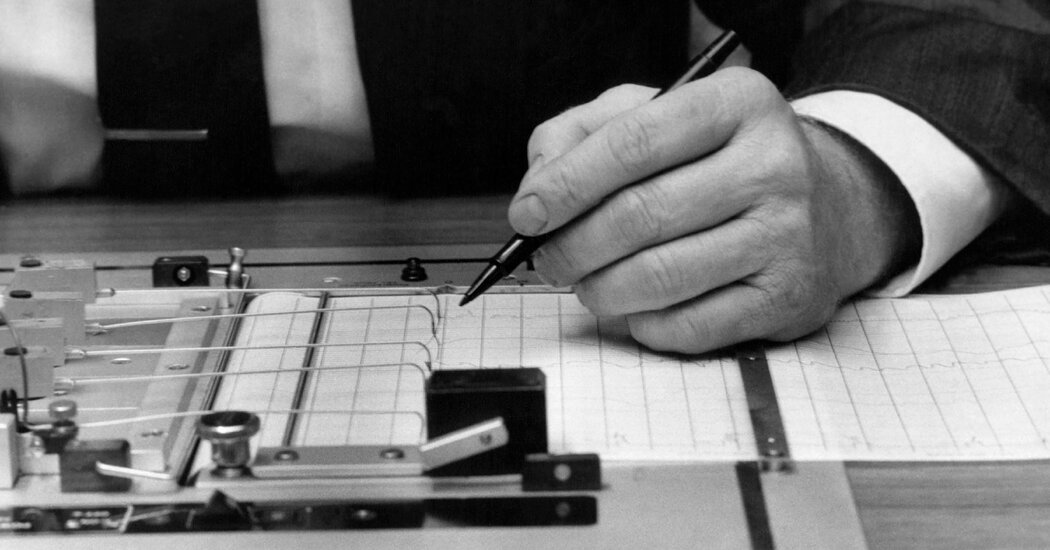

Typically, the F.B.I. has turned to polygraph tests to sniff out employees who might have betrayed their country or shown they cannot be trusted with secrets.

Since Kash Patel took office as the director of the F.B.I., the bureau has significantly stepped up the use of the lie-detector test, at times subjecting personnel to a question as specific as whether they have cast aspersions on Mr. Patel himself.

In interviews and polygraph tests, the F.B.I. has asked senior employees whether they have said anything negative about Mr. Patel, according to two people with knowledge of the questions and others familiar with similar accounts. In one instance, officials were forced to take a polygraph as the agency sought to determine who disclosed to the news media that Mr. Patel had demanded a service weapon, an unusual request given that he is not an agent. The number of officials asked to take a polygraph is in the dozens, several people familiar with the matter said, though it is unclear how many have specifically been asked about Mr. Patel.

The use of the polygraph, and the nature of the questioning, is part of the F.B.I.’s broader crackdown on news leaks, reflecting, to a degree, Mr. Patel’s acute awareness of how he is publicly portrayed. The moves, former bureau officials say, are politically charged and highly inappropriate, underscoring what they describe as an alarming quest for fealty at the F.B.I., where there is little tolerance for dissent. Disparaging Mr. Patel or his deputy, Dan Bongino, former officials say, could cost people their job.

“An F.B.I. employee’s loyalty is to the Constitution, not to the director or deputy director,” said James Davidson, a former agent who spent 23 years in the bureau. “It says everything about Patel’s weak constitution that this is even on his radar.”

The F.B.I. declined to comment, citing “personnel matters and internal deliberations.”

Already, President Trump’s political appointees have tightened their grip on the F.B.I., forcing out employees or putting others on administrative leave because of previous investigations that ran afoul of conservatives and a belief that the bureau had been politicized. The list has ballooned to include some of the most respected officials at the highest ranks of the bureau.

Others have left, fearing that Mr. Patel or Mr. Bongino will retaliate for conducting legitimate investigations that Mr. Trump or his supporters disliked. Top agents in about 40 percent of the field offices have either retired, been ousted or moved into different jobs, according to people familiar with the matter and an estimate by The New York Times, which began tracking the turnover once the new administration arrived.

Tonya Ugoretz, a veteran analyst who ran the directorate of intelligence, was placed on administrative leave about two weeks ago around the time it was disclosed that she played a role in pulling back a thinly sourced intelligence report from an informant in Albany, N.Y. The informant, who was new and had indirect access to information passed onto the F.B.I., claimed that China had tried to influence the outcome of the 2020 election in favor of Joseph R. Biden Jr., according to bureau documents released to Congress.

As a top official in the cyberdivision at the time, Ms. Ugoretz recalled the intelligence report before the 2020 election because the document had serious shortcomings, according to the emails released to lawmakers. Another colleague who was involved in scrutinizing the report retired from the bureau shortly after Mr. Patel was confirmed as director.

The upheaval has catapulted others into crucial leadership roles. Will Rivers was an assistant director in charge of the security division before ascending to become the bureau’s No. 3 in March. He has endeared himself to Mr. Patel and Mr. Bongino, carrying out their personnel directives.

Jake Hemme is now Mr. Patel’s deputy chief of staff for policy, a rapid rise for someone who, according to his LinkedIn page, became an agent in July 2022.

Responding to an editorial in The Times last weekend describing how he and Mr. Patel were reshaping the bureau into an enforcement arm of Mr. Trump’s agenda, Mr. Bongino pushed back. Even as he described the article as “a poorly thought out hit piece,” he acknowledged efforts “to address the dramatic personnel changes we’ve made, along with the enterprise-wide reorganization Director Patel and I have undertaken.”

Even though the courts do not typically consider polygraphs admissible, national security agencies widely use them in investigations and background checks for security clearances, among other matters.

Under Mr. Patel and Mr. Bongino, the F.B.I. has deployed the polygraph in a highly aggressive manner. Many of the employees told to take the test have seen their colleagues removed during an initial purge by the administration as others were later pushed out or demoted. In at least one instance, the bureau put an agent on administrative leave and then brought that person back to take a test, according to a person familiar with the matter.

It is among the measures that the F.B.I. has taken that some current and former officials see as vindictive and extreme, engendering distrust among colleagues who believe there is a cadre within the bureau that has embraced snitching.

Michael Feinberg, a top agent in the field office in Norfolk, Va., until the spring, was threatened with a polygraph over his friendship with Peter Strzok, a veteran counterintelligence official who was fired for sending text messages deriding Mr. Trump.

Mr. Strzok played a central role in the F.B.I.’s investigation into whether Trump campaign aides conspired with Russia in the 2016 presidential election and is featured on Mr. Patel’s so-called enemies list published in his book “Government Gangsters.” How bureau leadership learned about the friendship is unclear.

Mr. Feinberg, writing for the national security blog Lawfare, recounted how Dominique Evans, the new top agent in charge of the Norfolk office, told him he would be “asked to submit to a polygraph exam probing the nature of my friendship with Pete.” She was acting at the direction of Mr. Bongino, Mr. Feinberg claimed as he warned of the broader implications of favoring only loyalists.

“Under Patel and Bongino, subject matter expertise and operational competence are readily sacrificed for ideological purity and the ceaseless politicization of the work force,” he wrote.

To keep his job, Mr. Feinberg added that he was “expected to grovel, beg forgiveness and pledge loyalty as part of the F.B.I.’s cultural revolution brought about by Patel and Bongino’s accession to the highest echelons of American law enforcement and intelligence.”

Mr. Feinberg resigned before he could take a polygraph.

Former polygraphers suggested the question asking employees whether they had said anything negative about Mr. Patel might also have been devised to be what is known as a control question. Such questions are intended to elicit certain physiological responses for the purposes of comparing a participant’s answers to other questions.

Whatever the reason behind the question, it is sowing mistrust and stoking concerns of a politicized F.B.I.

Mr. Patel has proved sensitive to his public image dating to his early days in government, threatening lawsuits against those who portrayed him in a potentially damaging light.

In June, Mr. Patel sued Frank Figliuzzi, a former senior F.B.I. official who contributes to MSNBC News, over his assertion that the director spent more time in nightclubs than in the office. The media organization retracted the claim, but Mr. Patel sued Mr. Figliuzzi, accusing him of defamation and saying that since being confirmed as F.B.I. director, he had not spent a “single minute inside of a nightclub.” Mr. Patel, who lives in Las Vegas, belongs to the Poodle Room, a members-only club at the Fontainebleau resort near his home.

The lawsuit, which asks for $75,000 in damages, is also blunt about its rationale. “Defendant fabricated this story because of his readily apparent animus toward Director Patel, his partisan desire to undermine the new leadership of the F.B.I. under President Donald J. Trump and to promote himself as someone with insider knowledge,” the filing states.

In 2019, Mr. Patel, then a staff member on the National Security Council under Mr. Trump, sued news organizations including The Times over reporting that described concerns about his involvement in policymaking regarding Ukraine. Mr. Patel ultimately dropped the suit against The Times, which named this reporter as a defendant, in August 2021.

Ultimately, former officials say, the polygraph question is odd on its face. In interviews, many former agents acknowledged having criticized previous directors, including Robert S. Mueller III, who ran the bureau for 12 years after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

Who hasn’t complained about their boss, one former F.B.I. official mused.

Adam Goldman writes about the F.B.I. and national security for The Times. He has been a journalist for more than two decades.

The post The F.B.I. Is Using Polygraphs to Test Officials’ Loyalty appeared first on New York Times.