Muhammadu Buhari, who died on Sunday at age 82, was one of two leaders of Nigeria, along with Olusegun Obasanjo, to rule the country both as military dictator and as civilian president. He was a human rights disaster in the first role and largely inept in the second.

Born on Dec. 17, 1942, Buhari joined the Nigerian Military Training College in Kaduna at age 19 and also attended training schools in the United Kingdom. He was already a brigade major by the mid-1960s, when the Nigerian Civil War broke out. From all accounts, he performed with distinction on the battlefield, especially during the conflict’s earlier stages as part of the 1st Division’s incursions into key rebel towns and villages.

His appetite for power may have been whetted by his participation, along with other military officers, in two early coups: The first, in 1966, brought Yakubu Gowon to power, and the second, in 1975, elevated Murtala Muhammed. His involvement in those actions probably aided his ascension to positions of greater authority within the military and the government.

Buhari became assistant adjutant general of the 1st Infantry Division Headquarters in 1971 and acting director of transport and supply at the Nigerian Army Corps Supply and Transport Headquarters in 1974. Muhammed appointed him governor of what was then North-Eastern State in 1975, and Obasanjo made him federal commissioner for petroleum resources and chairman of the newly created Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. in 1976 and 1977 respectively.

Military officers led by Gen. Ibrahim Babangida launched another military coup in December 1983, pushing out the ineffectual Shehu Shagari, the first democratically elected president of Nigeria. They appointed Buhari, as the senior officer among the coup plotters, to lead the country.

Nigerians then were yearning for a leader with more discipline, and Buhari promised to provide it. What they got instead was a regime still remembered, decades later, for a severity and joylessness exceeded only by the homicidal Sani Abacha (1993-1998), whose appetite for slaughter and lucre has no parallels in Nigerian history.

Shortly after he became head of state, Buhari reportedly made known his resolve to “tamper with press freedom,” and soon thereafter his administration enacted the infamous Public Officers (Protection Against False Accusation) Decree, otherwise known as Decree No. 4. Among other vague provisions, the decree made it an offense to publish “any message, rumour, report or statement … which is false in any material particular or which brings … the Federal Military Government or the Government of a State or public officer to ridicule or disrepute.”

As it happens, Decree No. 4 was only the tip of a spear plunged into the heart of Nigeria’s vibrant civil society that—then and now—comprised a raucous political class and perhaps the freest press in Africa.

As with many initiatives that Buhari championed over a long political career, this one contained a germ of good intention. The attempt to corral the press was part of a broader campaign—called the War Against Indiscipline—to instill some order into public life in Nigeria. Buhari’s efforts throughout his career were aimed at combating “dishonesty, indolence, unbridled corruption, and widespread impunity,” as he put it in 2016, in order to instill virtues such as honesty and hard work in the Nigerian public, something that even the most implacable enemies of his first regime might have conceded was needed. Likewise, the decision to arraign state governors and other leading politicians on corruption charges wasn’t a terrible idea. Yet, if Buhari had a signal personality flaw, it was a tendency to go overboard.

Many Nigerians found it difficult to comprehend why someone cheating on school or college examinations deserved a 21-year prison sentence or why civil servants had to perform frog jumps in public for being tardy. The moral vulgarity of the political elite probably called for more than a slap on the wrist, but a lifetime ban from public office, as was the case with some state governors and other key political figures, seemed like overkill.

Yet because the Buhari administration had estranged itself from both the media and the political elite, those very networks failed to alert him to widespread discontent across the populace. Babangida, then Army chief of staff, apparently had his finger closer to the pulse. He launched yet another coup in 1985 that was met with open jubilation.

Babangida’s coup-day description of Buhari as “too rigid and uncompromising in his attitudes to issues of national significance” might have been self-serving, but it captured the frustration many Nigerians felt with Buhari’s short-lived tenure as military leader.

Had Buhari practiced what he preached, Nigerians might have endured the rigidity. But rumors of preferential treatment for his associates and ethnic allies rapidly hardened into concrete allegations. In 2021, the Human Rights Writers Association of Nigeria put out a statement saying that since 2015, Buhari had “maintained the illegal and unconstitutional practice of posting only Northern Hausa/Fulani Muslims to head the entire internal security architectures such as Nigerian Customs Service, Nigerian Immigration Service, Nigerian Police Force, Department of State Services, National Intelligence Agency and Nigerian Army.”

Although Buhari’s military tribunals imposed improbably long sentences on many leading political actors for corruption, there were curious exceptions. While Shagari, the deposed president, was merely placed under house arrest, Alex Ekwueme, his vice president, was held in a maximum-security prison for 20 months despite no charges being brought against him. Similarly, Gov. Adekunle Ajasin of Ondo State was jailed even though a military tribunal had twice found him innocent.

Babangida, for his part, detained Buhari for three years, and from all indications, the latter never got over what he saw as an act of betrayal by his previously trusted colleague.

Buhari’s first chance at rehabilitation came in 1994, when Abacha appointed him executive chairman of the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF), set up with the ostensible aim of upgrading the country’s physical infrastructure. Although Buhari accepted the appointment on the condition that he would be given a free hand to run it as he deemed fit, he was accused of being criminally aloof from its everyday operations.

According to journalist Ray Ekpu, Buhari “was absent-minded and had capriciously surrendered the operational powers of the PTF” to others without diligent supervision. Though there was no evidence that Buhari knew about the massive corruption going on, his underlings went on an uncontained looting spree. The PTF under Buhari also faced accusations of “lopsided distribution” of projects between the country’s north and south, accentuating sectarian tensions, according to Ekpu.

Buhari denied the allegations, boasting to a national newsmagazine, “My integrity is intact.” Still, he seemed to be someone with a political split personality—combining a reputation for transparency with a high level of tolerance for malfeasance among those he favored.

That Buhari had a zeal for pursuing public good seems clear; at the same time, he never really distinguished himself at it, and—intriguing for a former soldier—he was often deeply lacking in discipline.

He seemed to revel in the status offered by high positions more than in the execution of his duties. Persistent in his efforts to attain office—as evidenced by the fact that he ran for the presidency three consecutive times (2003, 2007, and 2011) before finally winning a fourth contest in 2015—he achieved little once he got there.

Buhari’s tenacity was probably driven, at least in part, by a need to close the circle on his controversial early tenure as military dictator. In any event, Nigeria in 2015 was a country in desperate need of relief from former President Goodluck Jonathan’s general ineptitude. In particular, Jonathan had failed to put down a vicious insurgency by Boko Haram, and Buhari, who had the distinction of having commanded three Nigerian Army divisions, was deemed the right man for the job.

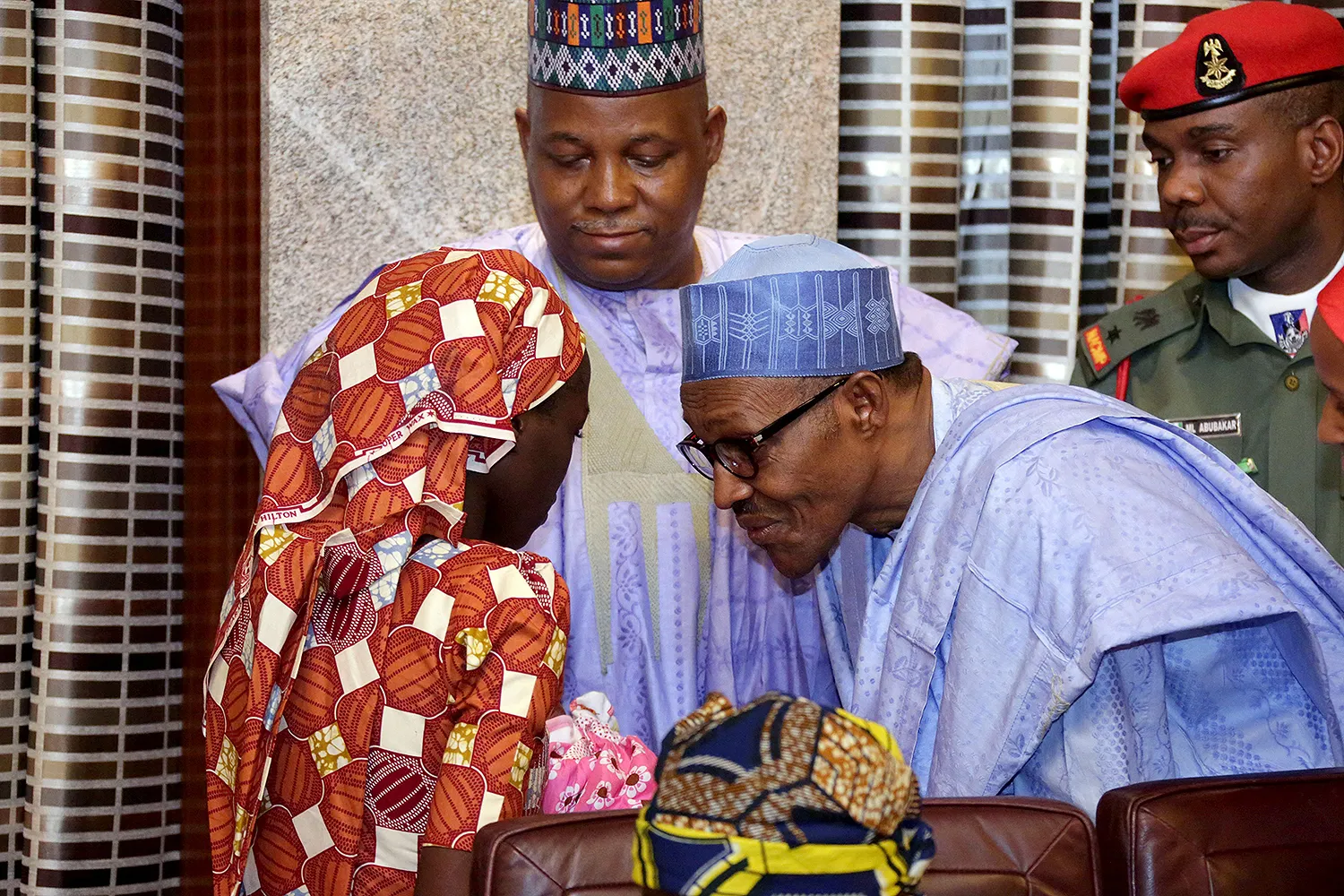

The six months or so following Buhari’s swearing-in as president in May 2015 remain the high-water mark in public solidarity with a Nigerian leader. Voters expected Buhari to use his experience as a former soldier to take the battle to Boko Haram insurgents who were steadily gaining ground in the country’s northeast and had, in April 2014, carried out the brazen kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok, in Borno State.

Sadly, the six months it took Buhari simply to form a cabinet would set the tone for a disappointing eight-year reign, when nearly every aspect of socioeconomic life in Nigeria took a turn for the worse. People felt so insecure due to rising crime rates across the country that at least one state governor urged them to procure arms to defend themselves and ordered the state commissioner of police to issue licenses to residents “willing and fit to bear arms,” as the newspaper This Day put it. The economy suffered similarly: The constant threat to people’s security snuffed out the life of whatever remained of an anemic private sector.

Buhari’s poor first term and diving popularity raise the question of why he was reelected in 2019, and handily at that—56 percent of votes cast, compared with his challenger Atiku Abubakar’s 41 percent. At least three factors appear to have worked in Buhari’s favor. One was the advantage of incumbency, particularly in terms of mobilization and deployment of state power and resources. Second, Buhari, all told, still enjoyed the support of powerful retired Army generals who preferred him to a challenger whom some of them (former President Olusegun Obasanjo for one) had fallen out with. Finally, Abubakar was the standard-bearer of a political party, the Peoples Democratic Party, that had been ushered out of office only four years earlier in part due to public disgust at its corruption and fecklessness. In the end, Abubakar simply couldn’t persuade the electorate that he was any different from the man he was aiming to unseat.

In late 2020, the official unemployment rate reached a staggering 33 percent. Corruption continued to thrive, and Buhari’s perennial protestations that he was doing everything possible to stymie it were undercut by his indefensible pardons of former governors convicted of looting their state treasuries. Buhari also imposed a seven-month ban on Twitter after the social media platform deleted one of his tweets—evidence of a lingering tyrannical cast of mind.

In fairness, any leader thrust into the vortex of Nigeria’s raucous ethno-regional politics, especially at that historical moment, might have similarly struggled. No single person can be justly expected to fix all of a country’s problems or even most of them. But that Buhari failed on almost every front—despite the time and goodwill at his disposal—makes his failure even more perplexing.

Addressing the media on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 2012, at a time when Buhari was still in the hunt for Nigeria’s ultimate office, he conceded that the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 had made him a late convert to the virtues of democracy: “It was then that I believed, personally, in my own assessment, that [a] multiparty democratic system was and is still superior to despotism.”

There is little reason to doubt the genuineness of his conversion or even his feelings for his country. That he ultimately fell short is proof that good intentions and proclamations of moral rectitude, while desirable, are not enough.

Reina Patel contributed to the research for this article.

The post Despite Good Intentions, Muhammadu Buhari Failed Nigeria appeared first on Foreign Policy.