Democrats and Republicans might not agree on much lately, but they seem to be converging on an unlikely political buzzword. Wherever you look on the political spectrum, organizers and strategists seeking to appeal to young audiences are describing their efforts as “hot.”

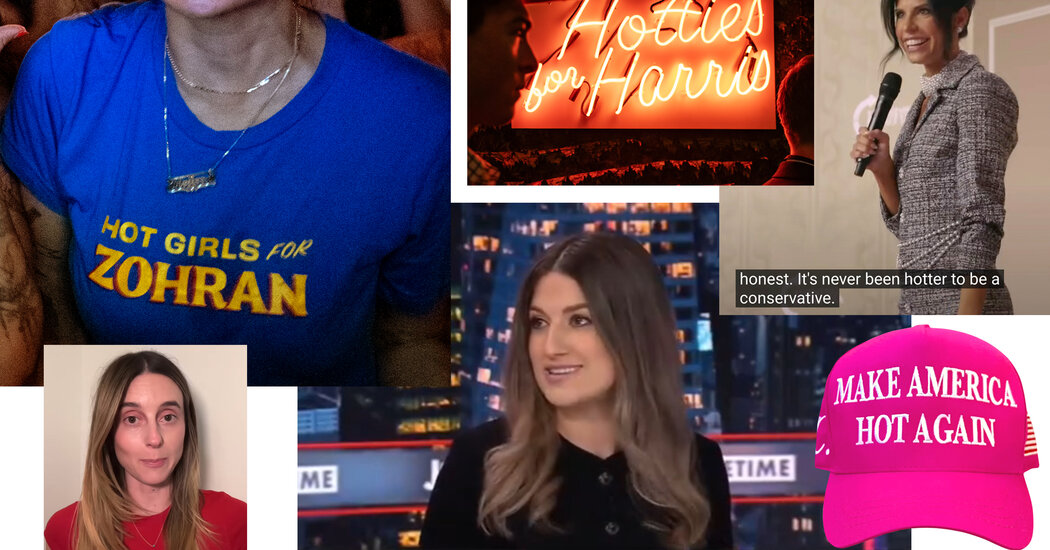

Take Hot Girls for Zohran, a group that canvassed for Zohran Mamdani in his successful Democratic primary campaign for mayor of New York, and Hotties for Harris, the name of an after-party during last year’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Or look across the aisle to the right-wing women’s lifestyle magazine The Conservateur, which sells screaming pink hats that read “Make America Hot Again.” (Lara Trump has posed in one.) Raquel Debono, who advertises her series of social mixers for conservatives with the same phrase, puts it concisely in her Instagram bio: “Hotness is a bipartisan issue.”

Injected into a political context, the word is an appealing mix of cheeky and flattering, smug and vague. We are not a party of bespectacled policy wonks, it implies; we are young, virile and fluent in the language of the internet. You should hang out with us — and maybe vote with us, too.

The word seemed to creep into the political sphere with #HotGirlsForBernie, a social media campaign that emerged during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary to show that Senator Bernie Sanders’s supporters were not just “Bernie Bros.” But it has bled across party lines, picked up by any group trying to make a case for its ideological — or literal — attractiveness.

In February, Mary Beth Barone, a comedian in Brooklyn, created a social media video series about progressive political topics after feeling discouraged by the results of the 2024 presidential election. “Politics has seemed so stuffy and ruled by these ugly old white dudes that when you put an adjective like ‘hot’ in front of something, it just makes people inherently want to be a part of it,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Barone, 34, said she chose the tongue-in-cheek name “Politics for Hot People” to draw attention to not-exactly-sexy subjects like ranked-choice voting. The way she is applying “hot” is less about looks and more about the values championed by Mr. Mamdani, her candidate of choice in the mayor’s race, she added.

“Wanting to uplift the working class in New York City and make New York City more affordable? That’s hot to me,” she said.

The word is landing differently on the right. Ms. Debono, 29, who runs the “Make America Hot Again” meet-ups for conservatives, said she chose the adjective in part because it communicated that being a Republican is “risqué” in a blue city like New York. The word also signals a disregard for political correctness that is part of the right’s appeal, she added.

“You actually can say when people are good-looking now,” Ms. Debono said.

She agrees that the word’s current usage has to do with more than just physical appearance (though, to be clear, many of the people leaning into the term happen to be women who conform to conventional standards of attractiveness). When she saw the model Emily Ratajkowski pose in a “Hot Girls for Zohran” T-shirt on social media, she thought it was a savvy play for young voters. “She’s a universal hot person,” Ms. Debono said, adding: “We’re in a looks-obsessed generation, whether we admit it or not.”

The word has undergone something of a transformation since Paris Hilton made “That’s hot” her catchphrase in the early 2000s. The rapper Megan Thee Stallion’s declaration of a “Hot Girl Summer” in 2019 inspired fans to repurpose the word for their own confidence-boosting activities.

Soon, like plenty of terms used ironically online, it evolved into a branding template for marketers of all kinds, said Amanda Montell, a linguistics writer and the author of “Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language.” “We’re just seeing it everywhere, to the point that it is kind of meaningless,” she said.

It’s logical for political messengers courting Gen Z to package age-old issues in the language of the 2020s, said Annie Wu Henry, a digital strategist who works with progressive campaigns. She pointed to the label that organizers used to describe Hollywood strikes in 2023: “Hot Labor Summer.”

But a buzzword alone is not going to sway young voters if they do not connect with a candidate or platform. The 2024 presidential election made it clear that “vibes aren’t votes,” Ms. Henry said. In that race, online excitement around Vice President Kamala Harris’s candidacy failed to deliver her the White House.

Maybe it is no coincidence that this “hot” talk is cresting at a time when beauty norms, and the beliefs they signal, are a subject of fierce interparty debate. Conservatives like the wellness influencer Alex Clark espouse “less feminism, more femininity,” while women on the left have taken part in a “Republican makeup” trend in which they mock the beauty routines of the right.

President Trump routinely comments on the physical attractiveness of his allies and opponents. (“I’m a better-looking person than Kamala,” he said during a campaign rally in Pennsylvania last year.) On Thursday morning, Mr. Trump invoked hotness in relation to the progress of his domestic policy bill.

“What a great night it was,” he wrote on Truth Social. “One of the most consequential Bills ever. The USA is the ‘HOTTEST’ Country in the World, by far!!!”

Jayme Franklin, 27, the chief executive of The Conservateur, said the magazine was founded as a rejoinder to women’s media that had embraced progressive ideas — including those about appearance. “They promote a lot of things that are not traditionally beautiful,” she said, naming tattoos, piercings and blue hair.

She thinks the “Make America Hot Again” hats have taken off because they pair a cheeky, Gen Z-approved phrase with a deeper meaning about “preserving that traditional beauty standard and owning our femininity.”

She said it did not surprise her that the same word was being used to appeal to young people with vastly different priorities. “Obviously, everybody wants to be hot,” she said.

Callie Holtermann reports on style and pop culture for The Times.

The post How ‘Hot’ Became a Bipartisan Political Buzzword appeared first on New York Times.