Photo-illustrations by Mike McQuade

In the summer of 1974, Richard Nixon was under great strain and drinking too much. During a White House meeting with two members of Congress, he argued that impeaching a president because of “a little burglary” at the Democrats’ campaign headquarters was ridiculous. “I can go in my office and pick up the telephone, and in 25 minutes, millions of people will be dead,” Nixon said, according to one congressman, Charles Rose of North Carolina.

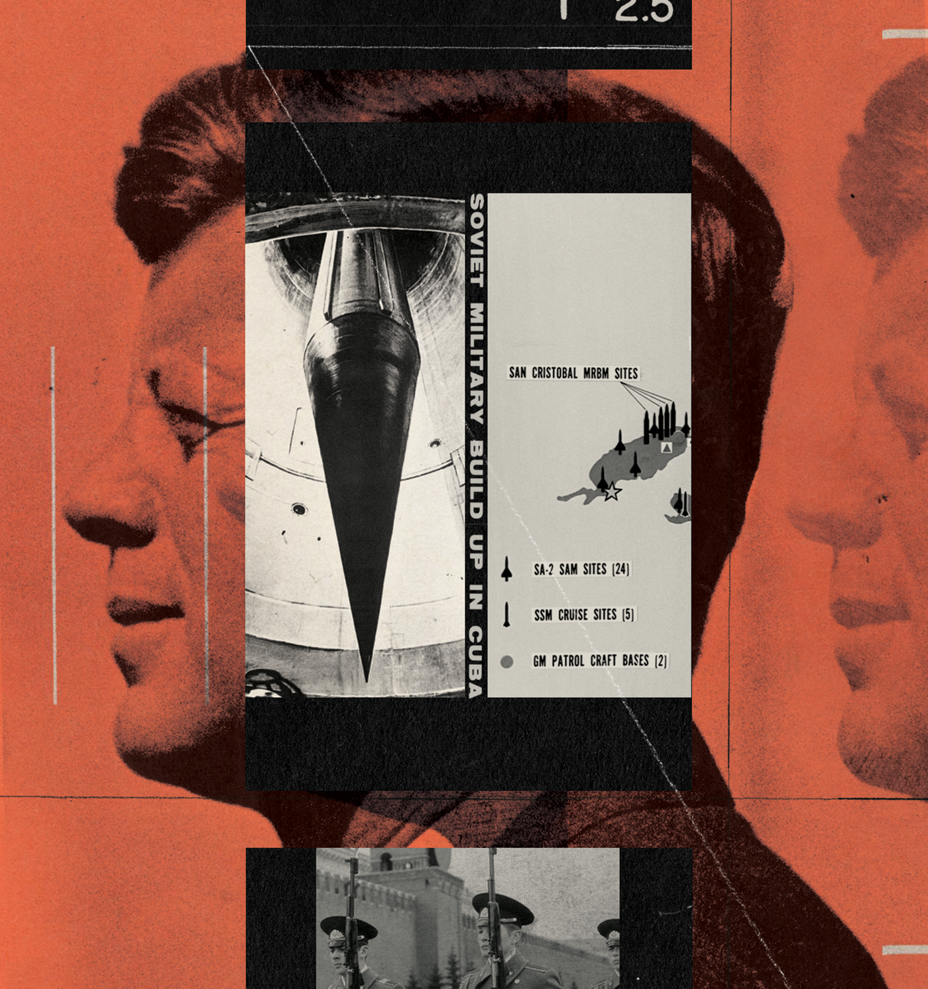

The 37th president was likely trying to convey the immense burden of the presidency, not issue a direct threat, but he had already made perceived irrationality—his “madman theory”—part of U.S. foreign policy. He had deployed B-52s armed with nuclear bombs over the Arctic to spook the Soviets. He had urged Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser, to “think big” by considering nuclear targets in Vietnam. Then, as his presidency disintegrated, Nixon sank into an angry paranoia. Yet until the moment he resigned, nuclear “command and control”—the complex but delicate system that allows a president to launch weapons that could wipe out cities and kill billions of people—remained in Nixon’s restless hands alone, just as it had for his four post–World War II predecessors, and would for his successors.

For 80 years, the president of the United States has remained the sole authority who can order the use of American nuclear weapons. If the commander in chief wishes to launch a sudden, unprovoked strike, or escalate a conventional conflict, or retaliate against a single nuclear aggression with all-out nuclear war, the choice is his and his alone. The order cannot be countermanded by anyone in the government or the military. His power is so absolute that nuclear arms for decades have been referred to in the defense community as “the president’s weapon.”

Nearly every president has had moments of personal instability and perhaps impaired judgment, however brief. Dwight Eisenhower was hospitalized for a heart attack, which triggered a national debate over his fitness for office and reelection. John F. Kennedy was secretly taking powerful drugs for Addison’s disease, whose symptoms can include extreme fatigue and erratic moods. Ronald Reagan and Joe Biden, in their later years, wrestled with the debilitations of advanced age. And at this very moment, a small plastic card of top-secret codes—the president’s personal key to America’s nuclear arsenal—is resting in one of President Donald Trump’s pockets as he fixates on shows of dominance, fumes about enemies (real and perceived), and allows misinformation to sway his decision making—all while regional wars simmer around the world.

For nearly 30 years after the Cold War, fears of nuclear war seemed to recede. Then relations with Russia froze over and Trump entered politics. Voters handed him the nuclear codes—not once, but twice—even though he has spoken about unleashing “fire and fury” against another nuclear power, and reportedly called for a nearly tenfold increase in the American arsenal after previously asking an adviser why the United States had nuclear weapons if it couldn’t use them. The Russians have repeatedly made noise about going nuclear in their war against Ukraine, on the border of four NATO allies. India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers, renewed violent skirmishes over Kashmir in May. North Korea plans to improve and expand its nuclear forces, which would threaten U.S. cities and further agitate South Korea, where some leaders are debating whether to develop the bomb for themselves. And in June, Israel and the United States launched attacks against Iran after Israel announced its determination to end—once and for all—Iran’s nascent nuclear threat to its existence.

If any of these conflicts erupts, the nuclear option rests on command and control, which hinges on the authority—and humanity—of the president. This has been the system since the end of World War II. Does it still make sense today?

Here’s how the end of the world could begin. Whether the president is directing a first strike on an enemy, or responding to an attack on the United States or its allies, the process is the same: He would first confer with his top civilian and military advisers. If he reached a decision to order the use of nuclear weapons, the president would call for “the football,” a leather-bound aluminum case that weighs about 45 pounds. It is carried by a military aide who is never far from the commander in chief no matter where he goes; in many photos of presidents traveling, you can see the aide carrying the case in the background.

There is no nuclear “button” inside this case, or any other way for the president to personally launch weapons. It is a communications device, meant to quickly and reliably link the commander in chief to the Pentagon. It also contains attack options, laid out on laminated plastic sheets. (These look like a Denny’s menu, according to those who have seen them.) The options are broadly divided by the size of the strikes. The target sets are classified, but those who work with nuclear weapons have long joked that they could be categorized as “Rare,” “Medium,” and “Well-Done.”

Once the president has made his choices, the football connects him to an officer in the Pentagon, who would immediately issue a challenge code using the military phonetic alphabet, such as “Tango Delta.” To verify the order, the president must read the corresponding code from the plastic card (nicknamed “the biscuit”) in his pocket. He needs no other permission; however, another official in the room, likely the secretary of defense, must affirm that the person who used the code is, in fact, the president.

The Pentagon command center would then, within two minutes, issue specific mission orders to the nuclear units of the Air Force and Navy. Men and women in launch centers deep underground in the Great Plains—or in the cockpits of bombers on runways in North Dakota and Louisiana, or aboard submarines lurking in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans—would receive target packages, codes, and orders to proceed with the use of their nuclear weapons.

If enemy missiles are inbound, this process would be crammed into a matter of minutes, or seconds. Nuclear weapons launched from Russian submarines in the Atlantic could hit the White House only seven or eight minutes after a launch is detected. Confirmation of the launch could take five to seven minutes, as officials scramble to rule out a technical error.

Errors have happened, multiple times, in both the United States and Russia. In June 1980, President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, received a call from his military aide in the middle of the night, according to Edward Luce’s new biography of Brzezinski. The aide told Brzezinski that hundreds—no, thousands—of Soviet missiles were inbound, and he should prepare to wake the president. As he waited for the military to confirm the attack, Brzezinski decided not to wake his wife, thinking that she was better off dying in her sleep than knowing what was about to happen.

The aide called back. False alarm. Someone had accidentally fed a training simulation into the NORAD computers.

In an actual attack, there would be almost no time for deliberation. There would be time only for the president to have confidence in the system, and make a snap decision about the fate of the Earth.

The destruction of Hiroshima changed the character of war. Battles might still be fought with conventional bombs and artillery, but now whole nations could be wiped out suddenly by nuclear weapons. World leaders intuited that nuclear weapons were not just another tool to be wielded by military commanders. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said to U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson in 1945: “What was gunpowder? Trivial. What was electricity? Meaningless. This atomic bomb is the Second Coming in Wrath.”

Harry Truman agreed. He never doubted the need to use atomic bombs against Japan, but he moved quickly to take control of these weapons from the military. The day after the bombing of Nagasaki, Truman declared that no other nuclear bombs be used without his direct orders—a change from his permissive “noninterference” in atomic matters until that point, as Major General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, later described it. As a third bomb was readied for use against Japan, Truman established direct, personal control over the arsenal. Truman didn’t like the idea of killing “all those kids,” Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace wrote in his diary on August 10, 1945, adding that the president believed that “wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible” to contemplate.

In 1946, Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act, placing the development and manufacture of nuclear weapons firmly under civilian control. Two years later, a then-top-secret National Security Council document stated clearly who was in charge: “The decision as to the employment of atomic weapons in the event of war is to be made by the Chief Executive.”

Military eagerness to use atomic weapons was not an idle concern. When the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb, in 1949, some military officials urged Truman to act first and destroy the Soviet nuclear program. “We’re at war, damn it!” Major General Orvil Anderson said. “Give me the order to do it, and I can break up Russia’s five A-bomb nests in a week! And when I went up to Christ, I think I could explain to him why I wanted to do it—now—before it’s too late. I think I could explain to him that I had saved civilization!” The Air Force quickly relieved Anderson, but the general wasn’t alone. Influential voices in American political, intellectual, and military circles were in favor of preventive nuclear attack against the Soviet Union. But only the president’s voice mattered.

Truman took power over the bomb to limit its use. But as command and control morphed to accommodate more advanced weapons and the rising Soviet threat, the president needed to be able to order a variety of nuclear strikes against a variety of targets. And he could launch any of them without so much as a courtesy call to Congress (let alone waiting for its declaration of war). Should he want to, the president could, in effect, go to war by himself, with his weapon.

In the early 1950s, the United States created a primitive nuclear strategy, aimed at containing the Soviet Union. America and its allies couldn’t be everywhere at once, but they could make the Kremlin pay the ultimate price for almost any kind of mischief in the world, not just a nuclear attack on the United States. This idea was called “massive retaliation”: a promise to use America’s “great capacity to retaliate, instantly, by means and at places of our choosing,” in the words of Eisenhower’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles.

When the Soviets launched Sputnik into space in October 1957, Eisenhower’s approval rating had already been dropping for months, and he signed off on a major arms buildup, allowing for more targets—even though he remained deeply skeptical about the utility of nuclear weapons. “You can’t have this kind of war,” he said at a White House meeting a month after Sputnik. “There just aren’t enough bulldozers to scrape the bodies off the streets.”

Ike’s successors would likewise remain suspicious of the nuclear option, even as the U.S. military relied on their willingness to invest in it. And the system was getting trickier to manage: As the power of the arsenal increased, so did the possibilities for misunderstanding and miscalculation.

In 1959, the bomber era gave way to the missile era, which likewise complicated nuclear decision making. Intercontinental ballistic missiles streaking around the globe at many times the speed of sound were more frightening than Soviet bombers sneaking over the Arctic. Suddenly, the president’s window to make grave decisions shrank from hours to minutes, rendering broader deliberations impossible and bolstering the need for only one person to have nuclear authority.

At about the same time, the Soviets were surrounding U.S., French, and British forces in Berlin, putting East and West in direct confrontation—making nuclear war more likely, and compounding the strain on the president. If the West refused to back down in any provincial conflict elsewhere in the world, the Soviets could move into West Germany, betting that doing so would collapse NATO and make Washington capitulate. The Americans, in turn, were betting that the threat (or use) of nuclear weapons would prevent (or halt) such an invasion.

But if either side crossed the nuclear threshold on the European battlefield, the game would soon come down to: Which superpower is going to launch an all-out attack on the other’s homeland first, and when?

In such nuclear brinkmanship, every decision made by the president could spark a catastrophe. If he stayed in Washington, he would risk being killed. If he evacuated the White House, the Soviets could take it as a sign that the Americans were readying a strike—which in turn could provoke their fears, and move them to strike first. In the midst of this frenzy, billions of lives and the future of civilization would depend on the perceptions and emotions of the American president and his opponents in the Kremlin.

Presidents decide, but planners plan, and what planners do is find targets for ordnance. In late 1960, just before Kennedy entered the White House, the U.S. military developed its first set of options meant to coordinate all nuclear forces in the event of a nuclear war. It was called the Single Integrated Operational Plan, or SIOP, but it wasn’t much of a plan.

The 1961 SIOP envisioned throwing everything in the U.S. arsenal not only at the Soviet Union but at China as well, even if it wasn’t involved in the conflict. This was not an option so much as an order to kill at least 400 million people, no matter how the war began. Kennedy was told bluntly (and correctly) by his military advisers that even after such a gargantuan strike, some portion of the Soviet arsenal was nonetheless certain to survive—and inflict horrifying damage on North America. Mutual assured destruction, as it would soon be called. At a briefing on the SIOP hosted by General Thomas Power, a voice of reason spoke up, according to a defense official, John Rubel:

“What if this isn’t China’s war?” the voice asked. “What if this is just a war with the Soviets? Can you change the plan?”

“Well, yeah,” said General Power resignedly, “we can, but I hope nobody thinks of it, because it would really screw up the plan.”

Power added: “I just hope none of you have any relatives in Albania,” because the plan also included nuking a Soviet installation in the tiny Communist nation. The commandant of the Marine Corps, General David Shoup, was among those disgusted by the plan, saying that it was “not the American way,” and Rubel would later write that he felt like he was witnessing Nazi officials coordinating mass extermination.

Every president since Eisenhower has been aghast at his nuclear options. Even Nixon was shocked by the level of casualties envisioned by the latest SIOP. In 1974, he ordered the Pentagon to develop options for the “limited” use of nuclear weapons. When Kissinger asked for a plan to stop a notional Soviet invasion of Iran, the military suggested using nearly 200 nuclear bombs along the Soviet-Iranian border. “Are you out of your minds?” Kissinger screamed during a meeting. “This is a limited option?”

In late 1983, Ronald Reagan received a briefing on the latest SIOP, and he wrote in his memoir that “there were still some people at the Pentagon who claimed a nuclear war was ‘winnable.’ I thought they were crazy.” The Reagan adviser Paul Nitze, shortly before his death, told a fellow ambassador: “You know, I advised Reagan that we should never use nuclear weapons. In fact, I told him that they should not be used even, and especially, in retaliation.”

By the end of the Cold War, the system—though commanded by the president—had metastasized into something nearly uncontrollable: a highly technical cataclysm generator, built to turn unthinkable options into devastating actions. Every president was boxed in: a single command, basically, and very little control. In 1991, George H. W. Bush began to hack away at the overgrown system by presiding over major cuts in American weapons and the number of nuclear targets. But presidents come and go, and war planners remain: The military increased the target list by 20 percent in the years after Bush left office.

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has undertaken some meaningful reforms, including negotiating major reductions in U.S. and Russian nuclear inventories, and creating more safeguards against technical failures. In the ’90s, for example, American ballistic missiles were targeted at the open ocean, in case of accidental launch. If a nuclear crisis erupts, though, the president will still be presented with plans and options that he didn’t design or even desire.

In 2003, the SIOP was replaced by a modern operations plan (OPLAN) that ostensibly gives the president more options than the extinction of humanity, including delayed responses rather than instant retaliation. But that initial OPLAN also reportedly included options to devastate small, nonnuclear nations, and although the details are secret, military exercises and unclassified documents over the past 20 years indicate that modern nuclear plans largely seem imported from the previous century.

The concentration of power in the presidency, the compression of his decision timeline, and the methodical targeting done by military planners have all conspired, over 80 years, to produce a system that carries great and unnecessary risks—and still leaves the president free to order a nuclear strike for any reason he sees fit. There are ways, though, to reduce that risk without undermining the basic strategy of nuclear deterrence.

The first thing the United States could do—to limit an impetuous president, and reduce the likelihood of doomsday—is commit to a policy of “no first use” of nuclear weapons. A law to prohibit a first strike without congressional approval was reintroduced in the House of Representatives earlier this year, though it is unlikely to pass. Absent congressional action, any president could commit to no first use by executive order, which might create breathing room during a crisis (if adversaries believe him, that is).

And every president should insist that the options available in the face of an incoming strike include more limited retaliatory strikes, and fewer all-out responses. In other words: Delete the items we don’t need from the Denny’s menu, and reduce the existing portions. America may need only a few hundred deployed strategic warheads—rather than the current 1,500 or so—to maintain deterrence. Even at that lower number, no nation has enough firepower to strip away all American retaliatory capabilities with a first strike. A president who orders a reduction in the number of deployed warheads, while still holding key targets at risk, would wrest back some control over the system, just as a functioning Congress could pass legislation to limit the president’s nuclear options. The world would be safer.

Of course, none of this solves the fundamental nuclear dilemma: Human survival depends on an imperfect system working perfectly. Command and control relies on technology that must always function and heads that must always stay cool. Some defense analysts wonder if AI—which reacts faster and more dispassionately to information than human beings—could alleviate some of the burden of nuclear decision making. This is a spectacularly dangerous idea. AI might be helpful in rapidly sorting data, and in distinguishing a real attack from an error, but it is not infallible. The president doesn’t need instantaneous decisions from an algorithm.

Vesting sole authority in the president is perhaps the least worst option when it comes to deterring a major attack. In a time crunch, groupthink can be as dangerous as the frenzied judgment of one person, and retaliatory orders must remain the president’s decision—above any bureaucracy, and separate from the military and its war games. The choice to strike first, however, should be a political debate. The president should not have the option to start a nuclear war by himself.

But what happens when a president with poor judgment or few morals arrives in the White House, or when a president deteriorates in office? Today, the only immediate checks on a reckless president are the human beings in the chain of command, who would have to choose to abdicate their duties in order to stall or thwart an order they found reprehensible or insane. Members of the military, however, are trained to obey and execute; mutiny is not a fail-safe device. The president could fire and replace anyone who impedes the process. And U.S. service members should never be put in a position to stop orders that defy reason; gaming out such a scenario is corrosive to national security and American democracy itself.

When I asked a former Air Force missile-squadron commander if senior officers could refuse the order to launch nuclear weapons, he said: “We were told we can refuse illegal and immoral orders.” He paused. “But no one ever told us what immoral means.”

In the end, the American voters are a kind of fail-safe themselves. They decide who sits at the top of the system of command and control. When they walk into a voting booth, they should of course think about health care, the price of eggs, and how much it costs to fill their gas tank. But they must also remember that they are in fact putting the nuclear codes in the pocket of one person. Voters must elect presidents who can think clearly in a crisis and broadly about long-term strategy. They must elevate leaders of sound judgment and strong character.

The president’s most important job, as the sole steward of America’s nuclear arsenal, is to prevent nuclear war. And a voter’s most important job is to choose the right person for that responsibility.

This article appears in the August 2025 print edition with the headline “The President’s Weapon.”

The post The President’s Weapon appeared first on The Atlantic.