

Even so, Matthews said that for the authors he works with, library exposure tends to be a good thing, and not represent lost sales. This is why his group allows libraries to purchase, rather than license, e-books and audiobooks from dozens of publishers at a standard consumer price.

In the late 2010s, Macmillan, one of the industry’s so-called Big Five publishers, introduced a policy called “windowing” that permitted only one e-book copy to be borrowed for the first eight weeks after a new book was released. Rasenberger, from the Authors Guild, was open to the idea, but librarians “absolutely hated it,” she said. Some librarians even carried boxes of petitions protesting the practice to Macmillan’s New York City offices.

In 2021, New York’s governor, Kathy Hochul, vetoed legislation that would have required publishers to offer libraries e-book access with less expensive and restrictive terms, arguing that it violated federal copyright law. The following year, a Maryland law aimed at lowering library e-book costs was struck down by a U.S. District Judge who also cited federal copyright law.

The Connecticut law and proposed New Jersey legislation were designed with Maryland and New York in mind, so are not based upon copyright, said Kyle K. Courtney, a librarian and lawyer and director of Harvard Library’s Copyright and Information Policy.

Courtney, who formed an advocacy group to tackle the issue, said that instead the proposed legislation builds off each state’s existing consumer protection law, a good strategy given that “libraries are also consumers.”

Beyond price, librarians are concerned that e-book licenses interfere with the mission of libraries to preserve history and culture. A one or two-year license doesn’t work for research libraries, said Alan Inouye, a consultant and former director of public policy for the American Library Association. “Their time horizon is in centuries.”

Inouye is also disappointed that, instead of increasing access as they once seemed poised to do, digital books have complicated the ecosystem. Now, librarians are merely hoping they can convince publishers to treat e-books more like print books.

“It’s really sad because we’re limiting ourselves to what we had before,” he said. “In effect, we’re excluding the possibility of being better in the digital world.”

The post Libraries Pay More for E-Books. Some States Want to Change That. appeared first on New York Times.